At the Gagosian Gallery in New York, an exhibition of Pablo Picasso’s works opened last month – one of nearly 50 shows this year in museums and galleries around the world marking the 50th anniversary of the artist’s death, from sculptures in Spain, to landscapes in Mississippi, even one exhibit at New York’s Museum of Modern Art exploring works from just one summer.

CBS News

And at Sotheby’s last month, Picasso’s “Femme à la Montre” (“Woman with a Watch”) became the most expensive painting to be auctioned this year, selling for $139.4 million.

Alexi J. Rosenfeld/Getty Images for Sotheby’s

But in the #MeToo era, the master’s reputation has also been the target of reappraisal. As the Brooklyn Museum put it: “It’s Pablo-matic.”

In her recent New York Times column, “Picasso: Love him or hate him?,” art critic Deborah Solomon raised the question whether Picasso should be reevaluated. “Why shouldn’t he be reevaluated?” she said. “We are living in a time when we no longer want to tolerate abusive behavior.

“I love the way he depicted women; I don’t feel cruelty in the paintings, I don’t feel sadism,” Solomon said. “If we are going to look at his life, that’s where all the problems come in. He obviously was a cad. He was a raging chauvinist.”

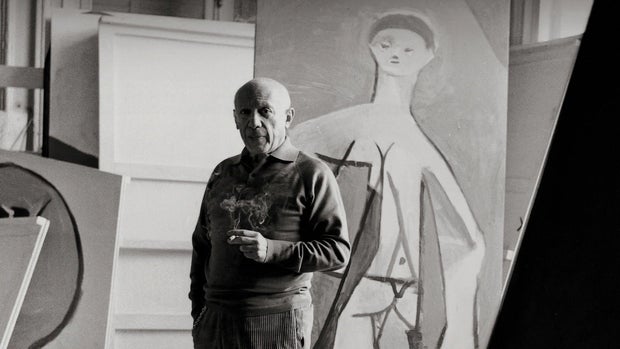

Franz Hubmann/Imagno/Getty Images

Picasso abandoned his first wife, ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova. The lover he left her for, Marie-Thérèse Walter, later died by suicide. Another lover, Dora Maar, needed shock therapy after Picasso walked out on her.

Solomon said, “There’s the famous photograph of him trailing Françoise Gilot on the beach, holding a parasol above her head. You would think he is the most helpful lover. I don’t think it really captures what he put women through.”

Gilot, an artist herself, became the only one of Picasso’s many muses to leave him. Paloma Picasso, the artist’s last surviving child, was four years old when Picasso and Gilot split. “She thought that in that relationship, they should be equal,” Paloma said.

“He didn’t like that?” Mason asked,

“Once she left, he didn’t!” she laughed.

For the next decade Paloma and her brother, Claude, would spend about four months a year with their father. “What I always thought was fascinating is that every time we arrived from Paris with Claude, the house would look different,” Paloma said. “Because he would have been maybe through a phase of doing ceramics. So, the house was filled with ceramics. You could hardly walk.”

She was aware, at that age, that she was growing up in a magical world. But in 1964, just months before her mother’s book, “Life with Picasso,” was published, Paloma says her stepmother, Jacqueline Roque, abruptly cut her off from her father. “I think that Jacqueline felt threatened by us,” Paloma said. It was, she said, very difficult to take.

A few times a year, Paloma says she went unannounced to her father’s gated house in the south of France. The response she received when ringing the doorbell was, “Monsieur n’est pas la.”

But she kept going back: “Just because I would hear that I didn’t want to see my father. So, I had to do this so that I would keep my sanity.”

Mason asked, “He could have made an effort to see you, couldn’t he?”

“Actually I did run into him once in the street. And everything was great except that Jacqueline kept pulling him, saying, ‘Oh, we have to go. Pablo, we have to go.'”

“You seem to give him a break, a lot.”

“Yes. I guess. True,” she laughed.

“You tend to blame it on the people around him, or on your stepmother.”

“Yeah. So, I’m daddy’s little girl, I suppose!”

This year, Paloma, a renowned jewelry designer, took over the administration that runs the artist’s estate. Asked about the attempts to reappraise her father post-#MeToo, Paloma said, “Before they made him into a god, which is, of course, an exaggeration. And so now he’s become this terrible monster, which is a huge exaggeration. Of course, he had some faults. But he was not nice to his men friends, either. Nobody cares about that!”

Artist Mickalene Thomas’ own series of works, “Tête de Femmes,” took inspiration from Picasso’s female portraits.

Mickalene Thomas; © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society

When asked if her view of him has changed, Thomas replied, “No, he’s still an a*****e.”

“But has that affected your respect for him as an artist in any way?” asked Mason.

“It’s complicated, and that’s okay,” she replied. “I mean, there are family members that are the same way. He was innovative, experimental. And he did it half the time in his underwear!”

But she does not think Picasso should be “cancelled.”

“I wouldn’t want my work to be cancelled,” she said. “I think it’s very complex, because right now we can separate the art from the artist, because he’s not here. But would we hold him accountable if he was?”

Solomon said, “Art is larger than this moment. And this moment is causing a lot of dissent, much of it justified. But art is larger than that.”

She said we should look to cubism – which Picasso created – to understand the artist: “What made him a modern artist is that he took on the single point perspective that had prevailed in art for 500 years – he believed that we never see things just one way.”

And she believes we should see Picasso the same way: “When we look at Picasso, he deserves to be seen from multiple perspectives. It’s okay to have conflicting feelings about him. You can say, ‘I love his work, but he was a bad boyfriend. And I’m glad I never met him!'”

For more info:

- Picasso Celebration 1973-2023

- “Picasso Sculptor: Matter and Body,” at Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in Spain (through January 14, 2024) | Virtual tour

- “A Foreigner Called Picasso,” at the Gagosian Gallery, New York City (through February 10, 2024)

- “Picasso in Fontainebleau,” at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (through February 17, 2024)

- “Picasso Landscapes: Out of Bounds,” at the Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, Miss. (through March 3, 2024)

- “Picasso: Love him or hate him?” by Deborah Solomon (The New York Times)

- Artist Mickalene Thomas

-

Credits: © 2023 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society

© RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY, photograph: René-Gabriel Ojéda

Landscape Image © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY: photo: Mathieu Rabeau

Harlequin Photo: © Metropolitan Museum of Art/Licensed by Art Resource, New York

Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and Gagosian

Story produced by Julie Kracov and Sara Kugel. Editor: Carol Ross.

See also: