At Henderson’s Brewery in Toronto, two best friends, business partners for decades, have a new venture: Rush Canadian Golden Ale. And as Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson know, anything connected to their band Rush will most likely be a hit.

Fifty-five years after they formed Rush in the suburbs of Toronto, Lee is out with a memoir looking back, called “My Effin’ Life.” He said, “We all think we know ourselves, but we keep secrets from ourselves. It takes sometimes a deep dive like that to turn over all the stones and see, Wow, that was me.“

CBS News

Geddy Lee may now live a rock star’s life, with some of his 350 bass guitars lining his home studio. But it’s nothing he could’ve imagined, this son of Jewish immigrants, Holocaust survivors who’d courted at Auschwitz. “It’s a miracle I’m sitting here and able to enjoy the fruits of my life, all because they held out and survived,” he said.

His given name is Gary. “And my mom had a very thick accent, and so she said, ‘Geddy, come the house.’ That’s how my name was born.”

The life his parents’ determination provided was changed forever in eighth grade, when Lee started chatting with a kid sitting nearby in the back of the room: Alex Lifeson.

Lee noted, “We were really goofy.”

Axelrod asked, “It’s so odd when he uses the word goofy; the future rock stars are always the coolest guys in the room.”

“We wanted to be cool,” laughed Lifeson. “But we were too goofy to figure out how to do that!”

A few years later, Lifeson was on guitar and Lee on bass when they held auditions for a drummer. “And to our everlasting good fortune, a lanky, shirtless, goofy guy pulled up in a Ford Pinto and started playing triplets like machine gun rattle,” said Lee.

Neil Peart completed the lineup that would stay together for the next four-plus decades.

Rush performs “Limelight”:

Rush’s blend of musicianship, stagecraft and, yes, a little goofiness inspired intense loyalty from a crowd that was largely male teenagers in the early days. Though the 1981 album “Moving Pictures” had fan favorites like “Limelight” and “Tom Sawyer,” hit singles were never their jam. Lee notes, “We used to say, ‘Wow, that’s a catchy tune we just wrote. If somebody else played it, it might be a single, but if we play it for sure, we’ll f*** it up!'”

But they knew what they were doing, combining that big, progressive rock sound with Geddy’s distinctive voice. One critic wrote, “If Lee’s voice were any higher and raspier, his audience would consist entirely of dogs and extraterrestrials.”

“That’s a good one,” said Lee. “I’ll buy that!”

Theirs was a formula that would sell 40 million albums.

The lesson? “The lesson,” said Lee, “is be yourself and stick to your guns.”

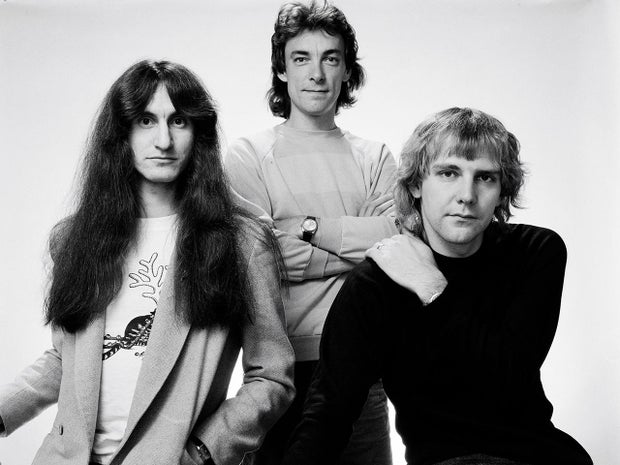

Fin Costello/Redferns via Getty Images

And that might’ve been the whole story of Canada’s most successful rock band ever. But in 1997 the music stopped. Neil Peart’s daughter died in a car crash. “It’s the worst pain, the worst possible pain, to lose your child,” said Lee.

Ten months later, Peart’s wife died of cancer. It would take five years for Peart to want to play again.

Lee said, “And we walked out on stage as three people that were really thankful that we had a second chance to do this. Rush 2.0 was a different band.”

How? “More appreciative, looser. We just started saying yes to things we normally said no to.”

Which is how they ended up in TV shows like “South Park,” and movies like “I Love You, Man.”

Lifeson also noticed a change in their audiences: “We’d see more women at our shows. Like, a lot more.”

“Yeah. Like five or six,” Lee laughed.

“But it was really interesting to see the growth of the band go from that kind of cliquey thing, culty thing to something more broader,” Lifeson said.

Frazer Harrison/WireImage via Getty Images

While they’d be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2013, tragedy wouldn’t leave triumph alone. In 2016, Neil Peart was diagnosed with cancer. He died in 2020.

Axelrod asked, “And here you two are figuring out what the next chapter looks like, and someone’s missing?”

“Yeah, said Lee. “It’s difficult to figure out what that chapter is without him.”

Asked whether they’d considered finding another great drummer to go tour again, Lee said, “Have we talked about it? Yeah. It’s not impossible, but at this point, I can’t guarantee it.”

Meanwhile, Lifeson strikes a more hopeful note. “It’s just not in our DNA to stop,” he said.

Rush fans should know, however they continue to collaborate, they’ll do it the way they always have, as Lee says: “Do what you believe, because if you do what someone else believes and you fail, you got nothing. If you do what you believe and you fail, you still have hope.”

For more info:

Story produced by David Rothman. Editor: Joseph Frandino.