If you meet McKinley Phipps now, he’s a far cry from the 20-year-old, chart-climbing rapper known as Mac, signed to music mogul Master P’s No Limit Records, whose 1998 album “Shell Shocked” reached No. 11 on the Billboard Top 200. “It felt good to be a part of something that was big,” said Phipps. “It felt good to be a part of something that was recognized all around the world.”

But in an instant, Phipps’ rise came crashing down in February of 2000, when a 19-year-old man was shot and killed during an altercation at Phipps’ show at a nightclub in Slidell, Louisiana. The man later died. Detectives eventually took Phipps into custody after witnesses said he had a gun.

CBS News

“I pulled my gun out when I ran toward the door,” Phipps told CBS News. “And that was probably the biggest mistake I ever made. I would later learn that because people saw me with this gun, that’s kind of why people were, like, under the belief that maybe he did it.“

Phipps was charged with first-degree murder.

“It was all on MTV News,” he said. “I never was on MTV until I caught a charge.”

A member of Phipps’ entourage admitted to the shooting, but he says that confession fell on deaf ears.

During the trial, prosecutors zeroed in on the same lyrics that made Phipps a star.

According to Phipps, prosecutors took out of context the lyrics from two different songs and spliced them together to make a statement. “One song was ‘Murda, Murda, Kill, Kill,’ which was, like, a straight battle rap. The other one was a song called ‘Shell Shocked,’ and the line that they referred to was actually a line about my father. They said, ‘This young man said, Murder, murder, kill, kill, if you f*** with me, I’ll put a bullet in your brain.'”

A jury convicted Phipps of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

Erik Nielson, co-author of “Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America,” and a professor at the University of Richmond, said rap lyrics have been used as evidence in more than 500 cases against artists since 1991: “Not only do prosecutors cherry-pick lyrics and decontextualize them to serve their own purposes, but they often do it do it without any knowledge or understanding of rap music at all.”

The New Press

He said that, unlike other genres, “rap music is the only fictional form, musical or otherwise, that is targeted like this in the courts.”

Nielson called Phipps’ case one of the most egregious he has ever seen.

“I’m not here to tell you that somebody is guilty or innocent. I’m only here arguing for a person’s right to a fair trial,” Nielson said. “But I’ve always had one exception, and that exception is Mac Phipps.”

Former Georgia prosecutor Chris Timmons, who had no connection to Phipps’ trial, has tried more than 100 cases and has used rappers’ music videos to link them to criminal street gangs. “I didn’t use any of their lyrics,” he told “CBS Mornings.” “I didn’t feel like any of their lyrics were relevant to [a specific] robbery. But what I did use was the lyrics and the video to show that these people have a relationship.”

Timmons views using lyrics as a legal strategy.

“If you’ve got a confession, whether that confession rhymes, whether it’s set to music, you’re going to want to use it, if you’re a prosecutor,” he said. “Same thing with defense. You’re gonna want to keep it out.”

Prosecutors in Fulton County, Georgia referenced several songs in their indictment of Grammy-winning rapper Jeffery Williams, a.k.a. Young Thug, whose trial on charges of racketeering and gang activity allegedly linked to murders and theft begins this week. Williams has pleaded not guilty to all charges.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom recently signed the Decriminalizing Artistic Expression Act, which restricts the ways in which an artist’s lyrics may be used against them as evidence in court. Similar legislation, the Restoring Artists Protection Act, or RAP Act, is being proposed on the federal level.

Miko Media/Rapbay/Urbanlife

Phipps served 21 years of his 30-year sentence and was released from prison in 2021 after being granted clemency.

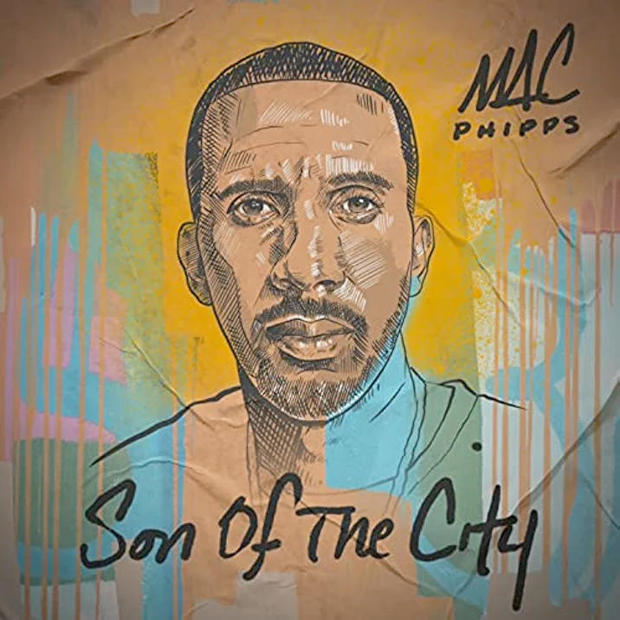

His album “Son of the City,” his first project since coming home from prison, debuted last October.

“I don’t have too many songs, if I have any, about prison life,” he said, “because the whole time I was in prison I was imagining myself free.”

Though released from prison, Phipps needs permission from a parole officer to leave Louisiana, or even stay out past 9 p.m., in order to perform or to travel across the country championing legal reform.

“I can definitely say I’m more conscious of the messages that I want to convey to the audience,” Phipps said. “I would never censor myself, but I do value my words more.”

For more info: