- The National Archives is underfunded, overwhelmed and not keeping up with technology, analysts say.

- Problems at NARA make it likely many former president have classified documents.

- Efforts by current and former U.S. officials and watchdogs to fix the system have mostly gone nowhere.

The Biden and Trump classified document revelations are very different, even though both indicate U.S. national security could have been put at risk by sensitive government documents stored in unsecured personal locations.

But they do have one similarity, security analysts tell USA TODAY: Both cases underscore how the U.S. system of safeguarding classified presidential documents is in urgent need of improvement, especially during the critical period when one administration hands over the White House keys to another.

The massive volume of records generated or used by the president, vice president and their large National Security Council staff are among the most closely held secrets in the U.S. government. Some would constitute a “grave threat” to U.S. national security if left unsecured or stored in places where they could potentially fall into the hands of America’s adversaries, according to U.S. intelligence guidelines. Some could disclose such things as the names of U.S. undercover spies and covert operations. Others could divulge the nuclear weapons capabilities of U.S. allies and enemies.

Biden’s congressional antagonists heading into 2024:Biden’s most vocal Republican antagonists emerge from the sidelines – with subpoena power

Yet problems with safeguarding such documents have been known for years, if not decades. And current and former government officials, security analysts and private watchdog groups have been pushing for reforms, with little success.

“We’re really seeing an existential crisis at the highest levels of government, at the presidential level,” said Lauren Harper, the director of Public Policy and Open Government Affairs at the nonpartisan National Security Archive in Washington, D.C. “And it’s something that we’ve certainly been saying needs to be addressed and reined in.”

Adds Scott Amey, general counsel for the Project on Government Oversight, “I’d bet you that if they go back to all of the living presidents and root through their homes and their libraries and their warehouses and garages, they’re going to unearth some classified documents there.”

Fact check:Biden did have the authority to declassify documents as vice president

5 key questions about Biden documents:What we still don’t know about Biden’s documents

Security lapses are not uncommon

Former President Donald Trump’s problems stem from his insistence that he declassified entire boxes of documents, his resistance to returning them and the fact top secret materials were mixed in with personal items. President Joe Biden’s lapses appear more accidental, his staff has said, and involve a smaller cache of classified documents from his time as vice president that was found at a former office and at his home in Wilmington, Delaware.

The White House has refused to comment on the nature of the Biden documents, including why the documents were in his possession for such a long period of time without anyone noticing. But CNN, citing a source familiar with the matter, reported that among the items discovered in a private office last fall were 10 classified documents, including U.S. intelligence memos and briefing materials that covered topics including Ukraine, Iran and the United Kingdom.

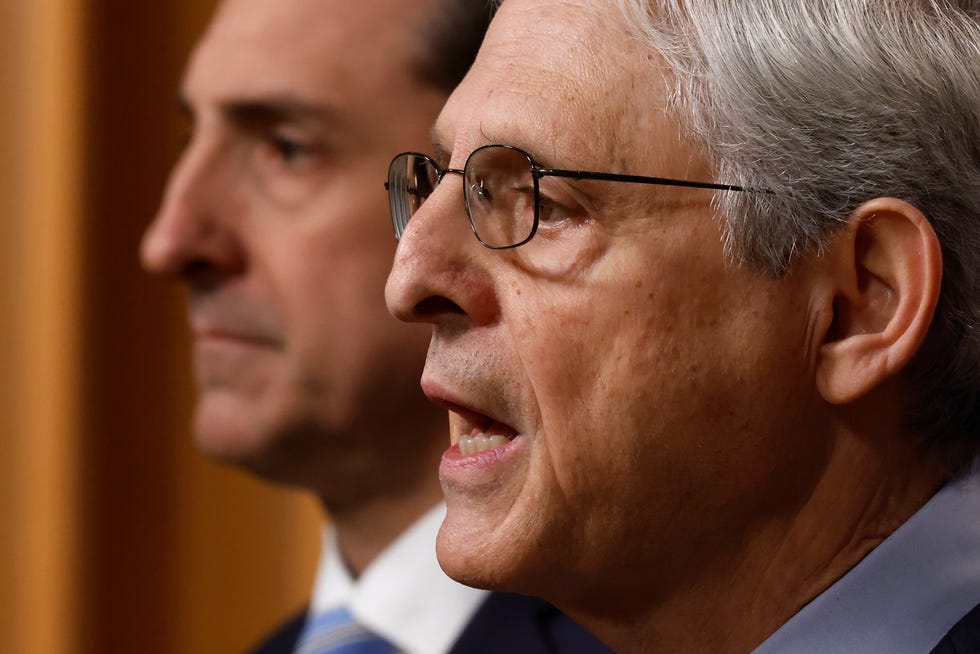

Attorney General Merrick Garland has appointed two special counsels, one each to investigate Trump and Biden to see if any laws were broken and to look for additional documents that may be in their possession.

Such security lapses are a somewhat regular occurrence, according to one former senior security official involved in protecting classified presidential documents under Trump and his predecessor, Barack Obama.

A few times a year, a current or former White House official would alert authorities about a classified, secret, or confidential document that had turned up somewhere, and someone with the appropriate security clearance would be dispatched from the White House, National Archives, or FBI to retrieve it, said the official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss matters under investigation. It happens frequently enough, he said, that the National Archives and Records Administration, as it is formally known, has formal written procedures for how to deal with it.

More:Classified documents were mingled with magazines and clothes at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago club

Mark Zaid, a lawyer who specializes in the handling of classified information, said such lapses date back to World War II or earlier, and are far more common than is known publicly.

“Before the Presidential Records Act was enacted during the Carter administration, these guys brought classified records home all the time,” Zaid said. “I have one in my library from the Truman administration that was top secret until 1994, but it was in the possession of Truman’s chief of staff for half a century, at home somewhere because that’s what they all did.”

The Presidential Records Act of 1978 was enacted after the Watergate scandal, in which former President Richard Nixon tried to claim that his secret White House tapes and other records were his personal property. It states that “the United States shall reserve and retain complete ownership, possession, and control of Presidential records,” but critics have said it’s too vague in terms of what the law covers.

“Since the PRA got enacted, pretty much every presidential library and administration, Republican and Democrat, have had instances where classified information, unfortunately, was taken home or to an office,” Zaid added. “That’s not to condone it or excuse it because it has potentially serious consequences for an individual who is found to have mishandled classified information. But it happens all the time.”

Longstanding calls to fix the problems

The Project on Government Oversight is one of several watchdog groups that have been pushing for reforms, including more funding and authority for the National Archives so it can be more aggressive about keeping current and former administrations in line.

“I’d love to see Congress turn their attention to the more systemic problems here and propose fixes on what we need those (presidential) offices to do,” Amey told USA TODAY, “as well as the National Archives, to make sure that classified materials don’t leave, either in computers or in banker’s boxes.”

The National Security Archive, a research and public interest law organization that is not affiliated with the similar-sounding government agency, said the problems with safeguarding classified U.S. documents have been made much worse due to the relatively new explosion of new forms of digital and electronic information used by presidents and their staffs.

More:5 key questions we still don’t know about Biden’s documents

At the end of each administration, Harper said, the law requires that all of those documents be sorted, cataloged and handed over to the National Archives for processing. Depending on their level of secrecy, most eventually will be made available to the public, either at the National Archives in Washington or at the libraries of former presidents.

“Even without these kinds of extreme examples from the White House, given the sheer volume of electronic records that are being created, it is a disaster that gets worse, literally, by the day,” Harper told USA TODAY.

The U.S. government’s top secrecy czar agrees.

In his latest annual report to the president, which is required by Congress, the head of the National Archives’ Information Security Oversight Office warned of the “dire need” to revamp the entire system of protecting secret government records. That includes addressing problems created by the new forms of electronic records, as well as the longstanding issue of over-classification of millions of documents that probably don’t need to be marked top secret, oversight office Director Mark Bradley wrote in the July 22 report.

Those problems, combined with the damaging effect that COVID-19 pandemic had on the work of the National Archives’ offices in recent years, means “we can no longer keep our heads above the tsunami of digitally created classified records,” Bradley wrote.

“It will be a mammoth task to turn these tidal waves,” Bradley concluded. “It will require leadership, doggedness, money, new technology and an unwavering commitment in the face of embedded resistance” to reforming the system.

More:Trump’s handling of documents proves ‘toothless’ records law needs a jolt, critics say

“He is absolutely right, and in my experience, he is not one prone to hyperbole,” Harper said of Bradley, who just retired after 30 years at the National Archives, the CIA and other security posts.

In her role at the National Security Archive, Harper issued a report in March 2022 concluding that despite all of its problems, annual funding for the National Archives is minuscule – roughly $320 million. She found the National Archives’ budget “has remained stagnant in real dollars for nearly thirty years” when adjusted for inflation, despite the vast increases in the amount of information it is required to safeguard.

When leaving office, the administration of George H.W. Bush transferred over 20 gigabytes of electronic records to its presidential library after leaving office in 1993, while Obama’s administration had thousands of times more, at about 250 terabytes, Harper’s report said.

Presidential transitions: A last-minute frenzy

One of the biggest structural problems with the way presidential documents are safeguarded is that each administration needs to use them until the very end of their term, and then has just a few weeks, or less, to pack them up for transfer to the Archives, according to Archives guidelines and documents. During that time, potentially hundreds of White House employees must pack up their things and separate their personal documents – physical and electronic – from those that need to go to the Archives for safeguarding and, in some cases, eventual declassification.

That was especially the case with Biden when leaving the Obama administration given the flurry of last-minute meetings – and overseas trips – he undertook to try and cement the duo’s legacy, former staffers told CNN and the New York Times.

“My thinking right now is it probably wouldn’t be a bad idea for someone to convene a group of experts to sit down and review the process,” said Larry Pfeiffer, a longtime CIA official who also ran the Obama administration’s White House Situation Room.

“Are we doing everything we absolutely can do to minimize the risk of this material ending up where it’s ending up?” Pfeiffer asked. “My guess is there are probably things that could be improved upon.”

Damage assessments

Law enforcement and intelligence officials continue to do damage assessments to see whether U.S. national security was compromised by the Trump and Biden documents being stored in places where they might be accessed by America’s adversaries.

Historically, many security experts say, far too many documents have been over-classified – often market top secret when they are not – which makes the task of safeguarding the nation’s real secrets even more difficult.

Pfeiffer said that the recent controversies involving both Biden and Trump have likely prompted others to see if they have any documents in their possession that need to be returned. Unless it can be proven that they took, or kept, them intentionally, he said, most cases are handled administratively and without involvement by criminal investigators from the FBI or Justice Department.

In a 2022 report issued after the Trump documents became headline news, the independent research arm of Congress urged lawmakers to consider potential reforms to the way the National Archives handles presidential documents.

The report, by Congressional Research Service analyst Meghan Stuessy, noted that the Presidential Records Act does not provide a deadline for the physical transfer of records materials, even though it does provide for a transfer of legal responsibility for materials to the archivist of the U.S., who leads the National Archives.

Also, the Congressional Research Service report said, “Congress may consider whether National Archives has sufficient ability to oversee the management of presidential records during a presidency and whether White House staff are sufficiently trained on segregating presidential records from personal records.”

And it recommended that Congress “may also consider additional legislation or oversight on the presidential records transfer process at the conclusion of an Administration. Congress might also assess the relationship between National Archives and DOJ with regard to investigations of records removal and if either entity is helped or hampered by their joint relationship” as currently required by law.

A ‘gentleman’s agreement’

One problem with the current system is that despite its responsibilities in safeguarding presidential documents, the National Archives has very weak oversight powers when it comes to the White House due to the traditional authorities granted to the executive branch of government, Harper said.

Another institutional shortcoming, Harper said, is that the Presidential Records Act “is basically a gentleman’s agreement, where a presidential administration will say, ‘Look, this is the demarcation between my personal and public records. And I will definitely give you all records that are meant to be public, and I’ll do so in a timely fashion.”

“But it has a lot of holes in it,” she said. “And it really took somebody like Trump to kind of shine a giant spotlight on exactly what those holes are.”

There’s also a little-known Presidential Transition Improvement Act that says that six months before a presidential election, the White House needs to establish an agency-level council with the National Archives to make sure that the director of each government agency is prepared to oversee the orderly and responsible transition from one administration to the next and ensure that all records management requirements are being met.

But it doesn’t apply to the White House itself, due to longstanding separation of powers policies.

More:Trump Mar-a-Lago home in Florida searched by FBI in probe into handling of classified documents

One solution, Harper said, would be for Congress to add wording to the Presidential Records Act directing the White House to voluntarily comply with the requirement and get ready to hand over all relevant documents, even if the current president doesn’t think they are going to lose a reelection bid.

“What we saw with the Trump transition was that there was actually absolutely no preparation, and no due diligence done for any of these records management principles,” Harper said. “You can’t force it, but this would put them on notice that there are things that they could be doing prior to an election to ensure that records don’t get lost and that they are handled appropriately.”

Also, she said, if the Archives had more authorities, including requiring periodic updates from the White House, it would know before the end of an administration if the president and their staff were taking the appropriate steps to safeguard their documents.

That likely would not have mattered in the case of Trump, whose refusal to turn over documents prompted the National Archives, FBI and Department of Justice to repeatedly try to get them back, analysts said. Ultimately, a judge approved a search warrant and an initial tranche of documents was seized by authorities in an early morning search.

“Obviously, there are differences here, including that Biden had some miscellaneous documents versus all of Trump’s banker’s boxes,” said Amey. “But I do think that the big question here, and where I’d love to see a congressional investigation turn to, is how much of a systemic problem is this? And what are the fixes to ensure the classified material isn’t getting out into the world?”