CNN

—

A goalkeeper from southern California. A defender from Seattle. A forward from Washington DC.

These are just a few players on the Philippines’ team at this year’s Women’s World Cup – where 18 of the country’s 23-member squad were born in the United States.

And it’s not just the Philippines. Despite the early exit of the US team on Sunday, the influence the country has on other competing nations is clear, with dozens of players born or raised in America representing other teams including Haiti, Jamaica and more.

It’s a reflection of the global nature of the sport, with dual-nationality athletes increasingly hopping across borders to seek better career opportunities, or to connect with parts of their heritage.

But while US-born women soccer players have flowed outward, populating other countries’ teams, the opposite trend has been seen in the US men’s team, with an influx of athletes born or raised overseas.

At the men’s World Cup last year, the US team featured several prominent players with overseas ties, including Fulham defender Antonee Robinson, who was born in the United Kingdom; Netherlands-born Sergiño Dest, who plays for FC Barcelona; and – perhaps most notably – US-born forward Tim Weah, whose father – legendary former striker George Weah – captained Liberia before becoming the West African country’s President.

There are various factors behind this trend, experts say – but it mostly boils down to a massive gap in talent and performance between the US men’s and women’s teams.

The US women’s team has been historically dominant, winning four World Cups (and four Olympic gold medals). In contrast, since reaching the World Cup semi-finals at the inaugural tournament in 1930, the US men’s team have reached the quarter-finals just once and have never been serious contenders for the title.

This stark difference in performance means there’s an “inverse (path) of migration and citizenship options,” said Gijsbert Oonk, director of the Sport and Nation research program at Erasmus University Rotterdam, which focuses on the role of citizenship and migration within football and the Olympic Games.

The civil rights law Title IX, passed in 1972, is one major reason why the US women’s team is so strong, experts say.

The law, which prohibits sex discrimination at federally funded schools, meant if colleges offered scholarships to male athletes they would have to offer them to female athletes too. Soccer became a pathway to higher education, consequently increasing participation in the game and pushing colleges to invest huge amounts of money in women’s programs.

“In a vacuum where there were practically no resources for women’s sports, Title IX was a game-changer for American female athletes. And since the rest of the world didn’t invest in women’s sports either, it gave the [US women’s team] a huge advantage,” said Leander Schaerlaeckens, a senior lecturer in sports communication at Marist College.

The US was also ahead of the curve – Title IX became federal law a year after a ban on women’s soccer was lifted in England, the country where the modern sport began. In Brazil, a giant of the men’s game, it was still illegal for women to play soccer.

While the rest of the world was changing its attitude towards women’s soccer at a snail’s pace, Title IX gave the US a head start.

By the time the world’s traditional soccer powerhouses had started to invest in women’s soccer, which is only relatively recently, the well-oiled wheels of the US production line had been churning out female athletic talent for decades.

But the men’s team has long lagged behind their global peers for a host of reasons that are also, in many ways, unique to the United States.

International rivals have long established robust youth development programs, making a far tougher playing field.

And for American men, college actually hindered their professional soccer careers, “since talented teenaged boys in Spain or England or Argentina or wherever were hopping straight from academies into the pros, without needing to go play in college first,” Schaerlaeckens said.

There were cultural social factors, too.

For decades, the top sports for American boys were baseball, American football, and basketball – with soccer often viewed as “not a real man’s sport,” said Oonk, the Erasmus University director. It’s an “entirely different picture” in much of Europe and Latin America where soccer is by far the most popular sport.

The best photos of the 2023 Women’s World Cup

The dominance of the US women’s team and quality of the country’s female soccer development means there are more talented players than the national squad can take – and players who don’t make the cut may then look elsewhere.

“If you are born and raised in the US and you hold dual citizenship, for example Nigerian or Jamaican or Mexican, and you are an excellent football player but you won’t make it to the US national team … you have the option to represent … any other country,” said Oonk.

Even if they’re good enough to make the women’s side, they may not be selected for the 23-player World Cup roster, or may only play a bit-part from the substitutes’ bench. In that case, it may still be a better option for an American player to move to another national team where they can shine, he added.

Schaerlaeckens added that the abundance of American women’s talent represented a “valuable commodity to be mined” – meaning “those leftover players tend to have no shortage of suitors among the nations they might be eligible for.”

The opposite is true of the men’s side.

“Absent enough talent of its own, the men’s national team has found opportunity in a changing environment that allows players to switch nations,” said Schaerlaeckens.

“At first, they went after the dual-national players who plainly had no chance of making another country’s national team. More recently, it has also pursued those also coveted by the nations of their birth, or where they were primarily developed.”

Some female players have alluded to these motivations, such as Sarina Bolden, a California-born player with the Philippines’ World Cup squad.

“Essentially it kind of boiled down to being able to make an impact,” she told CNN. “The US is highly, highly competitive, it’s a big country so there’s a lot of talent to pull from … When am I going to have the opportunity to even play in a World Cup?”

Many women players also cite their personal heritage as major factors in representing another country.

Under FIFA’s rules, players can only represent countries where they hold nationality, such as their countries of birth or those where their parents or grandparents are from. They can also represent nations with no link to ancestry if they have lived there for a certain number of years.

That means many US-born players overseas are representing their families’ homelands – which many cite as a powerful connection.

Until Bolden joined the Philippines team, she’d never even visited the Southeast Asian country, she said, adding she had wanted to “explore more of the other side of me, my roots.”

Noa Ganthier, a 20-year-old from Florida, said the first time she attended a soccer camp in her father’s native Haiti, she felt something click in a way she’d never experienced at similar sessions in the US.

“I was singing and dancing the first time, we’re all laughing, having fun together. It was just a completely different vibe,” she said. “From that moment I knew for sure (I wanted to play for Haiti).”

She represented Haiti at the World Cup, where they made their debut this year before being knocked out in the qualifying rounds.

“There’s a different pride playing for Haiti,” she said. “I can’t describe the feeling but putting the jersey on, seeing your last name on a Haitian jersey, is one of the best feelings I’ve ever had.”

Danielle Etienne, a Virginia native also on the Haitian women’s team, said Haiti was the country that “saw me for me, and saw me as someone of value.” Her father, Derrick Etienne, played for Haiti’s men’s national team.

“Being American, that’s where I was born – but I’m Haitian through and through,” she said.

Though the proportion of foreign-born players on international soccer teams has remained fairly stable for decades – 10-12% on men’s teams, and 6-8% on women’s, according to Oonk’s research – it could grow rapidly in the years ahead, he said.

“There are more countries active now … in finding dual nationals abroad that may represent their countries,” he said, pointing to Mexico and Nigeria’s women’s teams.

Many African nations are also looking for potential athletes in the African diaspora, for both men’s and women’s soccer, he added. The same trend has been seen in Asia, with China and Vietnam among those recruiting athletes who were born or raised overseas – even if they don’t speak the language or have never stepped foot in their ancestral countries.

The practice has also courted controversy, specifically regarding athletes who play for countries they have no ancestral ties to.

For example, Brazil-born player Elkeson was naturalized as a Chinese citizen in 2019 and selected for the men’s national squad ahead of its World Cup qualifiers, after fulfilling FIFA’s residency rules. It was the first time a player with no Chinese heritage had been selected for the national team in a country that historically has very little immigration.

Instances like these raise a moral quandary for the sporting world, with some questioning the value of international sports events when teams can shop for non-nationals, Oonk said.

Others point out that allowing players to choose whichever team offers the best opportunities or pay, regardless of nationality, lends an unfair advantage to wealthy nations hungry for global recognition – and could take opportunities away from athletes in those countries.

To this end, national sports federations have tried to impose certain regulations to make it more difficult for athletes to jump around. But, experts say, teams will inevitably become more diverse as multiple nationalities become more common.

“I think international soccer has, for some time, and both on the men’s and women’s side, been a kind of microcosm for globalization,” Schaerlaeckens said.

“A great many players are now eligible to represent two or three or more countries. This is the way of the world now, and soccer has reflected that.”

Australia won 2-0 to advance to the quarterfinals.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1869″ width=”2803″/>

Australia won 2-0 to advance to the quarterfinals.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1869″ width=”2803″/>

The match went to a shootout after ending 0-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2462″ width=”3498″ loading=’lazy’/>

The match went to a shootout after ending 0-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2462″ width=”3498″ loading=’lazy’/>

being eliminated by Sweden in a penalty shootout on Sunday, August 6. The United States won the last two tournaments.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2641″ width=”3962″ loading=’lazy’/>

being eliminated by Sweden in a penalty shootout on Sunday, August 6. The United States won the last two tournaments.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2641″ width=”3962″ loading=’lazy’/>

The two teams drew 0-0, but it was Jamaica that advanced to the knockout stage of the tournament. This was the last World Cup for Marta, the tournament’s record scorer and veteran of six tournaments.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1334″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

The two teams drew 0-0, but it was Jamaica that advanced to the knockout stage of the tournament. This was the last World Cup for Marta, the tournament’s record scorer and veteran of six tournaments.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1334″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

3-2 win over Italy on August 2. It was South Africa’s first-ever win at a Women’s World Cup, and it helped them clinch a spot in the next round. Italy was eliminated with the loss.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1333″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

3-2 win over Italy on August 2. It was South Africa’s first-ever win at a Women’s World Cup, and it helped them clinch a spot in the next round. Italy was eliminated with the loss.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1333″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Sweden won 2-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1333″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Sweden won 2-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1333″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

England won 6-1 to advance to the tournament’s round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

England won 6-1 to advance to the tournament’s round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

The win, coupled with China’s defeat against England, meant Denmark would advance to the knockout stage and face co-host Australia.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

The win, coupled with China’s defeat against England, meant Denmark would advance to the knockout stage and face co-host Australia.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

goalless draw against Portugal on August 1. The result meant that the Americans, the two-time defending champions, would advance to the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

goalless draw against Portugal on August 1. The result meant that the Americans, the two-time defending champions, would advance to the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Australia won 4-0 to book a spot in the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1731″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Australia won 4-0 to book a spot in the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1731″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

4-0 victory over Spain on July 31. Both teams are advancing to the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

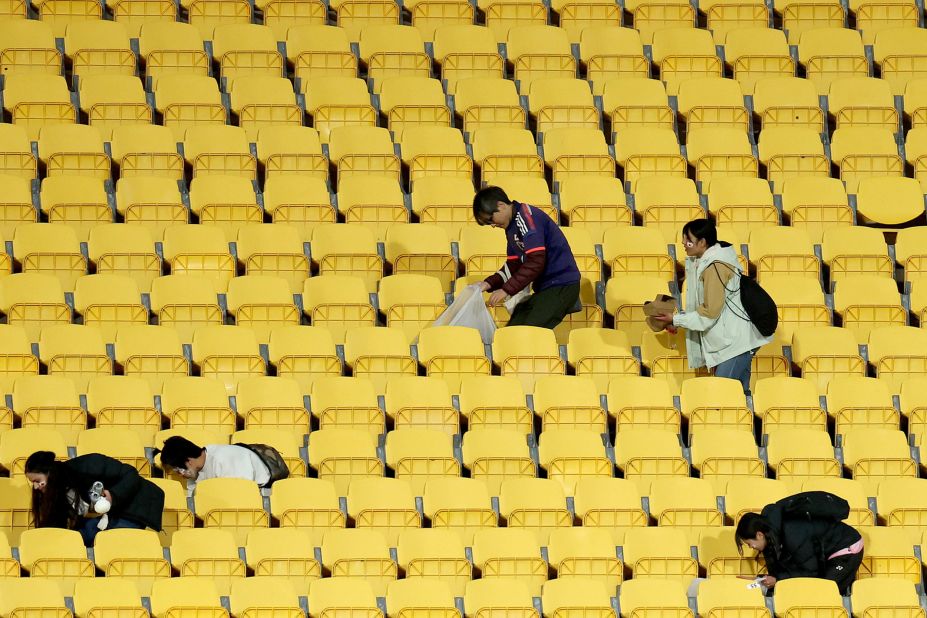

4-0 victory over Spain on July 31. Both teams are advancing to the round of 16.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/> clean stands after matches.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

clean stands after matches.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1667″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

2-1 victory.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

2-1 victory.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

the first player to wear a hijab at a World Cup, is shown a yellow card by referee Edina Alves Batista. ” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1110″ width=”1600″ loading=’lazy’/>

the first player to wear a hijab at a World Cup, is shown a yellow card by referee Edina Alves Batista. ” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1110″ width=”1600″ loading=’lazy’/>

Jamaica won 1-0. It was Jamaica’s first-ever win at a Women’s World Cup.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1928″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Jamaica won 1-0. It was Jamaica’s first-ever win at a Women’s World Cup.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1928″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

2-1 win against Brazil on July 29.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

2-1 win against Brazil on July 29.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

China won 1-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

China won 1-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

England won 1-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2035″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

England won 1-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2035″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

received criticism for her Cristiano Ronaldo tattoo, the rival of Argentina star Lionel Messi.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1334″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

received criticism for her Cristiano Ronaldo tattoo, the rival of Argentina star Lionel Messi.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1334″ width=”2000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Nigeria defeated Australia 3-2 on July 27. The stunning result means Nigeria has a one-point lead going into its final group game against already eliminated Ireland, while co-host Australia faces a must-win match against Canada.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Nigeria defeated Australia 3-2 on July 27. The stunning result means Nigeria has a one-point lead going into its final group game against already eliminated Ireland, while co-host Australia faces a must-win match against Canada.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Canada won 2-1.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Canada won 2-1.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

lifted her country to a 1-0 victory — its first win ever at a Women’s World Cup.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2028″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

lifted her country to a 1-0 victory — its first win ever at a Women’s World Cup.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2028″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Brazil won 4-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Brazil won 4-0.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Germany dominated Morocco 6-0 in what was the biggest scoreline of the tournament so far.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

Germany dominated Morocco 6-0 in what was the biggest scoreline of the tournament so far.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

youngest player to represent Italy in the competition’s history. ” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

youngest player to represent Italy in the competition’s history. ” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”2000″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

single-game attendance record for a women’s soccer match in Australia, with 75,784 fans watching.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1909″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

single-game attendance record for a women’s soccer match in Australia, with 75,784 fans watching.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1909″ width=”3000″ loading=’lazy’/>

The roughly 10-minute opening ceremony celebrated both New Zealand and Australia’s indigenous heritage and culture, with Māori and First Nations dancers and singers taking to the center of the field.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1548″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>

The roughly 10-minute opening ceremony celebrated both New Zealand and Australia’s indigenous heritage and culture, with Māori and First Nations dancers and singers taking to the center of the field.” class=”image__dam-img image__dam-img–loading” onload=’this.classList.remove(‘image__dam-img–loading’)’ onerror=”imageLoadError(this)” height=”1548″ width=”2500″ loading=’lazy’/>