CNN

—

Marzena Stasieluk needed a new kidney. She’d been diagnosed with kidney disease in 2015, and ultimately needed dialysis, a grueling process where a machine did the work her kidneys could no longer do.

But in order for a kidney transplant to succeed, she needed a liver first. Stasieluk’s liver disease had been controlled for more than a decade, but it worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic. It wasn’t so bad that she would be prioritized for a liver from a deceased donor, her family said, but bad enough that a kidney transplant likely wouldn’t work.

Marzena’s daughter, Jennifer Stasieluk, is a nurse who has cared for patients in the hardest of times, through Covid-19 and cancer. She was willing, even eager, to give her mother a kidney. They’d done all the scans and test, but it wasn’t going to work.

Although they had the same blood type, her mother is among a subset of patients called “highly sensitized.” Marzena had a high number of antibodies against foreign tissues – a factor that increases the likelihood an organ will be rejected and makes it much harder to find a match.

“She needed a new liver to do a kidney transplant. However, her liver by itself wasn’t sick enough,” recalls Jennifer, 29. “So, they kind of, like, threw their hands up and were just, kind of, like, ‘sorry.’ ”

In January 2020, an appointment with Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, introduced a new idea: Doctors suggested Marzena get a portion of a liver from a living donor.

Jennifer insisted she get tested. Despite her mother’s protests, she wouldn’t take no for an answer. And this time, the response was a good one.

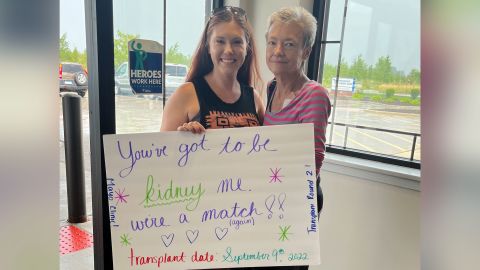

“I kicked her door open in the morning when I got that call that I was a match. I said ‘Mom, I’m a match, pack your bags, surgery’s in six weeks.’ We couldn’t believe I was a match,” Jennifer said.

On June 25, 2021, Jennifer gave her mother a lobe of her liver. Jennifer spent five days recovering in the hospital, and Marzena spent 11. For living donors and recipients, the liver has the unique ability to regenerate in a matter of weeks, and recovery was successful for mother and daughter.

But Marzena, affectionately known as a “professional grandma,” had to continue with dialysis, and was desperate for a normal life.

“It was awful. You sit there three days a week for over three hours,” said Marzena, who lives in Illinois. “My kids and my grandkids are the whole world and that’s why I was fighting for so long. I don’t want them, the kids and my grandkids, to lose me.”

After the liver transplant, Jennifer was prepared to donate a kidney to a stranger as part of a paired donation – a process in which living donor’s kidneys are swapped so recipients like Marzena receive a compatible organ.

Jennifer went through another round of bloodwork and tests to prepare for kidney donation. But then came a surprise: Because of the effect Jennifer’s liver had on her mother’s immune system, she was now able to give her mother a kidney.

“We never in a million years thought that I would be a direct match,” Jennifer said. “I was excited for it. I wasn’t nervous. I knew I was in good hands.

“I gave her the bigger lobe of my liver on June 25, 2021. And then a year later, a kidney.”

Dr. Timucin Taner, division chair of transplant surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, performed the liver transplant for the Stasieluks.

He and his colleagues have been studying the effect of liver transplants on the immune system, including research into how a liver transplant before a heart transplant – not the typical order – can reduce organ rejection.

Taner said the Stasieluks are the first case they’re aware of where a liver’s effect on a patient’s immune response allowed for a subsequent kidney transplant from the same donor. They’re planning to write a case report about the procedures.

“She donated two organs a year apart to the same person,” Taner said of Jennifer. “So she saved her mom’s life twice.”

Taner says organ donors, living or deceased, are heroes. There simply aren’t enough organs to provide for everyone who needs one.

Across the country, nearly 106,000 people are on the national transplant waiting list according to the United Network for Organ Sharing. So far this year, nearly 40,000 transplants have been performed.

“On average, typically about 25,000 people in the U.S. are waiting for a liver transplant on the waiting list,” Taner said. “And of those, every year we can only transplant up to about 9,000 of them because that’s only how many livers we have.

Jennifer described working long, late shifts as a nurse helping patients and their families during the height of the pandemic. There were dark days when answers were few and hope was sometimes hard to come by.

“Losing patients to Covid was devastating. I felt so helpless,” Jennifer said.

But donating organs to her mother – twice – was empowering.

“Just knowing that there is something I can do that is not hopeless … just having that power that I can actually do something and help her and save her life, it was amazing,” Jennifer said.

This will be the first Christmas in about seven years when Marzena is feeling healthy. Jennifer said it’s more special than any holiday before.

Marzena said her daughter’s gifts changed her life.

“Today, I am grateful. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to say enough, thank you,” Marzena said, fighting back tears. “What do you say to a person that donated two organs, not just one?”