When asked how important in the history of music is Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford replied, “It’s immensely important. It’s literally and metaphorically bigger than any other symphony – that’s what it’s intended to be. It’s Beethoven’s hug for the whole world.”

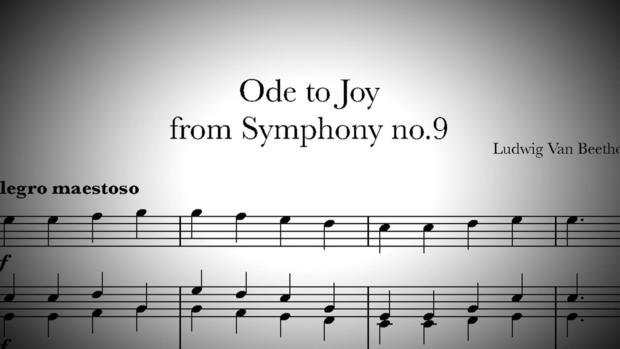

And, said Swafford, it’s no coincidence that the symphony’s final movement, the triumphal “Ode to Joy,” has long been a worldwide anthem of freedom and peace.

“Beethoven wanted to write an anthem for humanity with this little tune that anybody can sing,” Swafford told correspondent Mo Rocca. “Probably half the population of the Earth knows that tune, whether they know it’s by Beethoven or not.”

Mariner Books

The Ninth was Beethoven’s final major work, the coda to an epic life in music.

Conductor Marin Alsop said, “It’s impossible to actually think about the history of music, the history of humanity, without Beethoven.”

Last year the pandemic complicated plans to celebrate Beethoven’s 250th birthday. But, said Alsop, there may be no better time to reflect on the man and his philosophy: “It’s about coming to terms with tremendous challenge, strife, struggle, and deciding that it’s worth it,” she said.

Strife and struggle were constants in the composer’s life. Born in 1770 in the German city of Bonn, Ludwig van Beethoven was by age ten considered the next Mozart. But throughout his life he was plagued with physical maladies.

“He may have had chronic lead poisoning,” Swafford said. “He had colitis. He had fevers and headaches that lasted for months.”

Even worse, in his late 20s the composer began to lose his hearing. “He wrote this letter, which is partly a suicide note and partly a statement of defiance – it’s both – he just said in this letter, ‘I’m gonna be the most miserable person in the world,'” Swafford laughed. “‘But I’m gonna live for my art’ – because I can’t imagine killing myself, basically, ‘before I’ve done what I know I can do.'”

And so, as the world around him gradually fell silent, Beethoven wrote at a furious pace: string quartets, piano compositions and, of course, symphonies. But by the 1820s, Beethoven – his health worse than ever, his personal life in shambles – was no longer writing as easily.

Rocca asked, “Was it an open question whether or not Beethoven would be back, before the Ninth premiered?”

“The general opinion about Beethoven was that he was so sick and crazy that he was finished,” Swafford said.

But Beethoven wasn’t through just yet. Passionately political all his life, he adapted the Friedrich Schiller poem “Ode to Joy” – a revolutionary call for freedom – for his symphony, a radical act.

CBS News

Swafford said, “By the time Beethoven wrote the Ninth Symphony, Vienna was a police state. And it’s amazing to me that everybody knew what the ‘Ode to Joy’ was about, it was about the revolutionary period. Beethoven was tapping into all that to keep the dream of freedom alive in a bad time.”

Of the Ninth, San Francisco-based hearing specialist Dr. Charles Limb remarked, “I think you could rightly say, and I think of this, it’s the greatest accomplishment in musical history.”

“The writing of the Ninth by a man who was essentially deaf?” asked Rocca.

“I don’t know how you could ask more of a human being.”

Limb was inspired to create simulations of how Beethoven may have heard his own compositions, with really severe hearing loss – a muddy, distorted sound that’s barely audible.

“You can tell right away there’s a loss of clarity; you’re just hearing rumblings,” said Limb. “And you can’t even tell really that it was based once on a piece of music.

“You can fairly state that he composed the Ninth Symphony using his mind’s ear.”

“What does that mean?” Rocca asked.

“If you just stop right now and try to hear the Ninth Symphony in your head, you can ‘hear’ it,” Limb replied. “And you’re hearing it because your auditory memory allows you to have that recollection.”

CBS News

Marin Alsop thinks Beethoven’s loss of hearing may very well have liberated him creatively. “I think because he didn’t hear the pieces played, he didn’t censor them in the same way,” she said. “He kept moving forward in terms of experimentation, in terms of taking risks.”

At the premiere of the Ninth Symphony, on May 7, 1824, the crowd went wild – but Beethoven couldn’t hear them.

Swafford said, “Somebody had to turn him around [so he could] see the audience going crazy. But it wasn’t for the music; it was for him.”

Twenty-two years after he contemplated taking his own life, a determined, defiant Beethoven gave the world a reminder that, even in the darkest of times, there’s potential for joy.

For more info:

Story produced by Sara Kugel. Editor: George Pozderec.

Download our Free App

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app