Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

CNN

—

Scientists are puzzling over a strange feeding technique that they think whales recently began using: The creatures swim to the surface of the ocean, open their mouths into a gaping yawn with their upper jaw sitting just below the water’s surface, and wait for hoards of fish to swim in.

The method, however, may not be new at all. In fact, it may have been observed and recorded by our distant ancestors — knowledge that was buried in ancient texts and folklore, according to a peer-reviewed study published Tuesday in the journal Marine Mammal Science.

Modern researchers have long known that whales feed by swimming swiftly with their mouth ajar toward a school of fish or krill.

But the “trap feeding” or “tread-water feeding” method, as it’s called, was first observed in 2011, scientists speculated that it might have been a new method that whales adapted because of changing ecological conditions. Or, perhaps it was only being spotted for the first time because new technologies, such as drones, are allowing whale behavior to be observed in unprecedented detail.

The study published Tuesday, however, suggests that humans recorded instances of whales trap feeding in the 13th century in Old Norse manuscripts, where the whales may have been described as a seemingly mystical being called the “hafgufa.”

“While postmedieval scholars have often confused the hafgufa with fantastical creatures such as the kraken and even mermaids, a close examination of earlier sources demonstrates that they refer to it explicitly as a ‘type’ of whale,” according to the study. “This raises the interesting and significant possibility that, rather than appearing for the first time in two species on opposite sides of the globe within the last two decades, these feeding strategies may have existed in the distant past.”

One of the most compelling examples from ancient texts was found in a document called Konungs skuggsjá, or “The King’s Mirror,” which was composed for a Norwegian king in the 1200s and was likely an attempt to compile something resembling our modern-day encyclopedias, said study coauthor Dr. John McCarthy, a maritime archaeologist in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University in Australia.

The description in Konungs skuggsjá included some outlandish elements, noting “in those instances where it has appeared to men, it has looked more like an island than a fish.” But it also included this observation of hunting habits that is remarkably similar to modern observations of trap or tread-water feeding.

“It is said of the nature of this fish that, when it goes to feed, it gives a great belch out of its throat, along with which comes a great deal of food. All sorts of nearby fish gather, both small and large, seeking there to acquire food and good sustenance. But the big fish keeps its mouth open for a time, no more or less wide than a large sound or fjord, and unknowing and unheeding, the fish rush in in their numbers. And when its belly and mouth are full, (the hafgufa) closes its mouth, thus catching and hiding inside it all the prey that had come seeking food.”

The “belch” described in that text, researchers suggested in the study, may refer to how rorqual whales filter their meals, dispelling some food to help lure more prey into their mouths. They also noted that there can be a “rotten cabbage” smell associated with whale feeding.

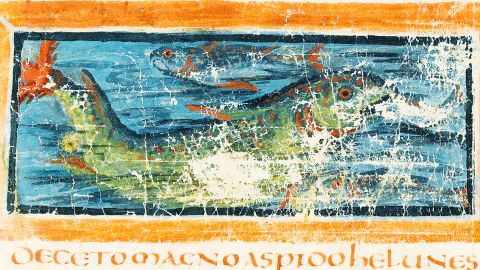

There are even earlier examples of similar descriptions that use different names to describe the “hafgufa” creature, possibly dating as far back as a Greek text composed sometime between 150 and 200 AD. Examples can also be found in Medieval Bestiaries, which were large catalogs of both real and imaginary creatures that included colorfully drawn depictions.

At the time they were complied, McCarthy noted, these texts were intended to be a serious reference work, despite the inclusion of what appears to the modern eye to be descriptions of fictitious animals.

“They could very easily have inaccurate information and alongside accurate information,” he said. “We have no more ability to discriminate between those than they did at the time, except that we now know from modern science what species actually (exist) and what’s credible or not credible.”

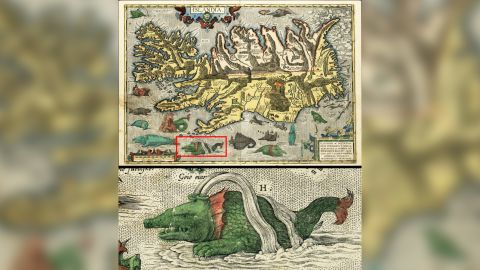

Over time, the descriptions of “hafgufa” and similar creatures may have been relegated to the world of fantasy and folklore because these early descriptions were not wholly accurate. McCarthy points to one drawing from 1658 that shows a giant sea monster with two orifices on its head spewing water. While seemingly the stuff of fiction, the drawing might simply be “someone’s misinterpretation of a blowhole,” McCarthy said.

That may be how we arrive at today’s perception of the “hafgufa” as a vague, fictional sea monster. The video game God of War Ragnarok, for example, includes a “hafgufa” that’s depicted as a giant jellyfish.

“I think the main take-home point here is just to respect people in the past as being just as intelligent as we are,” McCarthy added. “They looked at things in their best available framework. And so we shouldn’t dismiss the evidence … we should try to consider it from the perspective of the people at the time and put ourselves into their shoes.”