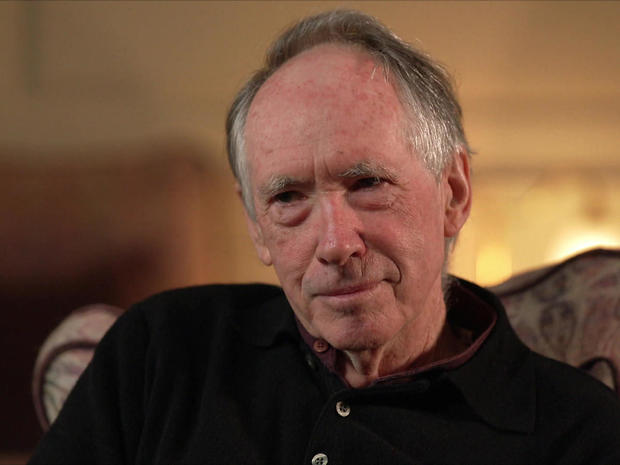

“A secret, I think, can be fatal,” said acclaimed novelist Ian McEwan. “She died with her secret intact.”

That secret McEwan is talking about was a personal one held by his mother: “She would give birth to a baby boy, and she gave that child away. The moment she gave that child away, I think that woman vanished.”

He noted, “These things aren’t resolved.”

This dramatic storyline of a long-lost full brother is from the author’s own life. Now, it’s a subplot in his latest novel, “Lessons.”

“My mother went with her sister with the baby, and gave it away to the strangers who had applied to the ad,” McEwan told correspondent Seth Doane. “And 60 years later, that baby turned up in our lives. That story, I knew I had to write one day.”

CBS News

McEwan has made a career of dreaming up stories. Usually they start as inventions scribbled in a green notebook. “It has to be green,” he said.

Why? “Every rationalist has a soft spot! It has to be black pen, has to be black ink. I’d never write in here in blue.”

He said he’s resisted “plundering his own life for plot-lines,” until now.

McEwan, one of Britain’s most successful living writers, is perhaps best known for “Atonement,” the prized novel which sold more than 7 million copies and was turned into a hit film.

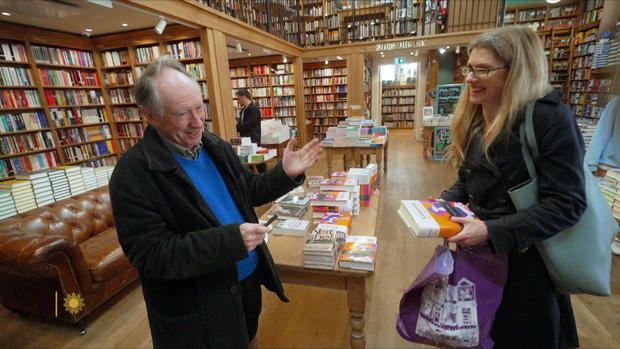

At Topping & Co. Booksellers, in Bath, England, the bestselling author gets the literary world’s version of a rock star greeting. One woman, recipient of McEwan’s autograph, said, “An absolute thrill to happen upon you, thank you!”

CBS News

The store featured a stack of his work, including “Lessons,” a winding lifelong journey chronicling love, child sex abuse, and lost opportunities. It was store manager Kathleen Smith’s “Novel of the Year.” “I found it very, very nourishing, an extremely rewarding read,” she said.

Doane asked McEwan, “How is it to write something that then someone you don’t know reads and is touched by it?”

“It’s a miracle. We take it entirely for granted, that someone can put symbols on a page and transfer their thoughts from their brain to another,” he replied. “Look at these shelves stacked with pieces of other people’s minds, people long dead!”

Doane said, “It’s funny, I keep trying to talk about your book, but you keep getting distracted by other people’s books.”

“Other people’s book are much more interesting to me!” McEwan smiled.

CBS News

That’s not deterred him from writing plenty of his own. “Lessons” is his 18th novel. But when asked by Doane, McEwan appeared to have lost count. “I’ve been at it 52 years,” he explained.

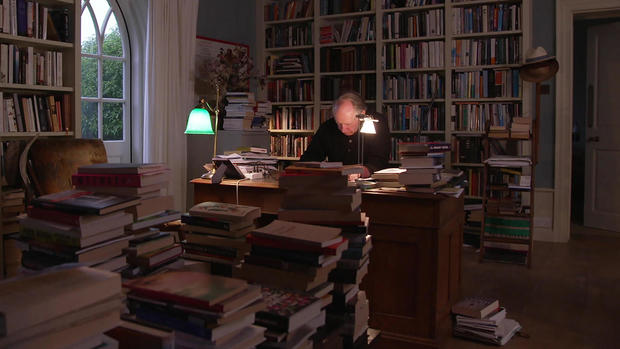

Evidently, it’s been a successful half-century-plus. He lives in the Cotswolds, a couple hours from London.

Doane said, “This is what you’d imagine an English author’s home to be like.”

“I know, I can’t quite believe I live here, actually! We wanted a big, sprawling house where there’d be noisy family Christmases and so on, and it’s actually turned out to be a children’s paradise, as well as one for us.”

It was a paradise where, during the pandemic, this grandfather of eight holed up with his wife and wrote the 500-page “Lessons.” “Sometimes 12, 14, 16 hours a day, seven days a week,” he said.

“You could write 16 hours a day?”

“With lots of breaks for, you know, walking this very energetic dog! But, yeah.”

CBS News

Doane said, “‘Lessons’ is autobiographical in many ways?”

“I’d say about a quarter of it is,” McEwan said. “But its central figure, Roland Baynes, I think he lives the kind of life I might have led had I missed out on a formal education, never got the full passion of reading, which is actually what led me to become a writer. So, he is a kind of alter ego.

“There’s a crucial scene where Roland goes to confront the woman who had sexually groomed him and abused him. I wanted to ring the doorbell with him, and let the scene unfold and find out what happened.”

“You’re turning as the reader wondering what’s going to happen. It’s hard to imagine that you, the author, was doing the same thing.”

“Yeah, absolutely. You write it to find out what’s going to happen.”

McEwan says there’s nothing autobiographical about the sexual abuse. The “vulnerabilty of children” is a theme he’s explored before. His 1978 “The Cement Harden,” which was turned into a movie, explores a sexual relationship between siblings who’ve encased their mother’s dead body in cement in the basement.

“I can never really explain away the darkness of those stories,” he said.

“They cover really dark issues – bestiality, incest, [yet] you seem like such a fine, upstanding gentleman,” Doane said.

“I was a very fine, upstanding, gentleman, even then.”

“So, where did it come from?”

Knopf

“It was the return of the repressed, I think,” McEwan replied. “There must have been some internal unconscious pressure to just throw it all to the winds – that polite, upstanding young man – and shock everybody.”

“What is it about people, audiences that make so many people want to read this grim, dark, scary stuff?”

“I think it’s a way of playing out our worst fears in the luxury of our sitting rooms,” he said. “We want finally to explore the human condition. We know that we’re capable not only of great love and courage and sacrifice and kindness, but of also unbelievable cruelty.”

In all, more than a dozen of his novels and short stories were made into films, including “The Comfort of Strangers,” “Enduring Love” and “On Chesil Beach.” But ultimately, his faith still lies in his original passion.

McEwan said, “I don’t know if you’ve experienced this, going back 20 years to the movie that you really loved at the time and finding how wooden or stilted it is. I don’t find that with books in the same way. That’s why I’m optimistic about the future of the novel.”

Doane asked, “When you have all of this, this beautiful house and this beautiful place, what pushes you to keep working these 14-, 16-hour days, to keep writing?”

“It’s no longer a job; it’s a way of being,” he replied. “And to stop doing it would be to cease existing, I guess. It just soaks into your skin. You can’t live without it.”

READ AN EXCERPT: “Lessons” by Ian McEwan

For more info:

Story produced by Mikaela Bufano. Editor: Brian Robbins.