Editor’s Note: Peter Bergen is CNN’s national security analyst, a vice president at New America and a professor of practice at Arizona State University. He is the author of “The Cost of Chaos: The Trump Administration and the World.” The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion on CNN.

CNN

—

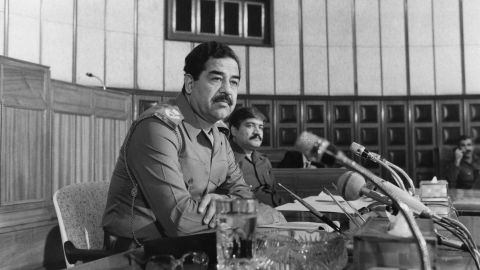

Two decades ago, on March 19, 2003, President George W. Bush ordered the US invasion of Iraq. Bush and senior administration officials had repeatedly told Americans that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was armed to the teeth with weapons of mass destruction and that he was in league with al Qaeda.

These claims resulted in most Americans believing that Saddam was involved in the September 11, 2001, attacks. A year after 9/11, two-thirds of Americans said that the Iraqi leader had helped the terrorists, according to Pew Research Center polling, even though there was not a shred of convincing evidence for this. Nor did he have the WMD alleged by US officials.

US and UK forces defeated Saddam’s troops within weeks, but an insurgency sprang up against the invaders, which persisted for years. On December 13, 2003, US Special Operations Forces found Saddam hiding in a one-man-size hole in northern Iraq.

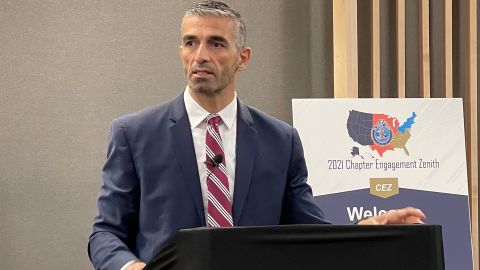

The FBI decided that George Piro, a Lebanese American special agent in his mid-30s who spoke Arabic, was the right person to interrogate Saddam. Piro’s work ethic was impressive: He would arrive at the FBI gym in downtown Washington, DC, at 6 a.m. for a workout, so he could start on the job at 7 a.m. at his office, which was lined with Middle Eastern history books.

The stakes could not have been higher for the FBI. Piro was under tremendous pressure to find out from Saddam the truth about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction and purported ties to al Qaeda. CIA Director George Tenet had famously told Bush that the case that Saddam had WMD was a “slam dunk.”

The Iraq War was also sold to Americans as a “cakewalk.” Instead, hundreds of American soldiers had already been killed in Iraq by the time of Saddam’s arrest.

The CIA first questioned Saddam. And then over a period of seven months, Piro talked to him for many hours a day, with no one else allowed in the interrogation room. He discovered from the Iraqi dictator that no WMD existed and that Saddam only had contempt for Osama bin Laden, the leader of al Qaeda.

The dictator’s discussions with Piro confirmed that the Iraq War was America’s original sin during the dawn of the 21st century — a war fought under false assumptions, a conflict that killed thousands of American troops and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis.

The war also damaged America’s standing in the world and the credibility of the US government among its citizens. Even the official US Army history of Iraq concluded that the real winner of the war in Iraq wasn’t America. It was … Iran.

After interrogating Saddam, Piro ascended to high-ranking positions at the FBI, retiring in July as the special agent in charge of the Miami field office. Now he is writing a book about his lengthy interrogations of the Iraqi dictator for Simon & Schuster.

As the 20th anniversary of the start of the Iraq War approaches, I spoke to Piro about what some consider the most successful interrogation in FBI history and the aftershocks of the US invasion of Iraq, which are still being felt today.

Our conversation was lightly edited for clarity.

Peter Bergen: Tell me how this all started.

George Piro: I received a call on Christmas Eve, at about 5 o’clock in the evening, from a senior executive in the Counterterrorism Division. And he informed me that I had just been selected to interrogate Saddam Hussein on behalf of the FBI.

Bergen: What was your reaction?

Piro: Panic. Initially — I’ll be honest — it was terrifying to know that now I was going to be interrogating somebody that was on the world stage for so many years. It seemed such a significant responsibility on behalf of the FBI. I went to Barnes & Noble and bought two books on Saddam Hussein so I could start improving my understanding of who he was and all the things that were going to be important in developing an interrogation strategy.

I had already been to Iraq once, the first element of FBI personnel to deploy, and I had begun to develop an understanding of Iraqi culture and the Baath Party, which was led by Saddam.

Saddam was born on April 28, 1937, in a small village called al-Ajwa (near Tikrit). He had an extremely tough childhood as he did not have a father, and his mother married his uncle, who became his stepfather. Growing up, Saddam and his family were very poor, and initially, he was unable to attend school, but that childhood shaped the man Saddam became.

His childhood instilled in him a deep desire to prove everyone wrong about him and not to trust anyone, but to rely solely on his instincts. As a young man, he joined the Baath Party, and one of his early assignments was to assassinate the then-prime minister. The assassination attempt failed, and Saddam was forced to flee Iraq. But upon his return, he was seen as a tough guy, an image he would promote throughout his career.

At my first meeting with Saddam, within 30 seconds, he knew two things about me. I told him my name was George Piro and that I was in charge, and he immediately said, “You’re Lebanese.” I told him my parents were Lebanese, and then he said, “You’re Christian.” I asked him if that was a problem, and he said absolutely not. He loved the Lebanese people. Lebanese people loved him. And I was like, “Well, great. We’re going to get along wonderfully.” (Saddam was a Sunni Muslim, while most Iraqis are Shia Muslims.)

Bergen: How long were you with Saddam? And, of course, you’re communicating in Arabic throughout, right?

Piro: About seven months. Initially, I would see him in the mornings. I would translate for his medical staff. And then, the formal interrogations were once or twice a week for several hours. As time went on, I started to spend more and more one-on-one time with him because I could communicate directly and very quickly with him. I built that to about five to seven hours every single day, one-on-one, a couple of hours in the morning, a couple of hours in the afternoon and then a formal interrogation session or two a week.

And we talked about everything. So especially in the first couple of months, my goal was just to get him to talk. I wanted to know what he valued in life and what his likes, dislikes and thought processes were. So we talked about everything from history, art, sports to politics. We would talk about things that I knew he wouldn’t have any reservations or hesitations to talk about.

People have asked me about the first interrogation I did of Saddam, saying, “What was the topic?” The majority of that first discussion was about his published novel because I knew he wasn’t going to lie about that. And I had researched and studied the book.

Bergen: Was it a good novel?

Piro: No, it was a terrible novel, “Zabiba and the King.”

Bergen: What was the plot?

Piro: So Zabiba was a beautiful Arab woman, and she was married to a horrible old man. Of course, Zabiba represented Iraq. The old man represented the United States. The king, handsome and dashing, rescued Zabiba from her misery, and they lived happily ever after. Of course, you can imagine who the king was. …

A key thing that can enhance the outcome of an interrogation is subject matter expertise. It’s extremely difficult to lie to a subject matter expert. Now, when you add that with a good interrogation strategy and approach, you are really increasing your likelihood of success with an interrogation. As an FBI agent and especially as an interrogator, I knew I wanted to know everything I could about Saddam because inconsistencies are indications of deception.

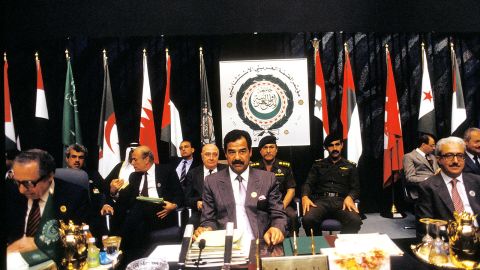

I wanted to understand Saddam and know Saddam as well as he knew himself. To give you an example: Saddam’s decision to invade Kuwait in 1990. I interviewed all the other “high-value detainees,” and we specifically talked about that decision. And there was a critical meeting where Saddam decided to invade Kuwait. I knew where everyone sat in the conference room, what Saddam did, where he even placed his gun belt, and how he positioned it.

So, when I was speaking to him, I would bring up those little details to reinforce how knowledgeable I was and how difficult it would be to misrepresent or lie about facts. It puts a tremendous amount of stress on the detainee when they are facing a subject matter expert because they must think so hard to develop any kind of lie that has a chance of maybe succeeding.

Bergen: At this time, the CIA was running its “coercive interrogation program.” Were you cognizant of this parallel interrogation program, or you found out about it later? And what did you think about it?

Piro: I found out about it later, and of course, I’ve never used “enhanced interrogation techniques,” as they’re referred to. They’re against the US Constitution, against FBI policy, and it goes really against the core values of the FBI. So, for me, it was never really an option because I’ve never used them, don’t know how to use them, nor would I want to. I feel it goes against who we are as a country and what we represent.

What was to my advantage, I was told by the FBI’s assistant director, Counterterrorism Division, “Be prepared to spend a year with Saddam Hussein.” So, I didn’t have to rush through the process. The intelligence value of the information that we wanted from Saddam didn’t diminish over time. It was as valuable whether we got it on Day One or Day 365. It was about getting it. It’s different than when you’re interrogating a terrorist, and there’s a threat or a plot, and you’re under a clock, and your goal is to prevent an attack. So, of course, your approach is going to be different.

What we wanted to know was buried in Saddam’s head, and it was strategic. And it was getting him to share that. So, developing an effective long-term interrogation strategy was really the key.

Bergen: After 9/11, many Americans believed that Saddam was personally involved in 9/11. Did he talk about it?

Piro: As you recall, prior to the invasion of Iraq, there were officials within the Department of Defense that had claimed that Iraq was operationally involved in 9/11, and we had to determine whether that was factual or not. That was our second-highest priority. Our first one was Iraq’s WMD program. Second was the extent of the relationship between al Qaeda and Iraq.

Saddam told me that he didn’t like Osama bin Laden and that he didn’t believe in al Qaeda’s ideology because it aimed to create an Islamic state throughout the Arab world. Well, Saddam had no desire to turn over power or relinquish anything to someone else. Saddam would joke about Osama bin Laden, saying, “You really can’t trust anybody with a beard like that.”

The other Iraqi detainees confirmed that there was no operational relationship with al Qaeda. I would describe it, at best, as an arms-length relationship. Saddam told me it was imperative to find out what al Qaeda was focused on, and then if he could manipulate them, that would be an added benefit.

Bergen: Saddam was a secularist, right?

Piro: Saddam wanted to be considered one of the greatest Arab Muslim leaders in history. In his mind, he was the third greatest warrior in Arab Muslim history.

Bergen: Up there with Saladin?

Piro: Yes. It was the Prophet Mohammed; No. 2, Saladin; and then he’s No. 3. So, for Saddam to be recognized as that kind of great leader and warrior, he had to be seen as religious. But he was very secular. He promoted Arab nationalism versus the Islamist perspective. He was more focused on the Arab aspect of Iraq versus the Islamic aspect of Iraq.

Bergen: Tariq Aziz, his foreign minister, was a Christian, right?

Piro: Yes. Tariq Aziz was his deputy prime minister, at one point, and his minister of foreign affairs. He was Chaldean, which is Catholic, and Saddam never forced him to convert or anything like that. Most of his staff in his palaces and presidential sites were Christian.

Bergen: Weapons of mass destruction: How did that come up, and what did he say?

Piro: When I was selected to interrogate Saddam, I went over to the CIA at Langley (Virginia). I met with officials from the agency, especially those focused on Iraq and Saddam. I was allowed to review previous reports of Saddam’s CIA debriefings, and it was very evident to me that Saddam was very reluctant and unwilling to talk about WMD and al Qaeda, especially initially. He was very guarded.

So, for me, I wasn’t going to bring up WMD or al Qaeda until I felt Saddam could be honest, forthcoming and willing to discuss the topic. It didn’t make any sense to bring up something when you know he won’t want to provide truthful answers or engage in the topic.

We put the WMD and (al Qaeda) questions aside, and the initial focus was developing rapport that was going to be critical as time went on and when it was going to be necessary to bring up those difficult or sensitive topics.

On his 67th birthday, while he was in prison and I was interrogating him, the Iraqi people had the opportunity to show not only the world, but more importantly to him, how they truly felt about him. And they did. And it was overwhelming hatred.

The Iraqis were celebrating not being forced to celebrate Saddam’s birthday, and that day, he saw that on TV. And it took a significant emotional toll on him, and all day, that affected him. It made him depressed, and at the end of the day, the only people who cared that it was his birthday and took time to really recognize it were agents of the FBI.

My mom made some homemade cookies, and I brought them to him. We had tea.

It picked up his spirits, and that was part of the process for consistently looking for different ways to strengthen that rapport because there did come a time when he said, “I don’t want to answer any questions,” but then he goes, “But I still want to talk to you.” And it got to the point where I was able to say to him, “Listen, if you don’t want to tell me something, that’s fine, but don’t lie to me. It’s disrespectful.”

So, when it came to WMD, I didn’t bring it up until about five or so months into the interrogation.

Bergen: And what did he tell you?

Piro: So, what he told me was that, of course, Iraq did not have the WMD that we suspected he had; Saddam had given a critical speech in June of 2000, which was a speech where he said that Iraq had WMD, and a lot of people wanted to know why — if he didn’t have WMD, why did he give that speech? So they wanted me to ask him about the speech, and I looked for a way or an opportunity to bring up the topic and be able to have a candid conversation with him about the speech without him realizing I was interrogating him about WMD.

And when he told me about that speech, his biggest enemy wasn’t the United States or Israel. His biggest enemy was Iran, and he told me he was constantly trying to balance or compete with Iran. Saddam’s biggest fear was that if Iran discovered how weak and vulnerable Iraq had become, nothing would prevent them from invading and taking southern Iraq. So, his goal was to keep Iran at bay.

Bergen: In that period before the US invasion, he was posturing that he had WMD or being ambiguous about it to deter the Iranians from invading Iraq. Is that what you’re saying?

Piro: Absolutely. Because that was his most significant threat. It wasn’t the United States. It was Iran, and he was purposely being misleading or kind of ambiguous about it. If you recall before the war, every intelligence agency around the world had come to the same conclusion that Iraq had WMD because of Saddam’s posturing, some of his vague statements and his prior history of using chemical and biological weapons against his people and also developing a nuclear weapons research program. And that worked to his advantage when it came to Iran.

Bergen: And, of course, during the 1980s Iraq and Iran had fought a nearly 8-year-long war in which hundreds of thousands died on both sides. So that was keeping him up at night, even more than the Americans, right?

Piro: Absolutely. Because if you recall, initially, the Iranians were making significant gains, even though the Iranian military, at least the leadership, was purged. They were able to seize some Iraqi land initially during the first phase of the war, and then there was a stalemate.

And what really turned the tide was, in 1987, where Iraq was able to fire and strike deep into Tehran, but the Iranians couldn’t respond because they didn’t have the weapons capability Iraq had. So they couldn’t bring that same type of response. And that’s what brought Tehran to its knees and forced Ayatollah Khomeini to come to the negotiating table.

Saddam couldn’t afford to let the Iranians realize he had lost that capability because of US sanctions and the weapons inspections of Iraq. He “bluffed” his biggest enemy into believing he was still as powerful and as dangerous as he was during the 1987-’88 time frame.

I asked Saddam, “When sanctions were lifted, what were you going to do?” He said, “We were going to do what we needed to do or what we would have to do to protect us.” Which was his way of saying he would have reconstituted his entire WMD program.

Bergen: Was he surprised by the US invasion?

Piro: No, he wasn’t surprised when it happened. Initially, he didn’t think that we would invade. If you look at the majority of 2002, he was under the impression we were going to do airstrikes, as we had done in 1998, the US bombing campaign called Desert Fox, which was four-day aerial strikes, and he was able to survive that.

So that’s why he was defiant until September 2002, which is when he realized that President Bush intended to invade Iraq. So, he changed his position or posture and allowed weapons inspectors into Iraq to try and prevent it. Still, he told me that probably by October or November 2002, he realized that war was inevitable and then started to prepare himself and his leadership and military for war.

Bergen: Do you think he was surprised by how quickly the US toppled his regime?

Piro: He told me that he asked his military commanders to prepare for two weeks of conventional war, and then at that point, he expected and anticipated the unconventional war or the insurgency would kick in, and that would be a much more challenging type of warfare for the United States.

Bergen: Well, that turned out to be exactly right. … A good part of your interrogation became the basis of the trial of Saddam, right? You delved into his crimes against his people, and that evidence eventually was used in court against him and led to his trial and eventually his execution. Is that correct?

Piro: That’s correct. So, our primary goal was to collect intelligence, to answer the two key questions that brought us to war but also collect any evidence that would be helpful for his eventual prosecution because everyone understood, at some point, Saddam had to face justice for the horrible atrocities that he was responsible for.

So, we focused also on historical events: We talked about the invasion of Kuwait and the gassing of the Kurds. Saddam did make critical admissions, and not only Saddam but so did all of his other subordinate leaders.

So, we were able to gather all of that type of evidence and compile it, and I was fortunate enough to be asked to put together the report that was the basis of Saddam’s prosecution. We located and identified witnesses that survived those attacks that were willing to travel and appear in court in front of Saddam and testify to his crimes and we recovered documents and audio that supported the case.

Bergen: The big question 20 years later is, was it all worth it? You look at Iraq, and there was the civil war in which hundreds of thousands of people were killed. Al Qaeda had no presence in Iraq under Saddam, but after the US invasion, a powerful al Qaeda branch known as al Qaeda in Iraq sprang up, which eventually morphed into ISIS. Then you have the spread of sectarianism, which has always existed in the Middle East but was undoubtedly amplified by the Iraq War and spread into Syria and became part of that civil war.

Saddam was a terrible human being. He’s one of the most murderous men of the late 20th century. Yet, at the same time, he kept a lid on things in Iraq, which had a functional education system and a relatively educated population, and that all blew up due to the US invasion. So how do you reflect on all this?

Piro: That’s a very tough question. Saddam is one of the most brutal dictators of our time and was responsible for some of the most horrific atrocities in history. But on the other hand, he told me we had no idea how difficult it was to rule Iraq, but we would figure that out by removing him.

And then you ask yourself, was it worth it? As an FBI agent, thankfully, I was not in a position to think about that or focus on that; my job was to interrogate.

On the other hand, what frustrates me more is that there were key opportunities at the beginning of the war and significant failures on our part, and if we had not made those, I wonder how different Iraq would look today.

Bergen: And what are those failures?

Piro: For me, one of the biggest was the US dismantling the Iraqi military.

Bergen: Why?

Piro: The biggest employer in Iraq in 2003 was the Iraqi military. So, we come in, and we completely dismantle the military. As in any country, a soldier relies on their salary and benefits to survive, and most have families and obligations, and responsibilities.

We didn’t realize the impact of that decision, and we just fired everyone. We didn’t think about how that was going to affect the situation in-country when you look at a workforce with a unique skill set and training that’s not transferrable to a lot of other things. And as a result, they became disgruntled and angry, and that was initially the basis of the insurgency that we faced in 2003 and 2004.

We had a very short time frame to really leverage the removal of Saddam before the Iraqi people saw us as an occupying force. I believe we had a six-month window, and we made huge mistakes.

Bergen: Now that you’re a private citizen: Do you have a reflection on where Iraq is now and what the future might look like?

Piro: I’m not too optimistic about the future of Iraq, primarily because what Iraq needs is a leader who puts Iraq first. That was the one thing Saddam did — he put Iraq first, in a sense, and consolidated everybody together. As you look at how divided it is, until someone comes in and doesn’t care about your religious or ethnic background and thinks of Iraq as one country, its future will be a challenge.

Bergen: Eventually, Saddam was executed by the Shia-dominated Iraqi government in December 2006. A video was broadcast on state television showing that moments before Saddam was hanged, the guards who brought him into the execution chamber mocked him, shouting the name of a famous Shia cleric. Did you see that? What was your reaction?

Piro: Yes. I did see that, as it was aired on every news channel around the world. And I’ll be honest, I did not enjoy it — and I’ve only seen it once, and the reason why I didn’t enjoy it, is it took away from the legality of it, right? Saddam was executed based on a conviction for the crimes that he had committed against the Iraqi people. Still, when you look at how he was executed: It looked like vengeance.

Bergen: And for people who haven’t seen this tape of Saddam’s execution, what was (it) about this that you thought was wrong?

Piro: He and I talked about his upcoming execution because he knew he was going to be convicted and executed, irrelevant of what kind of defense he raised or anything like that. So, for him, his trial and his execution were to repair or redeem his image. He wanted to overcome the image of being pulled out of the hole where he was captured by American soldiers, looking disheveled, and some labeled him as a coward for not resisting or fighting. So, for him, his trial and execution were what he wanted to utilize to erase that and give something else for people to remember him by.

At his execution, as he was brought in, those who were implementing the execution were mocking him. They mocked him, and he laughed them off, and he prayed. He didn’t have to be helped to the rope, and he didn’t wear a mask to cover his face. He came across as very defiant and, in a sense, very strong or brave. And that’s what people remember, especially among the Sunni population in the Arab world.

Bergen: And now you’re writing a book. How are you putting that together?

Piro: With the Bureau’s approval, I am writing a book about the experience. My goal is to allow the reader to have a seat inside the interrogation and to feel like they’re sitting right there watching it firsthand, not just what Saddam said because some of that is already available, but more about the experience itself, the challenges, the chess game he and I played.

I also got an inside view of the journal he kept and was able to see his thoughts and his perceptions when he was in prison. Saddam told me I got to know him better than his two sons did because I ended up spending more time with him than his two sons did. So, all of that will be in the book to give the reader insight not only into the brutal dictator but also into the other sides of Saddam Hussein.

Bergen: Well, that’s going to be a fascinating read.