Deep in New Hampshire’s North Country, a handful of civic-minded Americans in a small town called Dixville Notch gathered late into the night on Monday to cast the first votes of the state’s 2024 primary, continuing a decades-long tradition that has surprising roots.

Former U.N. ambassador Nikki Haley received all six votes.

“A great start to a great day in New Hampshire,” Haley said after the votes were counted. “Thank you, Dixville Notch!”

The six registered voters in the unincorporated township — four Republicans and two independents, who also make up the entirety of the area’s population — had to cast a ballot before the votes could be counted once midnight struck, a process that typically takes just a few minutes.

Journalists and media outlets from around the world descend on the town every four years to witness the proceedings, hoping to divine some insight that might foreshadow the statewide results that will come into focus less than 24 hours later.

“We get our 15 minutes of fame every four years,” said Tom Tillotson, the town moderator, a post he’s held since 1976.

The tradition represents a marquee moment for the state, kickstarting the first primary in the nation in true Granite State fashion. But the future of the practice could be in doubt as the town’s population hovers near the minimum number of residents needed to keep it alive.

Where is Dixville Notch, and how did the tradition start?

Dixville Notch is in New Hampshire’s Great North Woods Region, just 20 miles southeast of the Canadian border. Its remote location played a role in developing the tradition of voting at midnight on the day of the presidential primary.

But the practice of late-night voting didn’t start in Dixville Notch. Another remote New Hampshire township, Hart’s Location, began voting early on primary day in 1948 to accommodate the irregular schedules of rail workers, according to the Associated Press. The practice stuck. (Hart’s Location was the inspiration for a thinly veiled episode of “The West Wing” in 2002 about a New Hampshire town called “Hartsfield’s Landing” that voted at midnight.)

Neil Tillotson, Tom’s father and his predecessor as town moderator, is credited with bringing the tradition to Dixville Notch. In 1954, Neil Tillotson moved to town and bought a local hotel, which he renamed The Balsams Grand Resort Hotel.

Eventually, he grew tired of driving 45 minutes, often in the snow, to reach the nearest polling station when it came time to vote. Tom Tillotson said his father first heard of the midnight voting process from an AP reporter. He and other residents banded together to ask the New Hampshire legislature to approve Dixville Notch as a standalone voting precinct.

“It’s an unincorporated township, and at that point, it wasn’t authorized to do anything,” Tom Tillotson said. “It was just a piece of land.”

In 1960, it was official, and the town held its first midnight vote.

“They got together, nine people, and voted at midnight,” Tillotson said. “I don’t think there was much press coverage that first year … but that started the tradition.”

Every presidential primary since, the late-night vote tallying has continued, even during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Erin Clark/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

While Dixville Notch wasn’t the first town to hold a midnight vote, the hotel was largely responsible for propelling the community to fame. The Balsams had the infrastructure — space, phone lines and a dark room — for reporters and photographers to produce and send out their stories and pictures.

“That infrastructure was much better than any of the other little towns, who basically met in somebody’s home, and for that reason, I guess the media that did cover it found it more convenient to cover Dixville than the other little towns,” Tillotson said.

This year, the two other locales known for the midnight vote — Hart’s Location and Millfield — aren’t expected to hold their votes at the late hour, due in part to aging populations that make midnight voting increasingly difficult.

The process of casting and counting votes can take a matter of minutes. Five voters are needed to serve as election workers and administer the vote. The town is allowed to count its tally before the rest of the state under a rule that says a polling place can close once every registered voter has cast a ballot.

“That’s the only reason why they can report their results so early,” said John Lappie, a political science professor at Plymouth State University. “If even one registered voter in the community doesn’t play ball, then you can’t announce the results shortly after midnight, like they do.”

For Tillotson, he says the tradition is something he “grew up on.” The process his father began in Dixville Notch is now broadcast live around the world every four years.

“It’s different. It’s not the same as everybody voting, because I do it in front of potentially millions of people,” he said. “But that being said, it’s an honor.”

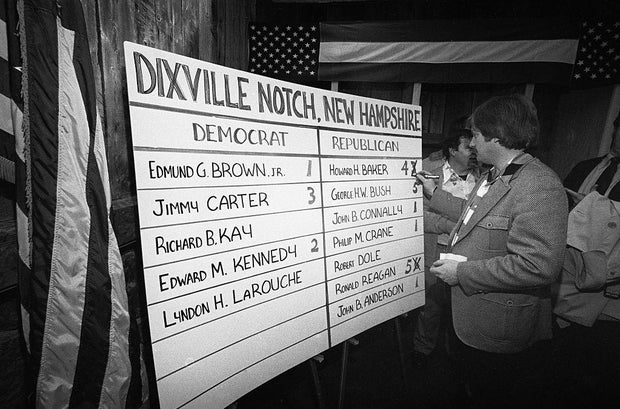

Who has won Dixville Notch in the past?

Bettmann / Getty Images

On the Republican side, pundits and observers have taken note of Dixville Notch voters’ historic tendency to side with the eventual GOP nominee, a trend that began in 1968 and persisted with startling accuracy in every presidential primary until 2012.

But the voters have also been out of step with the broader electorate, especially in years with competitive Democratic primaries. In 2020, Michael Bloomberg won Dixville Notch with three write-in votes, while Bernie Sanders and John Kasich picked up the most votes in 2016.

Those looking for signals of how the statewide electorate is feeling about the candidates would do better searching elsewhere, Lappie said.

“It’s such a small sample size that if they’ve happened to get the candidates correct so often, that’s just a coincidence,” he said. “And Dixville Notch certainly isn’t representative of all New Hampshire.”

What is the population of Dixville Notch?

Central to the tradition is the community’s size. Since it got its start in 1960, the voting bloc swelled to 37 people at its peak in the 1980s. Ahead of the election in 2020, with just four anticipated voters, a dispute arose about whether the process could move forward.

“It was unclear whether or not that was enough people to hold an election,” Tillotson said.

But after one developer decided to move back to the area, Dixville Notch was allowed to proceed with five voters. This election cycle, they’ve added another new resident.

“We actually have six,” Tillotson said. “Population boom.”

What’s the future of the tradition?

For New Hampshire, the midnight voting tradition is deeply rooted, and emblematic of the state’s broader identity as a first-in-the nation primary contest that turns out large portions of Granite Staters every four years.

“The thing about New Hampshire is we’re a small, relatively cheap state to compete in. We’re a place where retail politics actually works,” Lappie said. “New Hampshire is a state that gives an underfunded underdog a place they can actually hope to compete in.”

Every election cycle, Dixville Notch’s residents wonder whether their midnight tradition will continue in four years, Tillotson said, as the population of registered voters hovers just above the minimum needed to administer an election.

But Tillotson explained that the biggest obstacle toward continuing the tradition would actually be if the town’s population swelled. And with the redevelopment of its hotel underway, there’s a chance the effort could be “too successful,” bringing in dozens of new residents.

“As you grow, it gets exponentially harder to get 100% participation,” Tillotson said. “The herding cats syndrome kind of sets in.”