Ian Pisarchuk sat behind a screen and terrorized his victims.

He’d befriend them mostly online, and then the demands would start. He wanted photos of them, or said he already had them. He made threats to get what he wanted from girls and young women, using details from their social media accounts to exert power over them and get what he wanted for his own pleasure.

“Words cannot describe the anxiety Ian has caused me,” said one of his victims in a Bucks County court last month.

In 2019, Pisarchuk set his sights on the young girl, getting her to send him explicit images of herself and then threatening to expose the photos online.

Even though the victim blocked Pisarchuk on Snapchat, the online app where they communicated via short videos and photos, she was constantly worried he would make good on his threats.

The fear turned her world “cloudy” she told a judge, and she would feel no peace until Pisarchuk was arrested in June 2021.

She was one of 15 victims targeted by Pisarchuk, 27, in what prosecutors say was the first major sexual extortion, or sextortion, case in Bucks County. Pisarchuk, of Bensalem, was sentenced to 20 to 51 years last month.

For subscribers:‘He should be locked up forever’: Bensalem man gets 20 years in prison for ‘sextortion’

Another victim, Lindsey Piccone, would take her life after Pisarchuk set his online sights on her.

The state sexual extortion law has been on the books since 2020, but the criminal charge has not been widely used. Lindsey’s Law, inspired by Piccone’s death passed in 2022, upping the penalties for those convicted of sexual extortion that result in death and serious injury, but advocates still worry.

Experts say the crime is underreported, and parents and kids need to be vigilant.

“It’s a human violation to a person,” Petty Ettinger, executive director of Network of Victim Assistance Bucks County said. “Even though they’re not physically touching them.”

While sexual extortion can involve physical sexual acts, the most common form, experts say, is where the victim is contacted through forms of social media or other online communications. In the Pisarchuk case, he used Snapchat.

And cases are on the rise in recent years with the FBI earlier this year sending out a public safety alert. More than 3,000 victims were targeted in the United States last year.

“There’s so much unknown and I think that instills a lot of fear in people,” said Brianna Dion, senior victim advocate for NOVA of Bucks County.

Family pushes for legislation:‘No parent should have to bury their kid’: Family advocates for legislation after Bucks woman’s suicide in ‘sextortion’ case

Pisarchuk charged:DA: Bensalem man ‘sextorted’ nine more victims on SnapChat

What is online sextortion?

Predators looking to sexually extort someone online can typically find a victim on social media networks. They often use Snapchat, Facebook, Google Chat, WhatsApp and Instagram.

In the Pisarchuk case, he used a “friends of friend” feature to identify targets, and he knew some of the people he spoke to.

In many cases, the victims are between the 10 and 17.

Dion said the person contacting the victim usually knows them in some capacity, even if just online.

After connecting with the victim, they can develop a relationship and seem harmless at first.

Eventually they try to extort explicit images by threatening to harm the victim or their families, or to release images that they may already have. They can use things that the victim posted on social media, like family information, to bolster their threats.

Experts say those threats are very rarely carried out, but the victim’s fear is very real. And has proven deadly.

Lindsey Piccone: Sextortion leads to death

In 2016, Pisarchuk, a Kutztown University student, found Lindsey Piccone on Snapchat. Soon, authorities said, he would begin threatening her and demanding she send sexually explicit photos.

Piccone, a nursery school caregiver, would eventually yield to his demands. The next day, the Bensalem woman took her own life.

“Before someone else ruins my life, I am ruining mine,” a note read in part.

The FBI said more than a dozen sextortion victims died by suicide last year.

Advocates say the fear and anxiety that the victim, or someone they love, may get hurt, and the threat of images being exposed, keeps victims quiet. The FBI reported that victims may also be extorted for money in cases where they may have already sent an explicit image.

“These kids are still in this mentally developing age and they can’t process and handle all that,” said Stephanie Shantz-Stiver, victim advocate coordinator for NOVA.

Pisarchuk’s victims were overwhelmed and feared his next moves, authorities said.

“They lived in pretty much constant fear not knowing what the defendant is going to do,” said Bucks County Deputy District Attorney Brittney Kern.

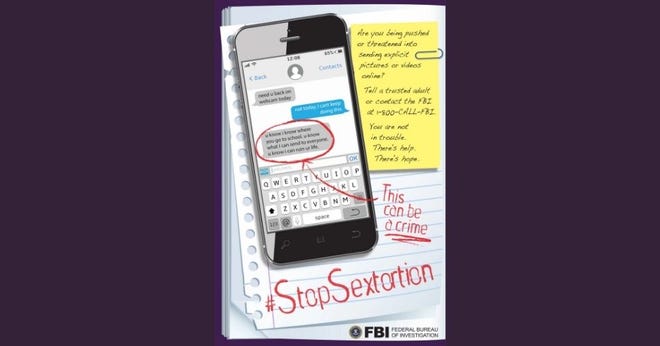

How to #StopSextortion?

Ettinger encouraged people to make sure their social media profiles are private. Without the right privacy settings, they are potentially vulnerable to being targeted.

“Your door is open the world,” she said. “And the world is open to you.”

She encouraged parents to be aware of what social media platforms their children use, and to be aware of what they are posting. Ettinger also urged understanding if their children come to them as victims of sextortion.

The stigma, embarrassment or concern of getting in trouble could be barriers to reporting a problem.

“The victim kind of feels like they are backed into a corner and they don’t really know what to do,” Dion said.

Teen victims should report threats to a parent or trusted adult, or to police. They should also not delete any communication they have received, so that authorities can investigate the interactions properly.

“If they’re deleting certain evidence it’s going to be harder for the police to figure out who is committing these crimes,” Dion said.

Kern said she’s hoping with the resolution of the Pisarchuk case that more people would be comfortable reporting potential sextortion.

“It’s never too late to report it,” she said.

Resources for parents and their children

Children who find an explicit image of themselves online may have it taken down by going here, https://takeitdown.ncmec.org.

Resources for parents me be found on the Internet Crimes Against Children Taskforce website, https://www.icactaskforce.org/internetsafety.