NFL Hall of Famer Brett Favre hosted Mississippi officials at his home in January 2019, where an executive for a pharmaceutical company Favre invested in solicited nearly $2 million in state welfare funds, according to pitch materials obtained by CBS News.

A document distributed at the January 2, 2019 meeting describes plans to secure money from the state’s Department of Human Services, which operates Mississippi’s welfare program. The pitch was led by Jacob VanLandingham, then the CEO of pharmaceutical company Prevacus, which was attempting to develop a concussion drug.

The effort to infuse a for-profit business venture with money intended for some of the neediest families in the nation is the latest development in a welfare fraud investigation that has been swirling around the famed quarterback, a Mississippi native, and former state officials.

Former federal prosecutor Brad Pigott, who investigated the transactions for the state, told CBS News the agreement between the state and Prevacus was “an egregious betrayal, both of the poor and of the law.”

The meeting at Favre’s Mississippi home was not his first interaction with state officials about the company. One month earlier, text messages first reported by Mississippi Today appear to show the former NFL quarterback personally lobbied then-governor Phil Bryant. The news site reported that VanLandingham offered Bryant stock in the company, and Bryant agreed to accept it after leaving office.

“It’s 3rd and long and we need you to make it happen!!” Favre wrote to the governor, according to Mississippi Today.

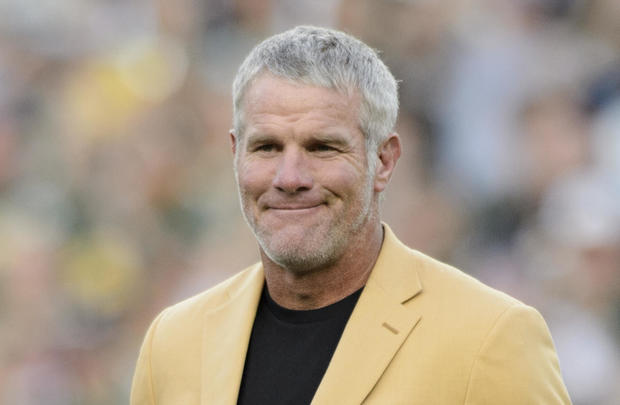

Hannah Foslien / Getty Images

“I will open a hole,” Bryant replied, a reference to the work of a football offensive lineman. Favre later updated Bryant after Prevacus began receiving state funds, according to Mississippi Today.

Eric Herschmann, an attorney for Favre, said in an interview with CBS News that state officials, including Bryant, never told Favre that the money Bryant would provide would be derived from welfare funds. Herschmann pointed out that Bryant had previously served as Mississippi state auditor, leading the department that oversees public funds.

“He knew who all the parties were involved. If there was an issue about these funds not being used, or unable to be used, he should have been the first one that stood up and said something,” said Herschmann. “He never said anything to Brett Favre, nor did anyone else ever tell him that this was restricted welfare funds.”

On January 19, 2019, VanLandingham and Zach New, an executive for a nonprofit tasked with doling out Temporary Assistance for Needy Families welfare funds, signed a contract for $1.7 million promising Mississippi that, in return for the money, it would have the “first right of refusal for clinical trial sites” in a future study phase described as “1B.” New and his mother Nancy entered guilty pleas to state and federal charges related to bribery and fraud stemming from their work for the nonprofit Mississippi Community Education Center.

Months later, VanLandhingman asked a state welfare official for the money in a text message exchange, a screenshot of which was obtained by CBS News.

“We would love 784k,” VanLandingham wrote to an employee associated with the nonprofit.

“Jake, you cannot even imagine the word stress for us right now! At any rate, we can send 400k today. I will need to let Brett (Favre) know that we will need to pull this from what we were hoping to help him with on other activities. 😩,” the employee replied, before also asking for “status reports.”

VanLandingham replied, “Thx sister. Can we stay in line to get the other 380k ? I Ly (sic) you guys.”

Pigott is a former U.S. attorney who investigated the transactions while representing the state in a civil lawsuit seeking millions from dozens of people and companies, including Favre and Prevacus.

Pigott said Favre “was the largest single outside investor” in Prevacus when it received the state grant.

“Both Federal and Mississippi law required 100% of that money to go only to the alleviation of poverty within Mississippi and the prevention of teenage pregnancies,” said Pigott, who said Prevacus ultimately received $2.1 million.

And Pigott said the grant has so far failed to live up to its promise. “They did not, as we understand it” run clinical trials of Prevacus in Mississippi, Pigott said.

Prevacus was purchased in 2021 by Nevada-based Odyssey Group International, where VanLandingham is now an executive vice president. In September, the company completed its Phase 1 clinical trial. The study was done in Australia, according to National Institutes of Health records and a September 2021 press release. The company said in a separate press release five days ago that it is moving onto Phase 2 trials.

An attorney for VanLandingham said in a letter to CBS News that VanLandingham and Prevacus were “never aware that the money received was sourced by TANF funds or that it was earmarked to help welfare recipients.”

The attorney, George Schmidt II, said VanLandingham is currently identifying potential sites for the next clinical trial, “which includes sites in Mississippi per the contract.”

Favre has previously acknowledged soliciting state funds for a volleyball stadium at his alma mater, the University of Southern Mississippi, where his daughter was on the team. Favre also repaid more than $1 million in speaking fees, for speeches that were never delivered and radio spots, paid for from the Mississippi welfare fund.

Favre said in a statement to CBS News that “I have been unjustly smeared in the media. I have done nothing wrong, and it is past time to set the record straight.”

“No one ever told me, and I did not know, that funds designated for welfare recipients were going to the University or me. I tried to help my alma mater USM, a public Mississippi state university, raise funds for a wellness center. My goal was and always will be to improve the athletic facilities at my university,” Favre said.

Neither Favre nor VanLandingham has been charged with any crime.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that then-governor Phil Bryant was among state officials in a Jan. 2, 2019 meeting at Brett Favre’s home. The story has been updated.