Washington — Time is running out for House Speaker Kevin McCarthy to find a compromise to keep the federal government running and avoid a costly shutdown.

Republican infighting between moderates and the hard-right has paralyzed the House from passing a short-term funding bill, which is necessary to keep the government open beyond Sept. 30, when funding for federal agencies runs out.

A temporary funding measure proposed Sunday by members of the Main Street Caucus and House Freedom Caucus includes an 8% cut to agency budgets, excluding the Defense Department and Veterans Affairs.

Hard-right members swiftly announced their opposition to the measure and have threatened to oust McCarthy as speaker if their demands aren’t met. The bill would also be dead on arrival in the Democratic-controlled Senate, which must also approve funding in order to keep the government open.

McCarthy said Wednesday he would keep the House in session on Friday and Saturday as he tries to find a resolution.

Here’s what to know about what happens during a government shutdown, and what the prospects are for avoiding one this time:

What is a government shutdown?

AFP PHOTO/Emmanuel Dunand

Many federal government agencies are funded annually by a dozen appropriations bills that need to be passed by Congress and signed by the president before the start of the new fiscal year on Oct. 1. These are often grouped together into one large piece of legislation known as an “omnibus” bill.

When Congress does not meet that deadline, the government must fully or partially shut down, depending on which agencies have their annual funding approved. Lawmakers usually buy themselves more time by passing what’s known as a continuing resolution, which temporarily extends current funding levels to keep agencies functioning while they work to reach an agreement on new spending.

The Constitution says the Treasury Department cannot spend money without a law authorizing it. Under a statute known as the Antideficiency Act, agencies are required to cease operations — with certain exceptions — in the absence of funding authorized by Congress. The act, which was first passed in 1870 and has been updated several times since, also prohibits the government from entering into financial obligations without congressional sign-off.

“Treasury cannot pay out any money if there’s not a law providing for who gets the money,” said Matt Glassman, a senior fellow at the Government Affairs Institute at Georgetown University. “If those annual bills expire, then there is no law appropriating money for certain functions.”

What happens during a government shutdown, and who is affected?

Marie D. De Jesus/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images

In a shutdown, the federal government must stop all non-essential functions until funding is approved by Congress and signed into law. Each agency determines what work is essential and what is not. Members of Congress make that determination for their own staff, as well.

“No money can come out of Treasury whether you’re essential or not essential. But who can keep working and incur obligations, even when there are no appropriations — there are three exceptions,” Glassman said.

Those exceptions are defined by the Antideficiency Act. They allow the government to fund operations to protect human life and property, and keep officials involved in the constitutional process on the job, like the president, his staff and members of Congress.

All active-duty military members, many federal law enforcement officers and employees at federally funded hospitals are considered essential, along with air traffic controllers and Transportation Security Administration officers.

Essential employees, even though they continue to work during the shutdown, are not paid while the government is shut down. They receive back pay once funding is restored to their agency. Employees in nonessential positions are furloughed until the government is funded again and don’t come into work or get a paycheck. Under a 2019 law, however, they’re guaranteed to receive back pay once the shutdown is over.

During a 16-day partial shutdown in 2013, roughly 850,000 federal employees out of a total of 2.1 million were furloughed at some point, according to the Office of Management and Budget.

What is open and closed during a shutdown?

It depends on what appropriations bills have been enacted. Any agency that has its funding approved would operate as usual. Some programs that rely on fees for their funding also continue.

As it stands now, none of the 12 annual appropriations bills have been passed, meaning a shutdown would impact every corner of the federal government.

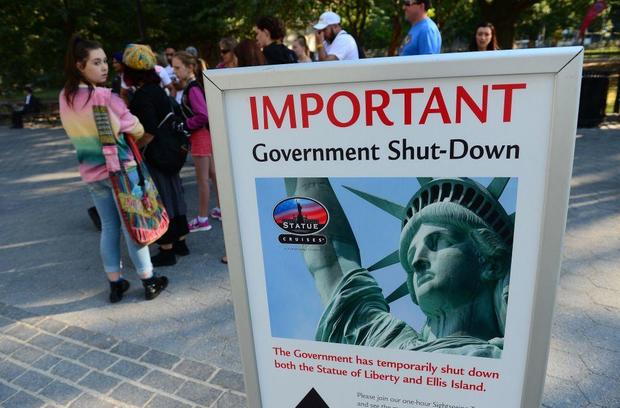

Depending on how long a shutdown lasts, national parks could close. Passport processing, hiring of new government employees and research at the National Institutes of Health could stop. Constituents’ interactions with congressional offices could also be curtailed. The White House maintains a list of links to agencies’ contingency plans in the event of a shutdown that can be found here.

Services like the Postal Service and entitlement programs, including Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, are not halted during a shutdown because they are funded through permanent appropriations that don’t require renewal. Entitlement payments keep going out, but staffing levels at the agencies could be affected and cause delays in enrollment or other service interruptions.

“Any type of interaction you’re having at a customer service level with the federal government could definitely be affected,” Glassman said.

Maya MacGuineas, the president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, said the public may not even notice the effects if the shutdown is short-lived.

“The truth is, most people won’t really feel much of a difference,” MacGuineas said. “If you’ve got a vacation planned to a National Park, you’re going to be [upset] and disappointed. But most people will go on with their everyday lives and interact with the government the same way they do and not feel a big difference. That could get worse, the longer it lasts.”

When was the last government shutdown?

The last government shutdown stretched from December 2018 until January 2019, when congressional funding for nine executive branch departments with roughly 800,000 employees lapsed.

The five-week partial shutdown cost the economy $11 billion, according to a Congressional Budget Office report. The CBO said most of that would be recovered once the shutdown ended, but estimated a permanent loss of about $3 billion.

Businesses across the country that relied on government customers reported a slowdown in business and some said they had to lay off employees. Tens of thousands of immigration court hearings were canceled. Government contractors struggled to feed their families and pay their bills.

Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

The shutdown stemmed from a standoff over President Donald Trump’s demand for $5.7 billion to fund a wall along the border with Mexico. Trump had vowed to close the government if the funding wasn’t included in spending legislation, but Democrats refused to give in.

Trump conceded after insisting for weeks that he would not reopen the government without money for the wall, signing a bill to reopen the government for three weeks while Congress negotiated a spending deal.

Three weeks later, Trump signed a compromise spending bill to avert another government shutdown, ultimately accepting a bill that did not meet his $5.7 billion demand for his long-promised border wall.

What was the longest government shutdown?

Since 1976, when the current budget process was enacted, there have been 20 funding gaps lasting at least one full day, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Before the 1980s, it was common for the government to continue operating like normal when funding bills hadn’t been passed, Glassman said. But in 1980 and 1981, Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti issued two opinions that said it was illegal for the government to spend money without congressional approval.

“Since then, there have been some funding gaps that have been relatively short — two or three days — and then there have been three long ones that are politically significant, all stimulated by Republicans,” said Roy Meyers, political science professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The 2018-2019 shutdown over Trump’s border wall funding lasted 34 full days, making it the longest shutdown in U.S. history.

Before that, the record was 21 days in 1995 and 1996, when President Bill Clinton refused to bend to steep spending cuts and tax reductions proposed by House Speaker Newt Gingrich. Public opinion was on Clinton’s side and Republicans eventually caved, Meyers said.

There wasn’t another shutdown until 2013, when Republicans used budget negotiations to try to defund the Affordable Care Act. With efforts to gut the new health care law backfiring, Republicans gave in and the government reopened after 16 days.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell acknowledged on Sept. 19 that public opinion has not sided with Republicans during previous shutdowns.

“I’m not a fan of government shutdowns,” McConnell said. “I’ve seen a few of them over the years. They never have produced a policy change and they’ve always been a loser for Republicans politically.”

Will the government shut down this time? When?

It seems likely. With just days to go until the Oct. 1 deadline, time is running out for McCarthy to find a solution that could pass both the House and the Senate and be signed into law by President Biden. Both chambers would need to move quickly to pass an identical continuing resolution to extend funding at current levels and keep the government open.

Republicans’ razor-thin majority in the House means McCarthy has little room to maneuver, given the staunch opposition from hard-right members who are demanding dramatic cuts in spending. If McCarthy moves forward with a bill that can attract Democratic votes, he faces the prospect of those conservatives trying to oust him as speaker, a dynamic arising from concessions he made to win the speaker’s gavel in the first place.

Yet McCarthy has seemed optimistic that a shutdown could be averted.

“It’s not Sept. 30. The game is not over. So we continue to work through it. I’ve been at this place many times before. We’re going to solve this problem,” he told reporters on Sept. 20.

Ellis Kim and Jack Turman contributed reporting.