Naples, Florida

CNN

—

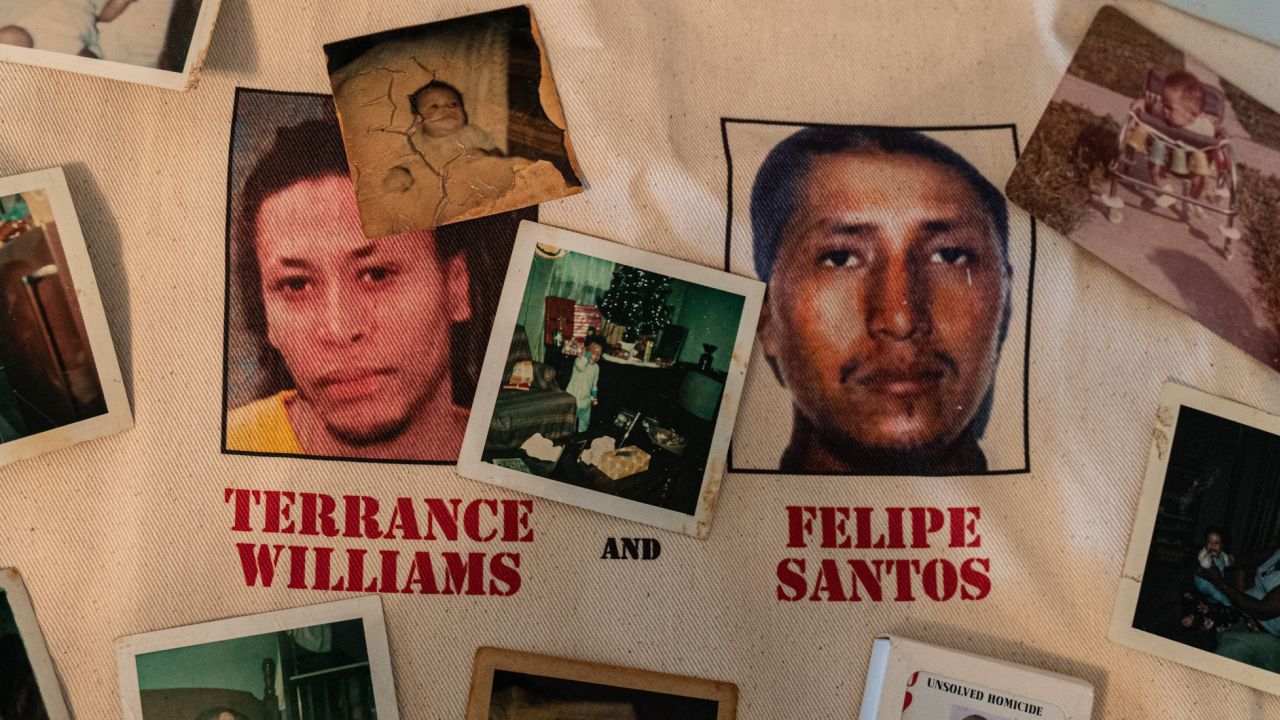

One morning 19 years ago, Marcia Williams woke up praying for her son. Terrance worked two jobs, and liked reading about Socrates, and had a scar on his right hand, near the thumb, from one time when he played with matches as a little boy. He was Marcia’s only child. She prayed and prayed, fighting against this inexplicable feeling that something terrible was about to happen.

A few hours later, Terrance crossed paths with a deputy sheriff. He got in the deputy’s patrol car. Then he disappeared.

The deputy said he’d given Terrance a ride to a Circle K convenience store. But there was no proof that Terrance arrived at the Circle K. And his mother never saw him again.

Eventually, Marcia learned something astonishing about this deputy sheriff.

Three months earlier, another man had also taken a ride in his patrol car.

Just like Terrance Williams, Felipe Santos had been driving illegally.

Just like Williams, he encountered Cpl. Steven Calkins of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office.

And just like Williams, he disappeared right after that.

The deputy said he’d dropped Santos off at a Circle K convenience store. But there was no proof that Santos arrived at the Circle K. And his family never saw him again.

Calkins is White. Santos was Latino. Williams was Black.

“It is my belief that they were killed because of their color,” said Doug Molloy, who was an assistant US attorney in 2004 and led a multi-agency task force that investigated the disappearances as potential hate crimes.

Sheriff’s investigators surveyed the evidence and determined that Calkins was not telling the truth about his encounter with Terrance Williams. One investigator made a list of nearly two dozen untruthful or inconsistent statements that Calkins made about the day he met Williams. In August 2004, about seven months after Williams disappeared, then-Sheriff Don Hunter fired Calkins. As he later wrote, “I have lost trust in Calkins and his ability to describe incidents in detail and to recall them.”

Meanwhile, investigators got to work. They searched the woods and the waters near where the missing men were last seen. They put a tracking device on Calkins’ car. They did a complete forensic inspection of the car, paying special attention to the trunk. No trace of Santos or Williams turned up.

The FBI delivered a target letter to Calkins and asked him to answer questions from a federal grand jury about the disappearances. Calkins declined. And the investigators’ suspicions did not lead to probable cause. No one could prove these were hate crimes, or even crimes at all. Years passed, and the cases remained open, and both men’s children grew up without their fathers. Calkins repeatedly denied harming the men. He was never criminally charged.

Now 68 years old, Calkins was last known to be living in Iowa. Through his attorney, he declined multiple interview requests from CNN.

Marcia Williams kept a lock of her son’s hair, and a picture of him, wearing a navy blue T-shirt, looking at the camera, which made it seem as if Terrance were looking at her when she walked past. And across the Gulf of Mexico, in the state of Oaxaca, friends and relatives remembered Felipe Santos.

“He didn’t deserve to be disappeared in this way,” his friend Francisca Cortés told CNN. “It isn’t right that he hasn’t been found after so many years and we don’t know what happened to him. As his parents say, ‘If we find his remains, we can give him a Christian burial so we have somewhere to cry and pray for him.’ But in this case there isn’t anywhere. And there isn’t any way to do that. Everything is in limbo and we are never going to know what happened.”

In 2019, a CNN reporter began a new inquiry into the disappearances of Felipe Santos and Terrance Williams. Eventually, two more reporters joined the project. Nearly 70 people were interviewed. The reporters filed dozens of open-records requests with government agencies, yielding more than 10,000 pages of documents and many hours of audio recordings.

Using phone records, dispatch logs and interview transcripts, CNN built minute-by-minute timelines of the days each man disappeared. CNN also obtained every available incident and arrest report from Calkins’s career with the Collier County Sheriff’s Office, more than 2,000 reports from 1987 to 2004. This story is the result of CNN’s efforts to untangle one of the most disturbing unsolved mysteries in the recent history of American law enforcement.

Here is one of the most striking revelations from the Calkins documents: One day in 2001, almost 14 years into his law-enforcement career, Calkins stopped making arrests. That August, he took a man to jail on a misdemeanor charge of domestic battery. The records show that from then on, through almost three more years of road patrol, Calkins never arrested anyone again. He wrote almost 400 incident reports without delivering anyone else to jail.

This glaring deficiency in the deputy’s performance appears to have gone unnoticed at the sheriff’s office. In June 2003, a supervisor wrote that Calkins met the standard in numerous categories, including apprehending and booking suspects. That was almost two years after his last arrest.

“This is the first I’ve heard of it,” Don Hunter, the former sheriff, said in a phone interview when asked about the three-year arrest drought. “I don’t have an explanation for you. I’m surprised, yes.”

Here’s why this could be relevant to the disappearances of Santos and Williams: Both men were unlicensed or uninsured drivers and could have — perhaps should have — been arrested. Calkins did not take either man to jail.

Charles Peterson, a former deputy who went through the police academy with Calkins in 1987, was asked about the three-year gap in Calkins’ arrest history. Peterson said Calkins had lost trust in the justice system.

“He always felt it was just a revolving door,” Peterson said. “They’d be back out on the street before we finished our paperwork.”

Peterson remembered Calkins fondly and shared a picture of him from the police academy. In that picture, Calkins stands out from the other cadets. He is 33, older than many of them, and his muscular arms are so big that they strain at the sleeves of his uniform shirt. Calkins grew up on a farm in Illinois, worked there for more than a decade after high school, took a job as a security guard at a nuclear power plant, and moved to Florida in 1987.

Collier County is in the southwestern corner of the Florida peninsula, between the sawgrass prairies of the Everglades and the white-sand beaches along the Gulf of Mexico. The wealthy and the retired live near the coast and in the upscale city of Naples. Further inland, the median income declines. Calkins’ first patrol assignment was Immokalee, about 40 miles northeast of Naples, where migrant workers labored in the vast tomato fields.

Lucas Benitez, a founder of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, likened police officers in Immokalee to the US Army occupying Iraq.

“It doesn’t know its traditions, its culture,” he said. “They are basically planted there. The Army goes to a small town in Iraq, doesn’t speak the language. The Army automatically feels attacked. What does it do? Aim its rifles. Immokalee was like this.”

Reports from Calkins describe several tense standoffs between deputies and residents. But by many accounts, Calkins handled the pressure well. Supervisors and coworkers got along with him, including some of other races. Walter Solomon, a 6-foot-9 Black deputy who’d grown up in the Bronx, remembered getting together with Calkins at another colleague’s house to practice their shooting and talk about their lives.

“He was quiet,” Solomon said. “He took care of his business, he took care of his job … I never remember him getting in any trouble or anything or getting reprimanded for anything.”

The arrest and incident reports offer a glimpse of what Calkins experienced on patrol in Immokalee. He arrested a 240-pound man whose nickname was Long Knife. He arrested a man who kicked out the window of his patrol car. He arrested a robbery suspect whose right hand had a tattoo that said “Treat me nice” and whose left hand had a tattoo that said “I love Angie.” He reported arresting a man who threw a lit cigarette at him and threatened to urinate in his patrol car and threatened to kill Calkins and his family.

Charles Peterson recalled the time he and Calkins walked up to a mobile home to check out a disturbance when the door swung open and a man came out swinging a machete. Calkins could have used deadly force, according to Peterson, but chose not to. The two deputies managed to disarm and subdue the suspect.

“I was like, ‘Dude, you could’ve killed him. You had the right to shoot and kill him,’” Peterson said. “And he said, ‘I know.’ … I commended him. I was like, ‘Man. You’ve got nerves of steel.’ I was like, ‘Any other deputy would’ve blown him away.’”

In the course of several phone interviews, Peterson seemed to waver in his thoughts and feelings about Calkins. One day, without being asked a question on this topic, he blurted out, “Do I think that Steve Calkins is racist? Yeah. I think he disliked Mexicans and I think he disliked Blacks.”

Minutes later, he backed off this statement, and clarified that what made Calkins really angry “was these Mexicans or Blacks that were uninsured, or driving with no license.” Then he said it wasn’t particularly Black or Mexican drivers who angered Calkins, but “anybody that had no driver’s license or no insurance pissed him off.”

Peterson was asked about the two drivers — one Mexican man, one Black man, both driving without a valid license or insurance — who disappeared after meeting Calkins.

“Do I think they’re alive?” Peterson said. “No. I think they’re dead. And do I think Steve might’ve been involved in it? Good possibility. Is there evidence? No. Why? Because they never arrested him.”

“Could he be a hidden monster inside? Yeah, he could be.”

“I tell you, if Steve was capable and did do it, he would definitely make sure that the body would never be found.”

Felipe Santos was 23 years old when he vanished. He was from a small town in Mexico, and he frequently called home to his parents. He was known for being quiet and polite. Most of his hair was cut short, except for one long strand that he braided. Felipe and his fiancée had a baby daughter. He loved being a father, and he didn’t go out much. A friend said he was most often seen going to and from work or the laundromat. He had worked in the fields and he was saving up his money.

As his brother Salvador wrote in Spanish on an FBI questionnaire after Felipe’s disappearance, “His dreams were to get ahead, to have a home where he lived with his family.”

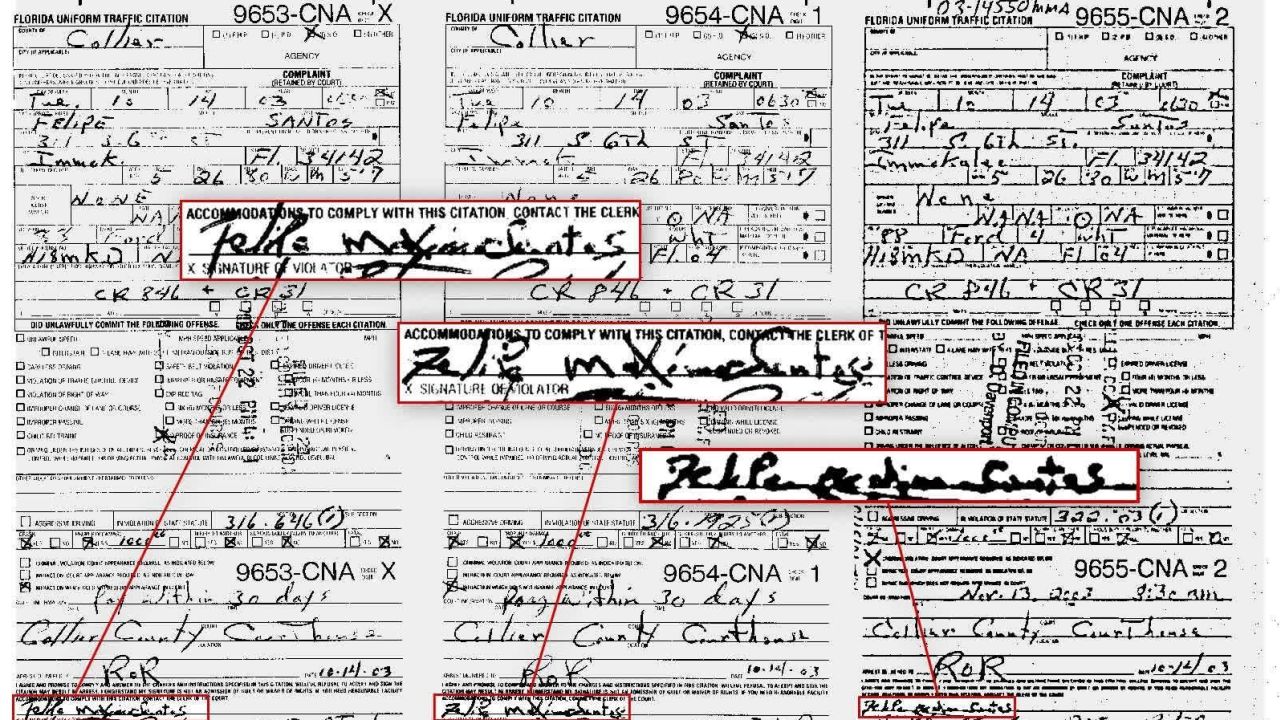

On October 14, 2003, Santos was on his way to work at a concrete and masonry company when his white Ford Tempo collided with a Mazda Protege. Witnesses would later disagree on who caused the crash, or how exactly it happened, but afterwards, Santos and the Mazda’s driver, Camille Lach, pulled into a gas station parking lot. Two of Santos’s brothers were riding with him, and Lach told an investigator that one offered her money if she wouldn’t call the police.

But she did call the police, and Cpl. Steven Calkins arrived at 6:55 a.m. He quickly determined that the crash had been Santos’ fault — and that Santos had no driver’s license or insurance.

Months later, when asked by an investigator if Calkins was “upset,” Lach said, “A little bit, yes … he just said he was tired of this type situation, someone getting in an accident and not having insurance or license.”

The investigator asked Lach if Calkins had raised his voice.

“A little, a little,” she said.

In his account of that morning, Calkins did not say he was angry with Santos. He appreciated how “polite and cooperative” Santos was being. He said he’d given Santos a break.

“I decided to issue him citations for the offenses instead of taking him to the jail,” Calkins told an investigator. “…I didn’t want to leave him by his car, ‘cause I was afraid he was gonna drive off, as I’ve seen in the past. Um, so I went down just a few blocks away to the Circle K store located on Immokalee Road and Winterview Drive. Once there, I brought the driver outside and we talked and I issued him his citations and I gave him a copy of the crash report and I gave him back his car keys and I explained to him not to drive his car anymore until he could get a valid driver’s license.”

There is no evidence that Santos ever arrived at the Circle K, said Kevin O’Neill, a sheriff’s detective who investigated the disappearances of Santos and Williams. Besides that, O’Neill could never understand why Calkins would have driven him there. Santos and his brothers weren’t far from work, and their foreman was on the way to pick them up. But he never got to work that day. His foreman kept calling the jail. Santos wasn’t there.

“That’s when the ordeal, the confusion began,” recalled Lucas Benitez, the Immokalee farmworkers’ advocate who was also a friend of Santos’ family. “He had been taken, but he wasn’t in the jail. They couldn’t pay the bond because he wasn’t there.”

Relatives wondered if he’d gotten sick, so they started calling hospitals. Santos was undocumented, so they also wondered if he’d been picked up by immigration authorities. But their inquiries all led back to the same place: the deputy sheriff who put Santos in the back of his patrol car and drove him to some unknown destination.

Another mystery from that morning involves the signatures on the three traffic citations that Calkins gave Santos. On two of the tickets, in the space for SIGNATURE OF VIOLATOR, the middle name appears to be “Maximo.” On the third, the signed middle name appears to be “Medino.” Neither of those is Santos’s actual middle name: Maximino. And the signature looks nothing like a previous signature found on Santos’ school ID card.

Investigators submitted the signatures from the tickets to a handwriting expert to see if they matched the handwriting of Calkins. The expert said no, according to a sheriff’s investigator. Those signatures “were written by someone other than Cpl. Calkins.”

But if Santos didn’t sign the tickets, and Calkins didn’t forge the signatures, who signed the tickets? A CNN reporter posed this question to Doug Molloy, the former chief assistant US attorney who supervised the investigation into the disappearances. Molloy said his team looked into the possibility that if Calkins harmed the men, someone helped him do it. But investigators could find no evidence for that.

It’s hard to know for sure what Calkins did after leaving the crash scene. Patrol officers were not monitored as closely then as they are now, and there is no record of his minute-by-minute whereabouts — other than what Calkins himself reported to dispatch.

“When you have a target,” Molloy said, “you don’t assume anything that he says is true.”

At 7:35 a.m., Calkins reported clearing the call, meaning he was no longer handling the Santos crash. He wrote that he went to a morning briefing at the sheriff’s substation after that, but it’s not clear from the records whether anyone saw him there that day.

From 7:59 to 8:19, according to dispatch records, Calkins reported that he was doing an extra patrol at SITE 123, or Naples Park Elementary School. Kathy Maurchie, a dispatcher who worked with Calkins, reviewed the dispatch logs at CNN’s request. She was skeptical of this claim.

“You can be gone as long as you want, and nobody’s gonna question it, and nobody’s gonna try to dispatch you either,” Maurchie said of the extra patrol. “So yes, it’s a convenient way to go off the grid.”

At 8:53 a.m., Calkins reported arriving at North Collier Hospital, where he took a report about an underage girl giving birth. Investigators found it likely that he was, in fact, at the hospital.

If Calkins really did leave the crash scene at 7:35, that means he had an hour and 18 minutes before he got to the hospital. But Camille Lach reported seeing Calkins leave much earlier, just after 7 a.m., and a brother of Santos gave a similar estimate. Lach told investigators that Calkins had already departed with Santos by the time she left around 7:05.

If Calkins left with Santos at 7:05 and was not seen again in the course of his law-enforcement duties until arriving at the hospital at 8:53, that leaves an hour and 48 minutes during which his whereabouts and activities couldn’t be determined with certainty. Molloy, the former federal prosecutor, said “that period of time is probably the most vital period of time to examine and explore.”

He went on: “I’m comfortable saying that we went over his patrol area, we went over areas that one could reach in that period of time … We dragged lakes … We examined every possible place that … he could have reached and gotten to the hospital.”

It’s not clear whether investigators analyzed any location data from Calkins’s agency-issued Nextel phone. No such records were included in the reports released by the sheriff’s office to CNN, and in 2021 agency spokesperson Karie Partington wrote, “There is no location data available for the phone.”

There are other gaps in the public record, too. The available dispatch records for Calkins on the day Santos disappeared only cover the time from 6:45 to 11:19 a.m., less than five hours and nowhere near a full shift. When asked why, or whether Calkins worked only a partial shift that day, Partington did not have an answer. “We have provided all records we have regarding this,” she wrote. Thus, what Calkins did after 11:19 a.m. that day is unknown.

On October 29, about two weeks after Santos disappeared, his brother Jorge filed a citizen’s complaint against Calkins.

“Brother lost after (Badge) 235 put him Felipe inside of Patrol Car…” he wrote. “Felipe never got home.”

The sheriff’s office opened an internal-affairs investigation and assigned it to Sgt. Doug Turner, who had previously worked as a patrol deputy alongside Calkins in North Naples. As an internal-affairs investigator, Turner was used to interviewing people he called “frequent flyers” — that is, deputies who generated a lot of citizen complaints — but Calkins was not one of them. On November 4, three weeks after Santos disappeared, Turner interviewed Calkins about it. And he found the story a little strange.

“I could not get Steve to engage me,” he told CNN. “And just whenever I asked him a question, he would go directly to the report and just start reading from the report or the memo that what he wrote … He was pretty much like reading from a book. Instead of just, you know, talking to me. Tell me in your own words, what happened.”

Turner recalled wondering, “Why didn’t you take him to jail? Why did you take him to the Circle K? You know, he said he’s trying to give him a break and stuff like that, but it was just — it was just odd, you know? But you also look at it as, here we’ve got a veteran officer that’s been on the job for, you know, 15 years at the time or so. He was just getting burned out, lazy or whatever, and just didn’t want to do paperwork.”

As for what happened to Santos, Turner recalled thinking, “Maybe he just left.”

On November 27, a judge issued a bench warrant for Santos after he failed to appear in court. That same day, Capt. Jim Williams reviewed the internal affairs investigation of Calkins and wrote, “I can find no basis for linking Cpl. Calkins with the alleged disappearance of Santos … I believe that Calkins’s actions in this situation were reasonable, lawful and proper.”

On December 2, Calkins was exonerated of “carelessness in duty performance” in the disappearance of Felipe Santos. Forty-one days later, Calkins was back on patrol when he saw Terrance Williams driving an old white Cadillac.

There is no way to know what time Calkins first saw Williams on January 12, 2004, because Calkins did not report the traffic stop to dispatch as it was happening. A full week later, when Calkins finally wrote his report, he said he saw the white Cadillac around 12:15 p.m.

But this is probably not true. It may not even be close. Terrance Williams was 27 years old, and he had learned a few things as a Black man in America. Friends said Williams had encountered the police enough times to have a policy: When an officer pulls you over, do your best to make sure there are witnesses.

And there were witnesses — at least three. They all told investigators the traffic stop happened before 10 a.m., and perhaps as early 9, about three hours earlier than Calkins would later claim. Further contradicting the timeline put forth by Calkins, Williams was scheduled to start his shift at Pizza Hut at 10 a.m. that day.

With Calkins on his tail and the cruiser lights flashing, Williams pulled into a parking space at the Naples Memorial Gardens cemetery, in view of an administrative building. Jeff Cross, who worked there as a family service counselor, was standing on the porch when the two cars pulled in. He told CNN that both men got out of their vehicles, and the deputy patted Williams down, and Williams kept patting his pockets and putting his hands in the air, making it clear he didn’t have a driver’s license. Calkins put Williams in the back of his patrol car and drove off.

What happened next is unknown, because investigators found Calkins’ own account unreliable. He took one polygraph test with inconclusive results, one that showed no indication of deception, and a third test that did indicate deception. Regardless, some of his statements contradicted the verifiable facts. Here are three more claims from Calkins that others dispute or find implausible:

1. “The vehicle appeared to be having problems … The driver said he just bought the car and it was not running right.”

In his report, Calkins said this is why he pulled Williams over — the Cadillac wasn’t running properly. But later, in a legal deposition, Williams’ mother, Marcia, said, “Nothing was wrong with that car.” Williams’ stepfather told CNN the same thing: After they recovered the Cadillac from the tow yard, Marcia started it up and drove it home.

2. Calkins claimed Williams told him “that he was now late for work … And he asked me if I could please give him a ride.”

In her deposition, Marcia Williams said her son would never have asked a police officer for a ride, because “he can’t stand them.”

3. According to Calkins, Williams “asked me again for a ride so that he would not lose his job and that it was just up to the Circle K at Wiggins Pass Road.”

The Calkins report suggests that he drove Williams to the Circle K because Williams worked there or somewhere nearby. But neither is true. Williams worked at a Pizza Hut more than two miles away from that Circle K. Even if Williams had asked Calkins for a ride, there is no discernible reason he would have asked for a ride to the Circle K. In any case, investigators never found any confirmation that Williams was seen at the Circle K that day.

Jeff Cross, one of the cemetery workers, watched Calkins drive away with Williams in the patrol car. He expected Williams to be arrested for driving without a license or valid registration. And so he was quite surprised when a detective showed up eight days later to ask him about Williams’ disappearance.

“It still bugs me to this day, because I feel like he got away with something,” Cross said, referring to Calkins. “We all thought that he had taken him somewhere to never be seen again.”

Sometime after noon that day, Calkins returned to the cemetery to have the Cadillac towed away. At 12:49, he placed a recorded call to dispatch. It was answered by Cpl. Dave Jolicoeur, a patrol deputy who had worked in North Naples with Calkins. Jolicoeur was filling in on the dispatch desk, as deputies sometimes did for extra pay.

“Yes, this is One Alpha 30 North Naples,” Calkins said, “could you run a VIN for me, please?”

“For 30 bucks,” Jolicoeur replied. “You gotta give me 30 bucks first.”

“How about 20,” Calkins said, going along with the joke. Both men laughed heartily and said things that were hard to decipher on the recording. Then Calkins changed his accent and began using what an internal review later called “unprofessional faux African American jargon.”

“I got a homie Cadillac on the side of the road here,” Calkins said, “signal 11, signal 52, nobody around.”

Signal 11 meant it was abandoned, and Signal 52 meant it was disabled. Neither description was true.

“The tag comes back to nothin’, it’s a big old white piece of junk Cadillac,” Calkins said. “I’m towin’ it.”

After relaying the vehicle identification number to Jolicoeur, Calkins said, still using his fake accent, “It’s gonna come back to one of the brothers up in Fort Myers.” Both men laughed again. Jolicoeur looked up the number in a database and told Calkins the vehicle had no assigned registration. They laughed some more.

“It’s a homes’ car,” Jolicoeur said.

“We just drive it, man,” Calkins said.

“We don’t follow no rules, sucka,” Jolicoeur said.

“We just be drivin’ it,” Calkins said.

When Jolicoeur asked where the car was, Calkins said it was at the cemetery at the corner of Vanderbilt and 111th.

“Maybe he’s out there in the cemetery,” Calkins said, referring to the Cadillac’s driver. “He’ll come back and his car will be gone.”

After Williams was reported missing and investigators heard the tape of this call, the Collier County Sheriff’s Office reprimanded both deputies for conduct unbecoming a law enforcement officer. In an interview with CNN, Hunter, the former sheriff, was asked about the phone call. “It further induced suspicion,” Hunter said.

Later, Calkins admitted in a letter to the sheriff that his words were “in poor taste.” After Calkins submitted to a psychological assessment in 2004 to see if he was still fit to serve as a deputy, an investigator’s report said that “Calkins does not appear to have a strong racial bias.”

When Jolicoeur was interviewed about what he said on the call, he said it was “inappropriate slang,” and “regrettably, I used poor judgment.”

Jolicoeur declined an interview request from CNN. He told an investigator that some of his banter with Calkins was derived from a scene in the 1983 film “Sudden Impact,” starring Clint Eastwood as the police detective “Dirty” Harry Callahan. In that scene, Callahan shoots four Black men while foiling an armed robbery in a coffee shop.

Jolicoeur recalled a conversation with Calkins “where we were talking about the Dirty Harry movies and how we, we really liked them. And then I started talking about the, that particular scene where the guy says ‘sucker’ and all that and it just kind of became something that we said a lot between the two of us. And, and actually if you talk to the guys on my shift, I say that all, we say that a lot, because I just, I just found that scene to be very funny when it hit me.”

“Sudden Impact” is a classic vigilante film. In this genre, the justice system is typically seen as a failure, and the protagonists take the law into their own hands.

In his report, Calkins described a conversation that he claimed to have had with Williams as he dropped him off at the Circle K:

“I told him he had better make plans right away to get his car and he said that he would take care of it, and he thanked me. I asked him for his name and he said Terrance. I also warned him that his tag was expired but he said the receipt and proper registration were in the glovebox, if I wanted to check it out.”

Calkins wrote that he went back to the Cadillac, checked the glovebox, and found it empty.

“I now phoned the Circle K and asked for Terrance and the clerk that answered the phone said she did not know any Terrance,” he wrote, although investigators checked his phone records and could find no proof that he called the Circle K. “I now felt that that Terrance had deceived me. I now called for a wrecker … thinking that the Cadillac was now abandoned … and maybe even stolen. After Coastland Towing removed the car, I went back to the Circle K and the surrounding area to search for Terrance … but I could not locate him.”

Investigators would consider another possibility: Calkins did find Williams again.

Shortly after 1 p.m., Calkins called dispatch with some new information. In previous calls about the Cadillac at the cemetery, he had not mentioned Terrance Williams’ name. But at 1:12 p.m., he called to ask for a warrants check on Terrance D. Williams. He said the date of birth was April 1, 1975.

Investigators found this significant because it was not Williams’ real date of birth. It was a false one that Williams sometimes gave the police when he was in a jam. That date of birth was not written on any official documents that Calkins could have found. Sgt. Mike Koval of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office wrote that he told Calkins, “it appeared that he had made contact with Terrance Williams a second time.”

Calkins denied this. According to Koval’s report, Calkins said, “the entire incident with Williams had been so routine, so trivial; he just did not remember the kind of things we keep asking.” Thus, Calkins had trouble explaining how he got the new information about Williams.

“You only know that this guy is Terrance, there is no paperwork in the car, it doesn’t come back registered, but now when you call, you’ve got his full name, Terrance D. Williams, and you’ve got his date of birth,” Koval said. “Where did you get it? Because the date of birth you gave, absolutely nobody knows but Terrance.”

“Humph,” Calkins said.

“It’s on absolutely no documentation anywhere,” Koval said. “So 13 minutes after the car’s towed and you go back looking for Terrance, you now have all his information. My question is, where did you get it?”

“Where did I get that date of birth?” Calkins said.

As Koval kept pressing him, Calkins sighed.

“Oh brother,” he said, “I’m all confused again.”

Dispatch records show a gap of 53 minutes, from 1:01 to 1:54 p.m., in which Calkins did not respond to any calls. He called for the warrants check on Williams during that time. Later, when Calkins failed a polygraph test from internal affairs, the question that elicited the strongest reaction indicating deception was, “Was Terrance with you when you ran his 4/1/75 DOB over your Nextel?” The second-strongest reaction came after the question, “After you dropped Terrance at the Circle K, did you have any further contact with him?”

The gap of unaccounted time that afternoon may be much longer than 53 minutes. At 1:54, Calkins reported to dispatchers that he was conducting a traffic stop, and at 2:18 he reported having written a citation. Dispatch records indicate that Calkins called in license plate numbers both times he claimed to be making a stop that day. But investigators never found the citation he supposedly wrote that afternoon. Nor did they find another one he supposedly wrote that morning.

A CNN search of court records showed that Calkins issued ticket number 9661-CNA five days before Williams disappeared, and he issued ticket number 9663-CNA the day after Williams disappeared. According to an investigator’s report, “Citation number 9662-CNA is unaccounted for and was never turned in by Calkins.”

Sheriff’s spokesperson Karie Partington said, “Detectives did check to see if he had issued a verbal or written warning but no documentation could be located.”

In other words, there is no definitive proof that either traffic stop was real.

Calkins did not write many tickets — an average of about one per month the previous year — but he claimed to have written two the day Williams disappeared. Both of these questionable traffic stops occurred during time windows in which he could have encountered Williams: the first at 9:50 a.m., around the time the cemetery workers said they first saw Calkins and Williams; and the second at 1:54, not long after he called dispatch with the secret false date of birth.

“I have an idea why he’d do that,” said Molloy, the former federal prosecutor. “Because he was up to no good.”

“When you’re doing something that you shouldn’t, you make sure that somebody sees you in a way that would help cover it.”

If Calkins faked the second traffic stop, and if he actually responded to the residential-alarm call that appears in dispatch records at 2:51, it means he had an unbroken span of an hour and 50 minutes that afternoon during which his whereabouts and activities were unknown.

After Williams disappeared, his mother called jails, hospitals, morgues and mental institutions. No one at any of those places had seen him. She also called junkyards, and eventually found the one that had the Cadillac. At the junkyard she was told it had been towed from the cemetery, and at the cemetery the employees said they’d seen a deputy sheriff taking Terrance away.

So Marcia Williams called the sheriff’s office and spoke with Kathy Maurchie, who looked up the towing records. They showed that Cpl. Steven Calkins had a Cadillac towed from the cemetery on the day in question. On January 16, 2004, four days after Williams was seen with Calkins, Maurchie called Calkins on a recorded line:

KATHY MAURCHIE: I hate to bother you at home on your day off, but this woman’s been bothering us all day. [LAUGHS] You towed a car from Vanderbilt and 111th on Monday? A Cadillac? Do you remember it?

STEVEN CALKINS: No.

KATHY MAURCHIE: [PAUSE] Do you remember — she said it was near the cemetery.

STEVEN CALKINS: [PAUSE] Cemetery.

KATHY MAURCHIE: Anyway, the people at the cemetery are tellin’ her you put somebody in the back of your vehicle and arrested him, and I don’t show you arresting anybody.

STEVEN CALKINS: I never arrested nobody.

KATHY MAURCHIE: That’s what I thought. Okay.

STEVEN CALKINS: I gotta think about this one for a while.

KATHY MAURCHIE: But you’re sure no one was with that vehicle.

STEVEN CALKINS: No.

KATHY MAURCHIE: It was around 12:30 in the afternoon?

STEVEN CALKINS: [SILENCE] [LAUGHS] Jesus, I can’t remember.

KATHY MAURCHIE: [UNINTELLIGIBLE] … you’re gettin’ to be my age, huh? [LAUGHS]

STEVEN CALKINS: Damn.

KATHY MAURCHIE: [LAUGHS]

STEVEN CALKINS: What do they want?

KATHY MAURCHIE: Well, there’s somebody at the cemetery who’s telling the mother that you picked up the driver and he’s been missing since Monday.

STEVEN CALKINS: Oh, for Pete’s sakes.

KATHY MAURCHIE: And I said, “He didn’t arrest anybody.”

STEVEN CALKINS: No.

KATHY MAURCHIE: But she keeps calling and (saying), ‘Well, there’s got to be some way you can get a hold of ‘im.’ … I think she spoke to every dispatcher in here today.

STEVEN CALKINS: [SIGHS]

KATHY MAURCHIE: Anyway, I was trying to figure out what color the Cadillac was. I forgot. I got it right in front of me. You picked it up at 12:27, on Vanderbilt and 111th. And Coastland came and got it. A large white Cadillac.

STEVEN CALKINS: Large white Cadillac. I got to look it up in my notes. I don’t remember. God almighty.

KATHY MAURCHIE: But you’re sure you didn’t — you’re sure there was no one with it?

STEVEN CALKINS: No.

Later, an investigator would review this tape and write that Calkins’ statements to Maurchie were “inconsistent with the known facts.”

In an interview with CNN, Maurchie would go a step further.

“I think he’s guilty,” she said. “Guilty as sin.”

One by one, deputies who knew Calkins were interviewed by state investigators. And one by one, those deputies said they believed Calkins had done nothing wrong. Their statements were striking in their similarity. They said Calkins had not privately admitted to misleading investigators. And most of them mentioned rumors that Terrance Williams had been seen alive, in East Naples, days after his encounter with Calkins.

Their statements mirrored one from Calkins himself, who also told an investigator that Williams was probably alive in East Naples.

“I think he’s down there, sneaking around in drag or something,” Calkins said.

One source for these rumors was a gas-station clerk who claimed to have seen Williams a week after his ride with Calkins. The clerk told a deputy sheriff that Williams regularly came into the Sunoco to buy prepaid phone cards, and said Williams came in again on January 19. According to a deputy’s report, the clerk said he and Williams “spoke for a while and Terrance said that he had to lay low the heat was on. Terrance left the Sunoco in a brown early 70’s Cadillac.”

An investigator followed up and reviewed the surveillance video with the clerk. The investigator saw the clerk on the tape but did not see Terrance Williams.

CNN asked Kevin O’Neill, the longtime case detective, and Doug Molloy, the former federal prosecutor, about this and other supposed Terrance Williams sightings. Both said there was no evidence Williams had been seen after he met Calkins.

Nevertheless, about six months after Williams disappeared, Sheriff Don Hunter circulated a “position statement” about the “apparent disappearances” of Santos and Williams. It alluded to legal trouble both men had. Santos was an undocumented immigrant who would have to answer for driving without a license. Williams faced no local charges, because Calkins hadn’t arrested or ticketed him, but a judge in Tennessee had issued a warrant for Williams in connection with unpaid child support.

“These men may therefore be purposely avoiding being found by law enforcement,” the sheriff’s statement said.

Julia Perkins, who knew Santos through the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, did not like what the sheriff was implying.

“That just seemed like an excuse,” she said. “And honestly, it was a slap in the face to the families.” Like others who knew Santos, she found it implausible that he would have willingly left behind his common-law wife and their three-month-old daughter. A picture showed him cradling the baby in his arms.

“He was not a person who was going to abandon her,” Lucas Benitez said. “He loved Apolonia and he was very happy about his girl’s arrival. They didn’t have any problems between them. They were two young people starting a life. They had dreams and plans together.”

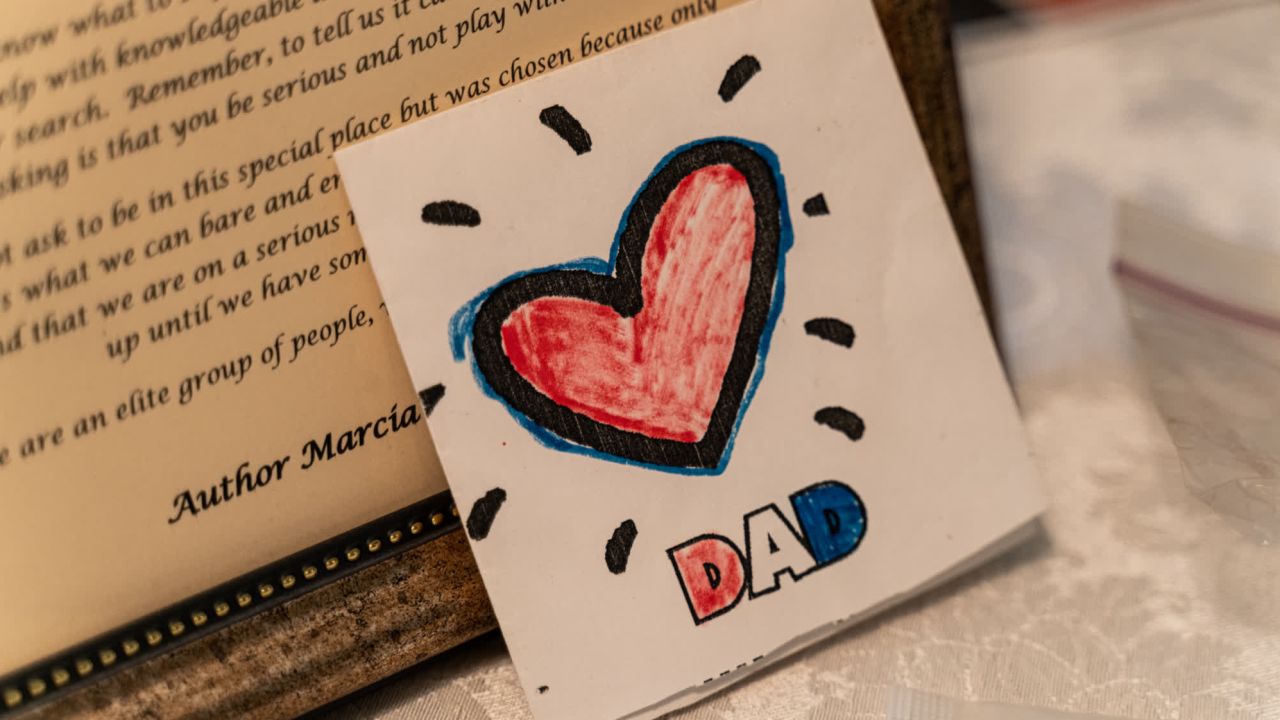

Likewise, Terrance Williams had reasons not to disappear. Terrance’s young son Tarik lived nearby with Terrance’s mother, Marcia. Terrance and Tarik played video games and went to the mall together, and Terrance regularly cut Tarik’s hair. He was a skilled barber who dreamed of opening his own shop. His mother was sure Terrance would have called her if he could. She said he used to call her two or three times a day.

Marcia Williams did not trust Sheriff Don Hunter. She was not the only one who believed that someone in the sheriff’s office was hiding the truth. A former sheriff’s office employee who spoke with CNN on condition of anonymity said people of color had a lot of trouble with the deputies of North Naples in the early 2000s, and that Black youths had been unfairly followed and harassed. The former employee — who worked there while Calkins did — said Calkins was merely “the scapegoat” in Williams’s disappearance.

“I do not think one deputy did all this by himself,” the former employee said.

When a CNN reporter mentioned how hard it was to persuade other deputies to talk about Calkins, the former employee said, “Blue don’t tell on blue.”

Hunter, the former sheriff, said he and his investigators did all they could to find the truth. He said the position statement was reasonable given the uncertainty about what happened to Santos and Williams. He recalled meeting with Marcia Williams, and said, “She seemed to understand that we were making an extraordinary effort to try to locate her son.”

Hunter said he didn’t remember any complaints about deputies harassing Black youths in North Naples, and he wouldn’t have tolerated such conduct from his employees. He said no other deputies were suspected of involvement in the disappearances of Santos and Williams. And he described meetings around a conference table with state and federal law-enforcement officials in which they all racked their brains for a strategy that might answer their questions about Calkins.

“Let’s go right now and raid the house,” Hunter said he heard someone say at one of the closed-door meetings. “Raid his house.”

But they never did, because they didn’t have a warrant. The investigators were “on the edge of violating rights,” Hunter said, but they held back.

“The Constitution does not permit us to dispense with rights,” he said, “even on a law enforcement officer, even if you might hold a suspicion, which of course I did.”

Hunter served as sheriff until 2009. These days he spends much of his time in North Carolina, but he can’t leave the Calkins mystery behind.

“It’s not haunting me,” he said, “but it’s never too far from my mind.”

Sometime after he was fired from the sheriff’s office, Calkins took a job at a local UPS facility. He worked there until 2013.

“Just wanted to let you know that (Calkins) quit his job at UPS yesterday,” a sheriff’s investigator wrote to Chief Jim Williams on March 29, 2013, in an internal email obtained by CNN through an open-records request. “Apparently he caused a minor scene and was escorted out.”

According to an investigator’s report, a UPS supervisor noticed that packages were getting jammed on one of the conveyor belts where Calkins was working. When the supervisor talked to Calkins about it, Calkins refused to do what he was told. Instead he started yelling curses, including “f**k you,” at various coworkers. When he was escorted to an office, he tendered his resignation by writing, “I Quit.”

After getting the report on Calkins’ departure from UPS, Chief Williams emailed one of the investigators to ask what kind of vehicle Calkins was currently driving.

“Without employment he potentially represents a threat to anyone he blames for his circumstances,” Williams wrote.

Investigators kept tabs on Calkins and learned in 2016 that he and his wife had sold their house and moved to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. With permission from the new owners of the former Calkins home, investigators conducted a search of the Florida property.

They brought in cadaver dogs. They used ground-penetrating radar. They consulted with Heather Walsh-Haney, a forensic anthropologist who analyzes skeletal remains. They identified an area near a concrete slab in the backyard where the soil appeared to have settled in an unusual way. A contractor removed the concrete and noticed that it was of a lesser grade than the concrete elsewhere on the property. Investigators found “several pieces of black plastic and a piece of electrical cord,” a report said.

The plastic and the cord were sent to an FBI lab for testing. But the FBI said the items couldn’t be tested because they’d been underground too long and their texture wasn’t conducive to retaining DNA.

The search of the yard was one more dead end.

“There were no human remains discovered,” the report said.

In 2018, with representation from the civil-rights lawyer Benjamin Crump, Marcia Williams filed a wrongful-death lawsuit against Calkins. The complaint said “the facts circumstantially establish” that Calkins “intentionally murdered or otherwise caused the death of Terrance D. Williams.” In 2020, Calkins’ attorney, John Hooley, took Marcia Williams’ deposition.

He asked her about Terrance’s Cadillac: when he bought it, what condition it was in, when he took it to a mechanic, and so forth. She wasn’t quite sure of the dates.

“If I had everything here, then I could show you,” Marcia said, trying to gather her thoughts, “but I don’t have everything here.”

“What don’t you have that you need in order to answer your questions?” Hooley asked.

“My son,” she said.

Hooley asked about the incident report that Calkins wrote regarding his encounter with Terrance Williams.

“Did you — when you read the report,” the attorney asked Marcia Williams, “was there anything in the report that indicated that Steve Calkins had killed Terrance Williams?”

“I’m pretty sure he wouldn’t put that in the incident report,” she said.

Later in the deposition, during a back-and-forth about Calkins and the tow truck, Marcia said,

“Steve Calkins had evil intent that day.”

“This man did something to my child and he’s the only one that can answer.”

“How do you know?” Hooley asked.

“I know, because a mother — a mother knows and you can’t take that out of a mother’s gut.”

“But you don’t have any evidence that he did anything?”

“I don’t have to,” she said, “but God does.”

Later in 2020, the case entered non-binding arbitration. The court-appointed arbitrator, Robert E. Doyle Jr., wrote, “The evidence presented does not show Defendant Calkins in a good light. He has told more than one story about what happened with some contradictions. His version of the interaction with Terrance Williams is not believable … Further, the information he related about the disappearance of Felipe Santos is eerily similar to what he said about Terrance.”

But unlike the investigators, Doyle determined it was possible that Williams had been seen alive after the day he encountered Calkins — even though the State of Florida declared Williams legally dead in 2009. The arbitrator wrote, “Being an uncredible witness or even a liar does not make Calkins a murderer or guilty of manslaughter.” He entered a nonbinding judgment in favor of Calkins.

At that point, the wrongful-death suit could still have gone to a jury. But after the Crump legal team missed a filing deadline to ask for a trial, a judge dismissed the case. The Crump team said the Covid-19 pandemic had caused interoffice confusion that led to the missed deadline, but a Florida appeals court upheld the dismissal. And a judge ruled that Marcia Williams and her son’s estate had to pay Calkins about $5,600 for costs related to the lawsuit.

Sometimes, when former deputies get together in Naples, they talk about Steven Calkins.

“And it’s like, ‘Do you think Steve did it?’ You know, that’s the big lingering question,” said Doug Turner, who patrolled North Naples with Calkins in the ’90s. “And, you know, whenever I’m asked, I’m like, ‘I don’t know. And I’m always like, ‘Well, you know, if he did, where’s the bodies?”

Dennis Damschroder, another deputy who worked with Calkins, told CNN he thought Calkins was innocent. One reason he believed that, he said, was the logistical challenge of secretly killing someone during a patrol shift.

“If you wanted to kill me at 12 o’clock in the afternoon, what are you going to do with my body?” Damschroder said. “If he did something with them, why haven’t they found them?”

While questioning Calkins in 2004, Cpl. Scott Walters complained about the inconsistencies in Calkins’ statements. CNN obtained a recording of the conversation. Walters said, “Every time we ask you a question, we have to go back and get clarification. And every time we have to go back and get clarification, it makes it look like you’re trying to hide something. And if you’re trying to hide this, what else are you trying to hide? Do we got a body laying around in the sticks somewhere that we don’t know about?”

Calkins said nothing, but he laughed.

“I mean,” Walters said, “are we gonna be clearing, are we gonna be widening Immokalee Road down through Wiggins Pass some day and all of a sudden find out that we got a dead body out there like they keep digging all these dead bodies up out there?”

Calkins said nothing, but laughed again.

In the woods along Immokalee Road, which ran from his patrol zone in North Naples all the way to Immokalee, three sets of human remains had been discovered in the previous ten months. Two were unidentified, and remain so today. One was Sergio Guerrero, a man with no known connection to Calkins.

Guerrero was an undocumented Mexican immigrant who began appearing in sheriff’s reports from North Naples in 1995. He worked as a dishwasher and a tile setter, among other jobs. In many of the reports, Guerrero is described as “drunk” or “intoxicated.” Often he was on foot, staggering in the road, but sometimes he drove a truck or rode a bike.

Among the documents provided to CNN by the Collier County Sheriff’s Office, none show a direct encounter between Calkins and Guerrero. In 1998, Calkins was listed as the “editing supervisor” on another deputy’s report that described Guerrero drunkenly crashing a bicycle into a motor vehicle.

In January 2003, deputies arrested Guerrero on a probation-violation warrant. While he was in jail, federal immigration authorities took custody of him. On March 20, Guerrero was deported. But he quickly returned to the United States, and to North Naples.

A friend said Guerrero’s wife had reported seeing him on a Sunday, “at Easter time,” according to a sheriff’s report. Easter fell on April 20 that year. There were no reported sightings of Guerrero after that.

On June 3, 2003, a worker from an excavation company found human bones in the woods south of Immokalee Road. The remains included a skull in two pieces, scattered vertebrae, and a broken pelvic bone. An investigator wrote that “no flesh was visible” on the bones. The skull showed evidence of a gunshot wound, possibly from a .32-caliber bullet. Subsequent DNA testing identified the remains. This was Sergio Guerrero.

A sheriff’s report said Guerrero’s former employer and friend had wired him some money to help return to the United States. The employer later tried to collect the debt and admitted to a detective that he threatened to report Guerrero to immigration authorities if he didn’t pay it back. Guerrero told his family he was worried for his safety. CNN reached the employer, Nick LaGrasta, and asked what he thought had become of Guerrero.

“I think he was at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and got picked up by the wrong person,” LaGrasta said.

Guerrero’s bones were found about a mile away from the Circle K where Calkins claimed to have dropped off Felipe Santos.

Molloy, the former federal prosecutor, was asked if the FBI looked for connections between the cases.

“It is my understanding that they did,” he said. “We were not able to find any connection between Calkins and other bodies we may have investigated.”

Steven Henry Calkins was born in 1954 in Ottawa, Illinois. His father was a timber broker and a deacon in the Baptist church. His family raised corn and soybeans. Calkins lived in Illinois for 33 years and did not leave much of a footprint. He rarely appeared in his 1972 high school yearbook. The local law-enforcement authorities said they had nothing about him in their files. He worked on the family farm for 14 years after high school. In 1983, he served as a groomsman in a friend’s wedding. That friend, Jeff Gleim, remembered Calkins as a good man.

“Well, the last I knew about Mr. Calkins was he was an upstanding farmer up by Grand Ridge. And he did an excellent job farming. And he was a friend for a long time, and then he was a police officer somewhere down South,” Gleim said. “If he is the same caliber of a police officer as he was a farmer, the state of Florida has the best officer that they ever could hope to have.”

Many people did see Calkins as a good officer. He saved at least two lives as a deputy sheriff. In 1996, he and a colleague found a man unconscious in a chair in his living room after an apparent heart attack. They administered CPR until other rescue workers arrived, and the man survived. That same year, after a vehicle crash, Calkins found another man pinned beneath a pickup truck. Marshaling bystanders to help, Calkins led an effort to lift the truck and set the man free.

There were smaller things he did, too, acts of kindness that led citizens to write letters of thanks to the sheriff. They said he was courteous and professional. They said he went above and beyond. Calkins “made a very tense situation calm,” one woman wrote, and another said he “did more than he had to,” and once, on a cold, windy night just after Christmas, he saw an elderly couple with car trouble and he drove them home.

One day in 1991, a woman was driving on Interstate 75 with her four-year-old son when her Dodge Caravan broke down. Calkins wasn’t even on duty; he was driving home after having his cruiser serviced on his day off. But he helped get the broken-down minivan off the highway and then put the woman and the boy in the cruiser. They were on their way to pick up the woman’s 6-year-old son from school, so Calkins drove them to pick up the boy. Then he drove all three of them home.

“To say the least, my sons had a great time riding in the back seat cage of the marked, police vehicle and were the envy of all their friends at the community school,” the boys’ father, Patrick O’Mara, wrote to the sheriff.

To Calkins’ attorney, John Hooley, these incidents are evidence that Calkins is innocent.

“If you look at his personnel file, you’ll see the type of guy he is,” Hooley said. “This guy is more Andy Griffith than he is a guy who would take Terrance Williams on a one-way trip to the Everglades.”

This leads to the conflicting questions at the heart of the story. If Calkins really is a guy who would make people disappear, how did he keep his badge for 16 years? Why wasn’t he linked to other disappearances before that? Why did he have so few citizen complaints, and so many letters of commendation?

And if he really is Andy Griffith, why did two men disappear after riding in his patrol car? And why did he lie so much about it?

CNN made numerous efforts to reach Calkins and ask him about his life, his career, and the two disappearances. Hooley, his attorney, said Calkins declined to be interviewed. CNN sent a list of questions to Hooley and asked him to share them with Calkins, but Hooley said he wouldn’t do it.

“He said don’t forward any of your emails to him anymore,” Hooley told a reporter.

Finally, CNN sent the list of questions to Calkins’ last known address in Iowa, requesting a signature confirming delivery. But on April 5, a FedEx employee called to say that after repeated attempts to deliver the package, “we made contact with the recipient, and he refused it.”

To investigators, Calkins is a cipher. An unsolved puzzle. Detective Kevin O’Neill investigated the disappearances for 13 years. He was asked if he understood Calkins at all.

“No,” he said. “No I don’t.”

Doug Molloy, the former federal prosecutor, was asked who Calkins is.

“Nobody I’ve ever encountered before,” Molloy said.

In interviews with sheriff’s investigators, Calkins said nice things about the men who disappeared. Santos was “very courteous and polite and very cooperative,” and “very, very nice.” Williams was a “clean-cut looking young man. Very soft spoken and very, very mannerly and very respectful of me and very well-spoken.”

CNN obtained recordings of some of the Calkins interviews. They include a moment in which he apparently did not know he was being recorded. And in that moment, his description of the two men was entirely different.

In his deep, authoritative voice, Calkins was complaining about the investigation. He said he’d already given too much information. He said he wouldn’t talk anymore without representation. He said he might have broken some rules, but he hadn’t broken any laws. Finally, he said,

“I’m not gonna get drug through the mud no more because a couple of scumbags are missing.”

But these two men had names, and souls, and heartbeats, and fingerprints. They loved, and they were loved, and they were gone too soon.