Lilian Echanerry said she had been struggling financially for nearly five months when she started having trouble making her rent payments last June. The mother of three had been using a Section 8 rental subsidy since 2020, when she was forced to move from her Newport News, Va., public housing at Ridley Place, a complex with more than 250 units that was torn down this past spring.

Until June, the voucher helped cover her costs, but then her rent rose beyond what she could afford.

“I’m trying to make it every day with my kids, with keeping my bills — trying to keep myself together,” said Echanerry, who added that she had struggled to find anyone who could reliably help her solve her financial problems.

Under a neighborhood redevelopment program that required Ridley’s residents to find other housing during the years-long construction of new mixed-income properties, Echanerry was supposed to have access to help navigating her relocation and other challenges that arose. But she said she was often promised assistance that never materialized.

Provided by Echanerry

“Every time I speak to people, they’re like, ‘Well, you have to wait,'” Echanerry said.

“People say they’re going to help, but they’re not helping because they’re saying one thing and doing another,” she added. Echanerry has been frustrated over the last few years by setbacks, like her inability to have a consistent case worker from the redevelopment program who would be accountable for helping her to figure out how to sign up for classes and find a job.

Echanerry’s case illustrates the challenges faced by cities across the U.S. in managing and balancing the needs of the poorest communities, as the federal government tries to remake public housing and improve their standard of living.

Ridley Place bordered the predominantly Black southeast neighborhood of Newport News. The nearly 70-year-old public housing complex had fallen into disrepair and was overrun by crime by 2019. Residents who grew up there decades ago remembered a time when it was a safe place where children could play.

“Every day we were out in the fields playing football, baseball, just having a good old time making due with what we didn’t have and just having a good time growing up,” said former resident Quinton Washington.

In recent years, most of Ridley Place’s residents were Black single moms with young children who made under $8,000 a year, according to the HUD grant application. Former residents complained their apartments were moldy, roach- and rat-infested and leaky. Outside, they said they had lingering fears about crime at their doorsteps. A former tenant told CBS News she hesitated to allow her daughter to play outdoors because she said there had been instances where people were shot just outside her front door.

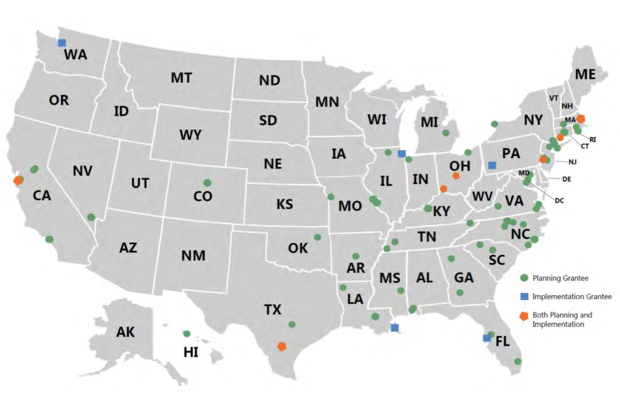

In 2019, prospects for Ridley Place and its immediate surroundings seemed more promising after the area was selected for $30 million in redevelopment funds under the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative (CNI), a program funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The initiative, which has grown to more than 40 programs nationwide, aims to rebuild communities by revitalizing public housing and assisted living.

The city planned to relocate more than 600 residents from Ridley Place, tear down the complex and replace it with mixed-income housing and offer residents the opportunity to come back when construction was completed. But a key part of the HUD program was supposed to address what happens to residents during the interim period while new housing is built, a phased process that in some cases could take up to seven years or more. Funding and local resources were set aside to help residents like Echanerry obtain services from organizations around the community to ease their transition, including transportation, childcare, food, health care, legal counseling, workforce preparation and job placement.

Correspondence between the city and HUD, however, revealed that although the grant was awarded to Newport News in May 2019, Ridley Place residents continued to struggle, even though the development program was supposed to provide support for them.

Hampton Roads Community Action Program (HRCAP), the regional non-profit group tasked with coordinating support as a lead partner on the redevelopment program, bills itself on its website as a community action agency that has been working to improve the lives of residents in Southeast Virginia for more than 50 years. But it seemed to have fallen short in offering much to improve the lives of Ridley Place residents. The city and housing authority ultimately replaced HRCAP, informing HUD that they did not believe that “Ridley Place households are receiving the services and support that they need to achieve greater economic and housing stability.”

HRCAP declined to comment.

Communities receiving a Choice Neighborhoods Initiative grant must allocate a portion of the $30-million grant for a “people plan” — programs and services for residents who must move out during the redevelopment phase. Cities establish partnerships with local organizations to augment a network of services for displaced residents and designate a “people lead” to coordinate this effort. Cities are then required to report metrics to HUD quarterly that show how residents are benefitting from these services.

According to Newport News’ housing authority, while it was in charge of the “people plan,” HRCAP was allocated nearly $1.5 million in federal and local funding to coordinate support services. In-kind donations and funding valued at more than $40 million were also made available for “People Resources,” according to documents obtained by CBS News. The housing authority said that although HRCAP did not have control over that $40 million in cash, goods and services, it did have oversight of organizations it partnered with to provide services.

Key initiatives included job training and educational attainment. However, the housing authority said it found evidence that few residents had enrolled in workforce development programs, and that children were suffering from failing grades and poor test scores.

CBS News learned that other cities across the U.S. have also had challenges with the supportive services arm of the “Choice Neighborhoods Program.” Over the last decade, at least six other Choice Neighborhoods cities have replaced the lead organizations providing similar services to residents. A HUD spokesperson conceded that communities sometimes change these contractors and the agency is supportive when grantees make changes to ensure better outcomes for the residents.

Documents obtained by CBS News show that the Newport News Redevelopment and Housing Authority (NNRHA) grew concerned about the accuracy of data from HRCAP about how much help Ridley Place residents were getting for their transition.

Questionable Data and Service Hurdles

Karen Wilds, NNRHA executive director, wrote a letter to HUD on behalf of both Newport News and the housing authority in September 2021 requesting the removal of HRCAP as partner. In the letter, Wilds expressed concern that HRCAP hadn’t accurately counted the number of Ridley Place residents eligible for and receiving support services.

In emails with city employees, Newport News’ housing authority criticized the data provided by HRCAP.

“I am not confident that HRCAP has the capacity to provide credible data through CNI’s system,” CNI manager Lynne Caruth wrote in an email in July 2021. While Caruth thought some efforts could be made to improve, she said the data had already been faulty for over a year at that point. “The People Plan data has been inaccurate since the first report in April 2020,” she said.

Wilds also complained that the non-profit had been lax about formalizing partnerships with the local providers who had committed millions in-kind donations and funding to support residents.

Wilds and a spokesperson for the city of Newport News said that a thorough review was conducted over “many” months before the decision came to remove HRCAP.

The housing authority also told CBS that no formal complaints were made about how it had managed HRCAP.

Latoya Breckenridge, a community volunteer who has worked on the Newport News project, said she and other volunteers who advised the city on the project were skeptical of reports from HRCAP about jobs programs and services it claimed to be providing because they were encountering residents who said they were struggling with unemployment and eviction. But she doesn’t blame this entirely on HRCAP.

“If the city wasn’t receiving that information from HRCAP, the city is still responsible,” Breckenridge said.

Like Brekenridge and community liaisons, Yugonda Sample-Jones, a former HRCAP employee who was also a volunteer consultant to the city on the project, said she grew concerned about the condition of residents as she witnessed alleged mismanagement of the program as HRCAP continued in its role as the “people lead.” Sample-Jones said she expressed her concerns to HRCAP executives, the housing authority and Newport News soon after she began working for the nonprofit in 2019.

screen grab, drone video

Following news of HRCAP’s removal, she provided a letter to CBS she wrote to supporters of the project, denouncing HRCAP’s leadership and alleging grant funding had been used for “superfluous purchases, like new furniture, laptops, new technology and leased vehicles,” instead of support programs like equipment needed for a health clinic.

“There was a strategic recklessness in how this project was implemented by the lead organization of the People Plan,” wrote Sample-Jones. She also said that in her exposure to HRCAP’s inner operations and “[t]hroughout [her] time with HRCAP,” she said she “witnessed, in my opinion, egregious, predatory behavior from the executive leadership.”

She said that although the city’s housing authority provided a facility to open a wellness center to give residents access to basic health care services, like blood pressure screenings and diabetes management, healthcare partners who agreed to provide aid were “impeded”in these plans to serve the community. HRCAP executive leadership failed to offer clinic hours that were flexible enough for the residents to make use of the center, Sample-Jones said. Fitness programs were undermined by “lack of support and refusal to purchase basic physical fitness equipment.” And, she said medical student interns who could provide basic wellness checks for residents were denied access to the clinic.

Three former HRCAP employees, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, complained of poor management by HRCAP. They said case workers were left to manage themselves because the department lacked supervision, gatekeeping and poor coordination of support programs either kept residents on waitlists or created layers of needless bureaucracy. “We have all of these people wanting to help us but because we were so poorly managed, it just wasn’t effective,” said one former employee.

CBS News asked HRCAP CEO Edith White and COO Kevin Otey in an email about claims made by the housing authority, city and former HRCAP employees, and they declined to comment. The housing authority told CBS that the nonprofit did not appeal or challenge its termination from its lead role.

A HUD spokesperson defended the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative, noting in a statement that over $5 billion in public and private funding has been invested “across the 40 historically disinvested Choice Neighborhoods communities.” The department also pointed out that because of the program, over 16,000 residents in those 40 communities are receiving case management, and over 10,000 new mixed-income housing units have been constructed to replace distressed HUD-assisted housing.” HUD also recently increased the budget for the initiative to $379 million.

Susan Popkin, a fellow at the Urban Institute and a leading expert on public housing redevelopment programs, said “Choice” programs require intensive case management and sometimes agencies can struggle with that because of the deep level of social work it takes to help all residents succeed, which often takes more funding than what’s provided. “It’s possible to deliver very intensive services. But it requires being strategic and having good service partners to work with. And [in] some states and some cities, [it] may be easier to do that than others.”

Both Breckenridge and Sample-Jones said they couldn’t get answers on how many residents were impacted. The housing authority did not confirm to CBS the number of residents affected by alleged shortcomings in Wild’s letter to HUD when it requested to remove the nonprofit. However, based on information obtained by CBS, all of the residents had already left Ridley Place, according to dates provided by the housing authority, by the time HRCAP was removed. Following HRCAP’s removal, the housing authority reported establishing communication with a majority of the residents.

The city and housing authority also believed that HRCAP would still have a role in serving former Ridley Place residents. “HRCAP has a long history of service delivery in the community, and we believe some of its services may continue to benefit our residents,” a city spokesperson. “Thus, we optimistically anticipate maintaining them as a partner within our more extensive network.”

Though the pandemic created some challenges, Wilds said it wasn’t the underlying cause of the disruption in services. “We just felt that we could — we needed to be dealing with the people plan a little bit differently so that we were supporting our families as much as possible with this whole process,” said Wilds. Residents were assisted by the Department of Health and Human Services until Urban Strategies, Inc., a national non-profit operating 15 other “choice” programs across the U.S, officially took over support services to residents last May.

“I just want to do better”

Dr. Amy Khare, research director at the National Initiative on Mixed-Income Communities (NIMC) at Case Western Reserve University, conducted a study on a similar 2011 program in Chicago.

Khare said that because residents are already facing the relatively sudden loss of their housing, if they aren’t receiving the transition support they need, it can chip away at their overall confidence in the program.

“I would be most concerned about transition in services for residents who had not only a disruption in their housing because they were forced to move out of their housing, but then they had a disruption in the kinds of ongoing supportive services intended to help them stay stable,” said Khare.

“That disruption in human support can lead to residents again not trusting and questioning whether or not these programs are ultimately really meant to benefit them,” she said.

Sample-Jones also said that given the long history of disenfranchisement and neglect of the residents and the community in southeast Newport News, the alleged mismanagement of the support services makes her wonder whether residents who experienced the worst of poverty would be willing to come back and take advantage of the newer housing, higher standard of living and improvements in the surrounding neighborhood.

“We felt like the program was really going to change the fabric of the system and address real barriers,” said Sample-Jones, who now says she at least hopes the changes to the people program will mean more improvements for former Ridley residents.

The Newport News housing authority said residents have already been told about the first new buildings which are being advertised to lease if they want to return. They would be moving into two of the first new apartment buildings, which are outfitted with a dishwasher, in-unit washer and dryer, central air conditioning, a fitness center and on-site management and maintenance.

At this point, Echanerry has lost much of her faith that the HUD program will ultimately benefit her.

“I just feel like the whole system with this Ridley [Place] thing is screwed up because they want to help you,” she said. “But then they don’t want to help because it’s a wait.”

She’s still frustrated about all the times she tried to find someone to help her find a job, sign up for classes and adjust her rent payments over the last two years. For her, “waiting” is not a tenable option. “I have goals that I’m trying to accomplish. And I don’t want to be struggling,” said Echanerry. “I just want to do better.”

This story was published with the support of a fellowship from Columbia University’s Ira A. Lipman Center for Journalism and Civil and Human Rights.