Washington — Since the indictment charging him with 37 federal felony counts was unsealed last week, former President Donald Trump and some of his allies have repeatedly mischaracterized a law known as the Presidential Records Act, according to legal experts and the federal agency charged with preserving White House records.

“Under the Presidential Records Act, I’m allowed to do all this,” he wrote on Truth Social after the indictment was revealed, referring to his decision to retain dozens of boxes of documents and other material from his time in the White House. He repeated that claim in a speech in Georgia over the weekend, calling the charges a “fake indictment.”

Former Trump attorney Tim Parlatore also misconstrued the law last week, telling CNN that outgoing presidents are “supposed to take the next two years after they leave office to go through all these documents to figure out what’s personal and what’s presidential.”

Those assertions prompted a public rebuke from the National Archives and Records Administration, or NARA. The agency released a statement detailing how presidential records are meant to be handled.

“The PRA requires that all records created by Presidents (and Vice-Presidents) be turned over to [NARA] at the end of their administrations,” the Archives said.

NARA also refuted Parlatore’s assertion, saying that there is “no history, practice, or provision in law for presidents to take official records with them when they leave office to sort through, such as for a two-year period as described in some reports.”

A federal grand jury in Florida charged Trump with 31 counts of willful retention of national defense information and six other counts alleging he illegally concealed documents and obstructed the Justice Department’s investigation. The former president is expected to plead not guilty during his first court appearance on Tuesday.

Trump is not charged with violating the Presidential Records Act, which has no enforcement mechanism. But his repeated invocation of the law has renewed questions about what it says and how it applies to government documents. Here is a look at the federal law that lays out the requirements for maintaining and preserving presidential records:

What is the Presidential Records Act?

Enacted in 1978, four years after President Richard Nixon’s resignation, the Presidential Records Act established that presidential records belong to the U.S. government, not the president personally, and must be preserved.

The law governs records of the president, vice president and certain parts of the Executive Office of the President, such as the National Security Council and the Council of Economic Advisers. It lays out the requirements for the maintenance, access and preservation of information during and after a presidency.

Records that must be preserved include documents relating to certain political activities and information relating to the president’s duties, including emails, text messages and phone records. Excluded from the act’s requirements for preservation are a president’s personal records, or documents of a “purely private or nonpublic character.”

“Presidential records are records in the White House relating to the constitutional, statutory or other official or ceremonial duties of the president,” Jason R. Baron, the former director of litigation at NARA, previously told CBS News. “Personal records such as diaries, journals or other personal notes that are not prepared or used or communicated for government business are excluded from the definition of what constitutes a presidential record.”

The Trump indictment indicated that the boxes found at Mar-a-Lago included “newspapers, press clippings, letters, notes, cards, photographs, official documents, and other materials.” But personal records are supposed to be separated from official material before a president leaves office, and the outgoing president is responsible under the law for immediately handing over all his official records to NARA.

Who has custody of presidential records?

While in office, the president has responsibility over the “custody, control and access to presidential records,” according to a 2019 report from the Congressional Research Service.

But after a presidency, that responsibility moves to the archivist of the U.S., the top NARA official who is required under law to make the former president’s documents available to the public “as rapidly and as completely as possible.”

Since presidential records are U.S. government property, a former president has to receive permission from the archivist to display presidential records, such as in a presidential library, which are operated and maintained by the National Archives, according to the report.

In its recent statement, NARA said that Trump, unlike other former presidents, “did not communicate any intent to NARA with regard to funding, building, endowing, and donating a Presidential Library to NARA under the Presidential Libraries Act,” the law governing how official records can be used in presidential libraries.

The agency also clarified that former President Barack Obama, who also declined to endow a presidential library, did not take presidential records to Chicago upon leaving office.

“When President Obama left office in 2017, NARA took physical and legal custody of the records of his administration in accordance with the Presidential Records Act,” the agency said. “NARA made arrangements to move the roughly 30 million pages of paper Presidential records of the Obama administration to a federally acquired, modified, and secured temporary facility that NARA leased in Hoffman Estates, IL, which meets NARA’s requirements for records storage and security.”

The Obama Foundation agreed to help pay to digitize those records and move them to another NARA facility once it decided against building a traditional presidential library, the agency said. Obama is building a privately funded presidential center that will not have archival storage.

What does the Trump indictment say about how he handled records?

Jon Elswick / AP

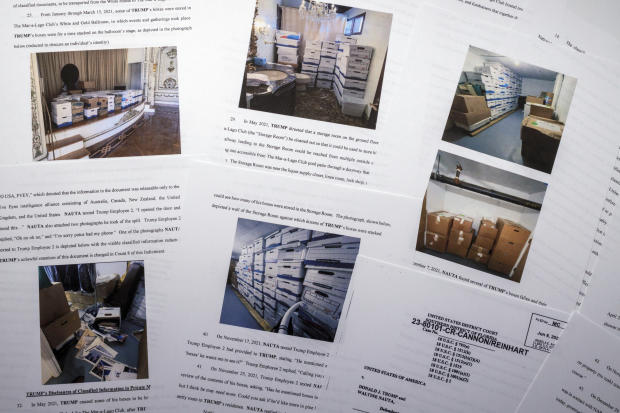

According to the indictment, Trump ordered dozens of boxes of records shipped to Mar-a-Lago as he was preparing to leave office. “Hundreds” of classified documents were eventually found mixed in with other records in some of those boxes, which were kept at various locations throughout the property.

“After his presidency, TRUMP was not authorized to possess or retain classified documents,” the indictment said.

Starting in May 2021, NARA “repeatedly demanded that TRUMP turn over presidential records that he had kept after his presidency,” the indictment said. “On multiple occasions, beginning in June, NARA warned TRUMP through his representatives that if he did not comply, it would refer the matter of the missing records to the Department of Justice.”

Under increasing pressure from the Archives to hand over the material in late 2021 and early 2022, the indictment said Trump personally reviewed the contents of some of the boxes. In January 2022, two Trump aides loaded 15 boxes to transfer them to NARA.

Fourteen of those 15 boxes were found to contain classified documents, according to the indictment, and NARA soon referred the matter to the Justice Department. The FBI opened a criminal investigation in March 2022, and a federal grand jury was convened the next month.

The grand jury issued a subpoena for any remaining records in May 2022. The indictment alleged that Trump and a co-conspirator hid many boxes from a Trump attorney who searched the property for records, ultimately causing another attorney to falsely certify that all official records had been located.

The FBI eventually executed a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago in August 2022 to recover any other documents that had not been turned over. Agents found 102 documents with classified markings during the search, the indictment said.

How is the Presidential Records Act enforced?

The Presidential Records Act includes no enforcement mechanism, and a former president has never been punished for violating the law. But other federal statutes impose penalties for illegally retaining or distributing national defense information.

Prosecutors are not relying on the PRA to bring charges against Trump. He is instead charged with retaining national defense information under a different law known as the Espionage Act, a 1917 statute that has been used to prosecute other high-profile cases related to the retention or dissemination of classified information.

The indictment alleged that Trump had documents relating to U.S. nuclear programs, military plans, communications with foreign countries and other matters in some of the boxes he kept at Mar-a-Lago.

The former president is also charged with three counts of withholding or concealing documents in a federal investigation, two counts of making false statements and one count of conspiracy to obstruct justice. Those counts are focused on his actions in response to the government’s efforts to retrieve the documents from Mar-a-Lago.

For his part, Trump has denied any wrongdoing and has characterized the investigation and prosecution as politically motivated.