CNN

—

Geoff Butler jumped into his truck in the dark hours of July 11 as heavy rain battered the rural Vermont town of Johnson.

Just moments earlier, at roughly 2 a.m., he and his wife, Caroline, received a starting phone call from a friend who urged them to check on their small clinic, the Johnson Health Center. The clinic was just yards away from a river, where waters had begun to rise.

By the time Geoff arrived, water was filling the parking lot and quickly creeping toward the clinic’s backdoor. With a friend’s help, he carried out a fridge full of vaccines and moved medical supplies to higher cabinets and countertops.

The nonprofit clinic, which opened its doors just eight months earlier, had quickly become a safe haven for the community. It offered not just primary care in the middle of a rural medical desert, but also essential treatment for substance use disorders, from medication to case management and other recovery services. And it was soon expecting to receive the state’s first ever vending machine for Naloxone, a medicine which can quickly reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.

To the Butlers, the clinic was a dream come true after a big leap of faith: They sold their home in the state capital of Montpelier to move an hour’s drive north to Johnson and poured their life savings into turning the old Subway store they rented into a welcoming space for their patients.

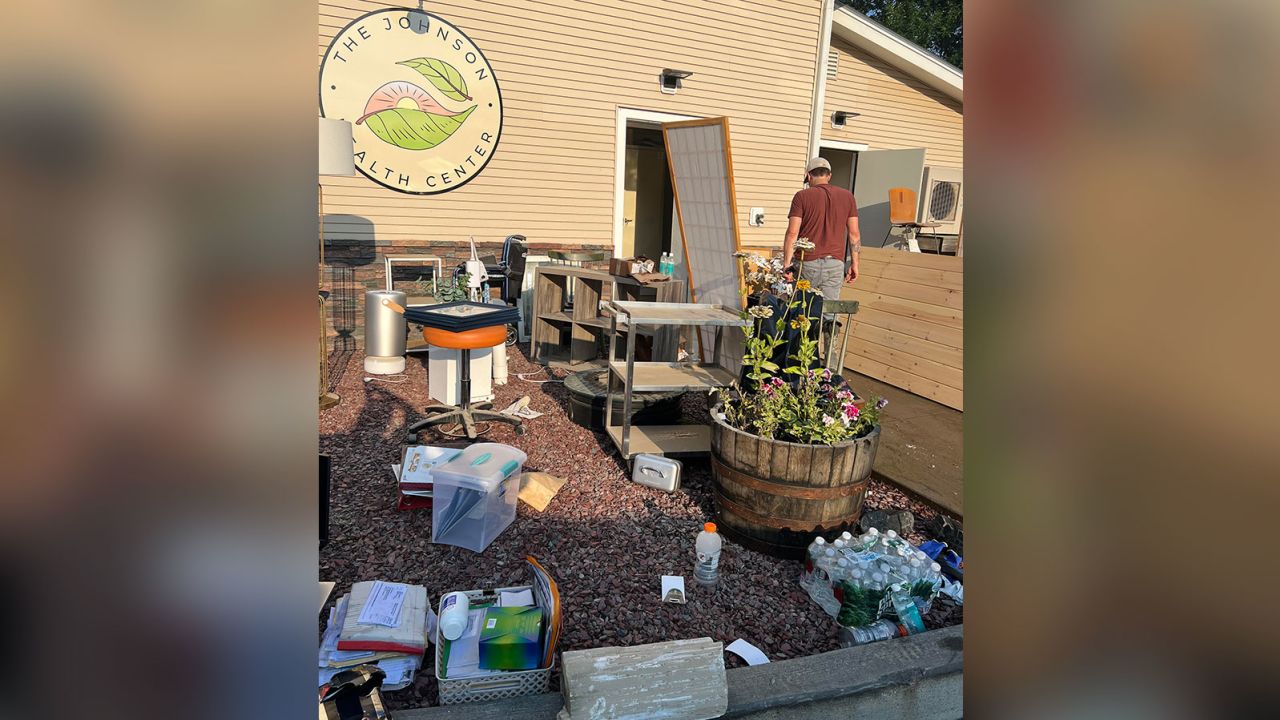

By the time Geoff returned to the clinic around 5 a.m. that day, nearly everything inside was destroyed. Floodwater and waste reached up to the health center’s windows. Computers and other electronic devices had been soaked, medical supplies were strewn about, microscopes rendered useless, and furniture was turned upside down and ruined.

“We put everything that we had into that practice, financially,” Caroline, a nurse practitioner, told CNN. “So I was completely devastated when I saw it because I just knew there was no way that we could do this again.”

But that’s exactly what they’re now determined to do.

More than a month since the devastating floods swept Vermont, the Butlers have spent their days cleaning up debris and drying out the building, often alongside patients who showed up to help. And all the while, they’ve continued their work, operating out of a small office in the back of a community center and with the help of telehealth appointments. But repairs and replacements of all they’ve lost will cost tens of thousands of dollars, the Butlers say. A GoFundMe in support of the center had raised roughly $23,000 as of Saturday morning.

Lamoille County, where Johnson is, was among the hardest hit parts of the state, with dozens of people who needed to be rescued and homes turned unlivable. The clinic remains among the community’s toughest losses, and the need for its services is evident a month on.

“We’ve actually seen an increase in our addiction services, we’ve had more walks in the last month than we’ve had in a while,” Geoff told CNN in an early August interview.

“I didn’t realize how impactful the work was that we did, how many lives we’ve touched,” he added. “We’ve just got to keep pushing for them. We’re just going to keep on doing what we do best. And that’s helping people.”

When Caroline first began operating out of a small room at a central Johnson building, the future looked uncertain in their new hometown. She worked early mornings and long nights, while Geoff, who is a certified recovery coach, worked in construction to help keep the family afloat.

In their free time, they’d chip away at clinic renovations, installing new flooring and adding personal touches in every corner: parts of an old bowling alley that helped bring together the reception space, a bright barn door that led to a waiting area, a coffee station, paintings from the home they sold, and decorations with motivational phrases like, “follow your dreams,” tucked in the corners. It quickly began to feel like home.

“We put quite a bit of sweat equity into it,” Geoff said. “Within the population that we work with, a lot of folks have had some trauma around medical care. To try and break down that trauma and break down the stigma that they felt in the past, that’s one of the biggest pieces that we were trying to provide for people: a safe and welcoming place to get medical care.”

The Johnson Health Center opened its doors in November 2022 and tended not just to the town’s residents, but people in substance use recovery who came in from across the state. Caroline particularly wanted to help normalize the use and easy access of Naloxone, keeping the medicine in parts of the office patients could easily access.

The drug has proven highly effective at reversing opioid overdoses, but experts say it remains largely under-distributed across the United States. A 2022 study suggested increasing access to naloxone, in combination with other recovery initiatives, could have a “substantial impact on the overdose epidemic” in the country.

The year before that study was published, Vermont saw the largest increase in overdose deaths of any US state, rising a staggering 85% between March 2020 and March 2021, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics.

The idea for a vending machine that’s available to residents 24/7, Caroline said, followed the fatal overdose of a 17-year-old boy roughly two miles from the clinic. He was one of more than 230 people who died of fatal overdoses in Vermont last year.

In the eight months the clinic was open, it went from treating roughly 36 patients to nearly 300 in July.

Among them, 45-year-old Robert Bishop, who, after battling addiction for more than three decades, met Caroline while she was working for an addiction program close to the border of New Hampshire. The pair worked together for about a year, before Caroline left for Johnson. Bishop followed her there.

In the time since, Bishop says Caroline has been a lifeline, connecting him with employers, giving him phone credits when he couldn’t afford any, arranging for transportation and helping him navigate medication prescriptions. “She’ll randomly text me on a Sunday … and say ‘Hey Robert, how’s everything going? Are you doing alright? Do you need anything?’” Bishop said. “I’ve never had a doctor do that.”

It’s not just Bishop. The clinic’s patients can reach Caroline or Geoff any hour of the day; – most have their cell phone numbers. It’s helped tremendously: “She has kept me sober, she most likely saved my life,” Bishop said.

“Honest to God,” he said in a phone call with CNN after the floods. “If I had the money, I would rebuild that office … Just because I know how many people it’s helped.”

The clinic is part of a larger effort for recovery services that’s taken shape in the heart of Johnson. Most of that is the work of nonprofit Jenna’s Promise, a partner of the health center. The organization was founded by the family of Jenna Tatro, who died of an opioid overdose in the winter of 2019. She was 26 – and about to mark two months in recovery.

The organization has developed a more holistic model of recovery services around town, focused on housing, workforce development and reducing the stigma around substance use disorders. It includes recovery housing; a community center with workspaces and events including yoga and weekly recovery meetings; a discount store for goods and appliances; and a coffee house that employs individuals in recovery.

Gregory Tatro, Jenna’s brother, told CNN accessing health professionals who meet people exactly where they are in their recovery is a key part of the process. It’s why the health center is so critical.

“They have devoted all they are, all they hope to be to this idea that we can change things,” Tatro said of the Butlers. “They’ve lowered the barrier and they made connections with people, which I think is the cure to this epidemic that we have of loneliness and that, oftentimes, spirals into substance use.”

Cleaning up what the floods destroyed has been a community effort.

Within the Jenna’s Promise organization, parts of a recovery housing facility and coffee shop were wiped out, with damages Tatro estimates will cost upward of $150,000.

At the health center, Caroline estimates just purchasing all the medical supplies that were destroyed will cost at least $50,000. That includes computers, printers, microscopes, laboratory equipment, specialized treatments for skin infections caused by drugs like xylazine, and even basic supplies, down to Band- aids, she said.

And then, there will be the costs of actually rebuilding their clinic.

There is good news: Though the floods delayed its arrival, the health center is expecting to receive its new Naloxone vending machine this month.

And with the help of their friends and neighbors, the two are hopeful they will create a new space – one that will be carefully planned around the potential of future natural disasters, Caroline said.

“The outpouring of community support has really been the silver lining to all this,” Geoff said. On the day after the flood, as the Butlers tried to salvage what they could from the clinic, residents and patients – some who had also faced destruction – showed up at their door to help.

“It really made us realize the impact that we’re having on the community and the importance of the work that we’re doing,” he added. “Sometimes, in the day to day, you may kind of forget that, you might not see it, but it was really apparent that day.”

So while they’re unsure of what the Johnson Health Center’s future will look like, the Butlers say they’re here to stay. The community needs – and wants – them here.