Delaware businesses aren’t expecting a respite from the staffing challenges felt across several industries last year as the COVID-19 pandemic worsens once again entering 2022.

Business owners for months have struggled to hire employees at the level of compensation they offered prior to the pandemic. In most cases, they’ve increased their baseline pay and added other benefits but are still left with openings.

“Staffing has become such an issue in every industry there is,” said Bob Older, president of the Delaware Small Business Chamber.

Delawareans exited the workforce at an unprecedented rate during the pandemic. The labor force participation rate was as much as 2% lower at times in the past year and a half compared to February 2020.

That means that even when the economy reopened in the middle of 2020, Delaware had around 10,000 fewer people employed or seeking employment.

Residents have shared a variety of reasons for leaving their jobs with Delaware Online/The News Journal, including concerns over contracting COVID-19, childcare responsibilities and overwhelming mental or physical demands.

Overall, the effects of the pandemic have driven the “costs of working” higher, says Desmond Toohey, assistant professor of economics at the University of Delaware.

MASK MANDATE RETURNS: Delaware requiring masks in most public indoor settings starting Tuesday

“The longer the uncertainty of the pandemic drags out, the worse I would expect this to be,” Toohey told Delaware Online/The News Journal this fall.

Delaware’s job numbers have improved in recent months – adding about 1,000 jobs from October to November and about 11,000 year over year, according to the most recent data – but the gap between state’s employment level and the national average continues to grow.

The unemployment rate was 3.9% in February 2020. The unemployment rate in November was 5.1%, above the national average of 4.2%.

Among the most affected sectors is leisure and hospitality. There were 4,800 fewer workers employed in the industry in November compared to February 2020, according to the state’s seasonally adjusted data.

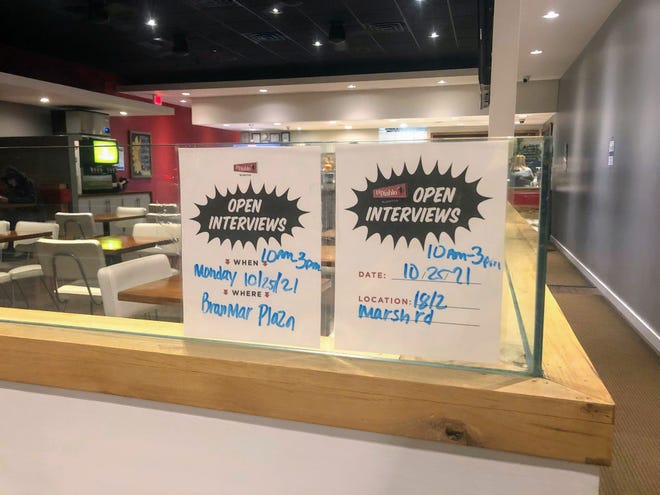

Michael Meoli, the owner and operator of more than 20 McDonalds in Delaware and the eastern shore of Maryland, said last year was “the most difficult struggle” of his three-decade career.

His company increased pay (starting wages range from $13 to $15 per hour), added flexibility to scheduling and instituted a same-day pay option to try to attract workers. Without enough employees, drive-thru waits worsened and shifts became more challenging for the workers that remained, Meoli said.

Some locations closed their dining areas or reduced dining area hours because of staffing issues. Combined with supply chain pressure, the increased wages led to increased prices.

“We have to go to the menu board at some point,” Meoli said. “We’re a value-driven business. So that is a very, very delicate process.

“We have a pretty good feel for what our customers can tolerate in terms of price increases, and we’ve got to find a way to work that with our wage structure.”

Manish Patel, manager of Wayback Burgers in Middletown, Smyrna, Milford and Millsboro, said the four restaurants have been short-staffed since the beginning of the pandemic.

They are offering higher pay and more schedule flexibility to try to compete with other employers and the applicants they do receive aren’t as qualified as they used to be.

“No one is paying minimum wage anymore,” he said. “It’s been very hard.”

Delaware’s minimum wage increased to $10.50 per hour at the start of the year. It will increase annually by more than $1 each year until reaching $15 per hour in 2025. The employers Delaware Online/The News Journal spoke with are near or at that level today.

Many pro-business groups pinned the labor shortage on the extra $300 per week benefit Congress provided unemployed workers during the pandemic. The benefit expired in Delaware on Sept. 6.

As of November, Delaware had added about 3,000 to its employment tally since September. In that time, Delaware’s hiring, however, stayed behind the national average. In states that ended the benefit early, job growth improved but not significantly, according to several analysts.

The effects of staffing shortages aren’t limited to the service industry. As they manage record-setting numbers of COVID-19 patients, the state’s hospitals have fewer workers than they did this time last year. The hospitals received a combined $25 million in federal money late last year to cover sign-on and retention bonuses that are in the thousands.

PREVIOUS REPORTING: What’s stopping Delawareans from going back to work? It’s not just unemployment benefits

Some Delaware schools last week went remote due staff shortages related to COVID-19. The governor’s state of emergency issued Monday makes it easier for recently retired teachers to become substitute teachers, a role that the state has been lacking since the early days of the pandemic.

COVID-19 testing sites have been closed in recent days for a lack of staff.

At Wilmington-based WSFS bank, high attrition in 2020 as other companies offered hybrid and remote work and increased pay necessitated a shift in how the company marketed itself to perspective front-line employees.

“Those things really started the ball moving for us and we said, “ok, how do we highlight that coming to WSFS, we are going to be flexible and you can grow your career,” Chief Human Resources Officer Michael Conklin told Delaware Online/The News Journal this fall.

The company said it saw improvements last year, but it’s still adapting. All of the bank’s branches last week started operating as drive-thru and appointment only because of staffing problems.

Toohey, the UD professor, anticipates there will be a permanent shift in labor dynamics, but the full extent of that shift will be difficult to understand until the pandemic is less of a presence, he said.

“Workers’ preferences may simply have changed so that less work and lower income is more attractive than it used to be,” he wrote. “As an economy and a society, we have gotten used to having a lot of cheap, available labor: real wages have remained constant for decades. That may not continue.”

If people work and spend less, the public will be able to support fewer businesses leading some to fail in the long term, Toohey said. In the short term, the changes will hit some harder than others as employers weigh the need to increase prices to support higher wages and their bottom lines.

“These changes will not develop evenly across the economy,” he said. “An employer that raises prices risks losing customers if the competition has not yet raised theirs. A business that could theoretically survive in the long term may struggle through the current environment as wages, employment and prices are all in transition.”

Reporter Ben Mace contributed reporting.

Contact Brandon Holveck at bholveck@delawareonline.com. Follow him on Twitter @holveck_brandon.