CNN

—

It’s a day seared into America’s collective memory: December 7, 1941.

The day Imperial Japanese warplanes launched a devastating surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, sinking or damaging 19 US Navy ships, destroying 180 US aircraft and killing more than 2,400 Americans, servicemen and civilians.

“A day that will live in infamy,” in the words of US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. And as the history books have it, the day that dragged the United States into World War II.

But the first Japanese sinking of an American warship was not on that day, or even that year – and it was nowhere near Pearl Harbor, or even US soil. It was four years earlier, on a much less remembered date, thousands of miles from Hawaii, on a river deep in China.

On December 12, 1937, the US Navy river gunboat USS Panay and three Standard Oil Company tankers were evacuating American citizens trapped by Japan’s invasion of Nanjing when they were targeted from above in an attack that, like Pearl Harbor, stood out both for its mercilessness and the fact that the US and Japan were not at that time at war.

Nine Nakajima fighters strafed the convoy with machine gun fire, shooting even on its lifeboats, while three Japanese Yokosuka rained down at least 20 132-pound bombs. Four people died – two US sailors, an oil tank captain, and an Italian journalist. More than 40 servicemen and civilians were injured.

So shocking was the unprovoked attack that many expected Washington to declare war then and there. Had it done so the Panay’s place in history might not have been eclipsed by the events of four years later.

But historians say the sinking of the Panay was a seminal event nonetheless, one that helped turn the tide of American opinion in a conflict seen by some academics as the beginning of World War II in Asia – and one that strains relations between Tokyo and Beijing to this day.

It also sowed the seeds of Japan’s destruction in the global conflict that was to come, helping spur the massive increase in US naval spending that funded the very warships that would eventually put an end to Japan’s imperial ambitions.

Indeed, some historians say that to fully understand that day of infamy in Pearl Harbor, one must first understand what happened to the USS Panay.

This is its story.

While it’s common in America to think of World War II as starting with Roosevelt’s declaration the day after Pearl Harbor, elsewhere in the world it’s viewed it as starting much earlier. In Europe, it’s commonly considered as beginning with Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939; in Asia, many see it as stretching even further back, to Imperial Japan’s invasion of China.

All out war between the two Asian countries broke out in 1937, some six years after Japan invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria.

Having swept through Beijing and Shanghai, the Japanese Imperial forces set their sights on what was then the Chinese capital of Nanjing, where they went on to commit one of the most notorious wartime atrocities of the 20th century.

The Nanjing Massacre, in December 1937, saw Japanese troops kill more than 200,000 unarmed men and civilians and rape and torture tens of thousands of women and girls, according to the post-war Judgment of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

China puts the number of dead at more than 300,000.

“Organized and wholesale murder of male civilians was conducted with the apparent sanction of the commanders on the pretense that Chinese soldiers had removed their uniforms and were mingling with the population. Groups of Chinese civilians were formed, bound with their hands behind their backs, and marched outside the walls of the city where they were killed in groups by machine gun fire and with bayonets,” tribunal documents quoted by the United Nations say.

It was into this crucible that the Panay sailed.

The river gunboat USS Panay steams on the Yangtze River near Nanjing, China, in December 1937.

As the Japanese Imperial Army bore down on Nanjing, reports began flooding in to the US Embassy of attacks on American citizens and Chinese working for US firms. The Panay was called in to help the evacuation.

Built in a Shanghai shipyard and launched in 1927, the ship was part of the US Navy’s Yangtze River Patrol, a force set up to safeguard Western interests along the great Chinese river, and was therefore an obvious choice for the mission.

But to some, it was not an auspicious one.

As the historian Bernard Cole pointed out in the February 2000 issue of Naval History magazine, the launch of the 191-foot gunboat had stalled when it became stuck on its slide into the water. Poor quality tallow, the animal fat used to grease the skids, was blamed.

As Cole noted, “a fouled launching is considered an ill omen.” And the Panay’s luck was about to run out

Still, the 14 US and foreign civilians taken aboard the US Navy gunboat on December 11 had more immediate concerns as they headed up river.

“All of us stood and watched the burning and sacking of (Nanjing) until we had rounded the bend and saw nothing but a bright red sky silhouetted with clouds and smoke,” Norman Alley, a press cameraman aboard the Panay, is quoted as saying, in a 2012 article for Naval History magazine by Frank Roberts Jr.

But they were about to become more than merely spectators to the violence.

The next day the convoy was stopped by a group of Japanese soldiers on the riverbank, five of whom boarded the Panay with bayonets fixed.

A Japanese officer “asked where the boat was going and why, and for locations of Chinese troops. The former queries were answered, but (the American gunboat’s commander) politely refused to answer the last one. The officer then asked to search the Panay and the tankers for Chinese troops, but again was refused,” Roberts wrote in Naval History.

After a tense few moments, the Japanese troops left, but the bad omens for the Panay were building up.

That afternoon, the Japanese Imperial Navy ordered its aircraft to strike “any and all ships” in the Yangtze upstream of Nanjing, according to the US Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC).

At this point, the Panay should have been safe; Japan was fighting the Chinese, not the Americans, and US warships should have been treated as neutral, not subject to attack. To underline that point, the Panay’s commander, Lt. Cmdr. James Hughes, had taken the precaution of painting large American flags on the gunboat to prevent any mistaken fire.

Japanese warplanes dive on the USS Panay on the Yangtze River and the crew fire back.

It didn’t matter. Two waves of Japanese Yokosuka B4Y Type-96 bombers attacked the Panay and the tankers, dropping at least 20 bombs according to the NHHC, while nine Nakajima A4N Type-95 fighters strafed it with machine gun fire.

The Panay’s crew, at least one scrambling to the deck without pants, fired machine guns back at the Japanese attackers but hit none.

The Japanese bombs found their mark. The Panay’s pilot house and forward gun were destroyed. Leaks developed in its hull. Dozens of people aboard were wounded, among them Cmdr. Hughes and Lt. Arthur Anders, the Panay’s executive officer, who was hit in the throat by shrapnel. Left unable to speak, Anders – whose 4-year-old son was ashore in Nanjing – gave the “abandon ship” order writing in pencil on a blood-stained piece of paper.

The order is given to abandon ship, and crew and passengers leave the floundering USS Panay in the Yangtze River on December 12, 1937.

As its crew took motorboats to the riverbank, they continued to come under fire. Behind them, the USS Panay settled in the Yangtze.

Three men died in the attack – the Pany’s storekeeper First Class Charles Lee Ensminger, Standard Oil tanker captain Carl H. Carlson and Italian reporter Sandro Sandri – with coxswain Edgar C. Hulsebus dying later that night. Forty-three sailors and five civilians were wounded.

It was the first US Navy vessel lost in action since World War I and the first ever to be sunk in combat by an aerial attack, Roberts wrote. And in the course of its sinking, according to the Heritage Flight Museum in the US state of Washington, Anders had become the first US naval officer to order “open fire” on Imperial Japanese Army troops.

Taking on water due to damage from Japanese bombing, the USS Panay sinks into the Yangtze River.

As word of the sinking reached the White House, influential voices were calling for revenge.

Navy Secretary Claude Swanson argued that war with Imperial Japan was inevitable, so best to fight while Tokyo was still stretched trying to occupy much of China, according to an account by Douglas Peifer in the November 2018 International Journal of Naval History.

Or as Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. reportedly put it to a subordinate: “They’ve sunk a United States battleship and killed three people….You’re going to sit here and wait until you wake up in the morning and find them in the Philippines, then Hawaii, and then in Panama? Where would you call a halt?”

If anything, the sense of injustice was only compounded by the fact that, in a story not short of bad omens, the US ambassador to Japan, Joseph Grew, had predicted such a tragedy almost three months earlier when he complained to Tokyo of the “reckless disregard for US lives and property” its troops in China were showing.

The ambassador blamed “young, hotheaded Japanese aviators,” according to Peifer, writing in his diary that “having once smelled blood they simply fly amok and don’t give a damn whom or what they hit.”

Pointedly, he reminded Japanese officials of how the sinking of the battleship USS Maine in Havana Harbor in 1898 had sparked the Spanish-American War.

That a similar outcome to the Maine’s sinking was avoided with the Panay’s was one of those finely balanced moments on which much of history turns.

Imperial Japan, not wanting to fight the US and still needing American raw materials for its war machine, quickly accepted responsibility.

It insisted the attack was a case of mistaken identity and poor communications, despite a US Navy inquiry finding that its dive bombers – which came within 600 feet of the Panay – must have seen its US flags.

Just over two weeks after the attack, on December 25, the Roosevelt administration agreed to accept Tokyo’s offer of $2.2 million – the equivalent of $47.4 million today – to settle the dispute.

It was a decision that, within just a few days, some in Washington would begin to question.

In 1937, there was no internet, satellites or even jet aircraft. News pictures traveled slowly, on propeller-powered planes.

So it was not until December 31 that Roosevelt administration officials could gather to watch cameraman Alley’s footage of the attack that had arrived in the DC area only a day earlier.

“The mood was grim,” Peifer wrote.

Alley had captured the full scope of what had befallen the Panay and those aboard it. His footage showed the Japanese planes bearing down on the gunboat, the crew firing back, the bloodied wounded abandoning the Panay, the ragged group of survivors moving inland to avoid further Imperial Japanese attacks and find help for their wounded.

And at the end they saw the coffins of the dead Americans loaded on a rescue boat, covered by the American flag.

In commentary added later, a narrator says, “The Panay survivors will never forget those hectic, horrible hours when American blood was shed by war-crazed culprits.”

Newsreel footage shows the survivors of the USS Panay aboard another gunboat on the Yangtze.

The images were enough to reignite calls for war by some in the Roosevelt administration, but ultimately there was little appetite for conflict in 1937 America. Isolationism was the more popular sentiment of the time.

“There were a few demands that the Fleet should be sent at once to the Orient. There were many more demands that we should withdraw completely from China,” Roosevelt’s secretary of state, Cordell Hull, later wrote in his memoirs.

While Washington stepped back from the brink, the attack on the Panay would come back to haunt the Japanese military years later, after the US joined World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Imperial Japan’s actions in China, including the sinking of the Panay, spurred the Roosevelt administration to push the Naval Act of 1938, which mandated a 20% increase in the size of the US fleet, boosting spending by an estimated $1 billion ($21.4 billion in today’s money).

Among the ships that amount bought was the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, the ship that launched the Doolittle Raid – the first US bombing raid on Tokyo – and helped turned the tide of the Pacific war in America’s favor at the Battle of Midway in 1942.

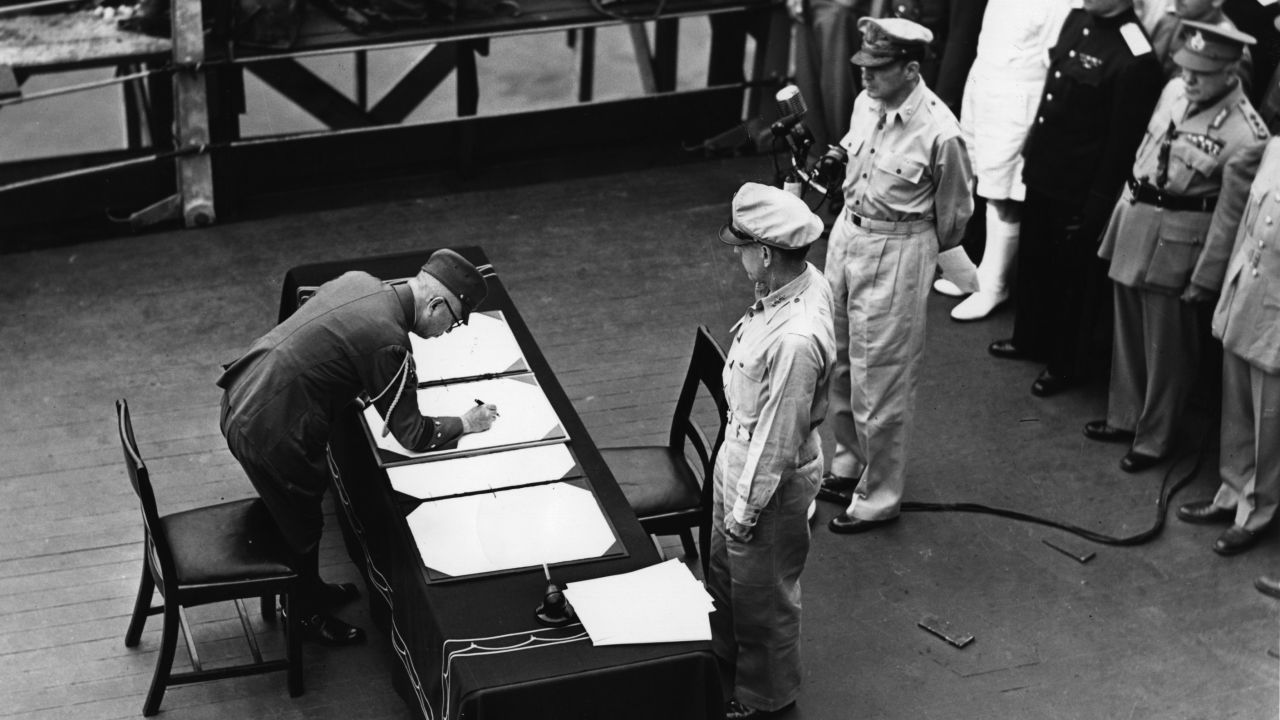

The boost also funded three Iowa-class battleships, including the USS Missouri, the ship on which Imperial Japan’s leaders formally surrendered to the allies in Tokyo Bay in 1945.

Then there are the many personal legacies, among them that of William Anders, the 4-year-old ashore in Nanjing as his father was shot in the throat. He grew up to graduate from the US Naval Academy, becoming a pilot and later an astronaut. In 1968, he became one of the first three men to orbit the moon on Apollo 8.

Meanwhile, more than 80 years after the Panay’s sinking, while the ship itself has become a footnote of US history for most, the wartime event in which it played a part remains a seminal piece of Chinese and world history and continues to color Sino-Japanese relations to this day.

China has made clear that the atrocities of that time will not be forgotten. In 2014, it designated December 13 – the date Nanjing officially fell to the Japanese – as a national memorial day. And in more recent years both its state media and government officials have drawn parallels between the massacre and the US atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945.

But there is also another, perhaps more hopeful sense in which the legacy of the Panay endures.

While the events of that time may never be completely forgotten, hidden deep in the archives are the first green shoots of forgiveness that made possible the eventual rapprochement between the US and Japan – two countries that now describe themselves as among the strongest of allies.

Those green shoots can be found in the Japanese public’s response to the Panay’s sinking. Unlike the questionable excuses offered by Japanese government officials, many responded with heartfelt sympathies.

Ambassador Grew said the US mission in Tokyo was “deluged by delegations, visitors, letters, and contributions of money,” all expressing regret and remorse on behalf of Japan and its military, according to a 2001 report by Trevor Plante in Prologue, the magazine of the US National Archives.

The outpouring illustrated what the US envoy called “two Japans,” one that represented the horrific scenes in Nanjing and the other the average citizen, according to Plante.

“That side of the incident, at least, is profoundly touching and shows that at heart the Japanese are still a chivalrous people,” Grew wrote in “Ten Years in Japan,” his book on his time as ambassador.

Plante quotes one letter in particular, from a 13-year-old girl:

“We want to tell you how sorry we are for the mistake our airplane[s] made. We want you to forgive us. I am little and do not understand very well, but I know they did not mean it. I feel so sorry for those who were hurt and killed.”

Video from Universal Studios