A smaller subset of this data — known as the Xinjiang Police Files — was published last May. Further examination of the files then revealed their full extent, uncovering approximately 830,000 individuals across 11,477 documents and thousands of photographs.

The police files were hacked and leaked by an anonymous individual, then obtained by Adrian Zenz, a director of China Studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a US-based non-profit. Zenz and his team spent months developing the search tool, which they hope will empower the Uyghur diaspora with concrete information about their relatives, after years of separation and silence.

Using the new online search tool, CNN tracked down the records for 22 individuals after trialing it among the Uyghur diaspora across three continents.

For the first time, exiled Uyghurs were able to see official Chinese documents about the fate of their relatives, including why they were detained — and in some cases how they died. On seeing the files, some described a sense of empowerment; others felt guilt that their worst fears had been confirmed.

The Chinese government has never denied the legitimacy of the files, but state-run news outlet The Global Times recently described Zenz as a “rumor monger,” and called his analysis of the files “disinformation.”

‘Tens of thousands’ detained

The new website represents the largest data set ever made publicly available on Xinjiang. It allows people to search for hundreds of thousands of individuals in the raw files, using their Chinese ID card numbers.

Most of the information is from two locations — Shufu county in Kashgar and Tekes county in Ili — where the researchers believe they have almost complete population data.

The Uyghur population of Xinjiang is around 11 million, along with around four million people from other Turkic ethnic minorities. As such, the data likely represents only the tip of the iceberg.

Zenz said “tens of thousands” of people were listed as “detained” in the documents. The youngest was aged just 15.

“(This is) an inside scoop on the workings of a paranoid police state, and that’s absolutely frightening. The nature of this atrocity is becoming more and more clear.”

Adrian Zenz

CNN has sent a detailed request for comment to the Chinese government about the files, and the families highlighted in this article, but has not received a response.

The leaked police records mostly cover the period between 2016 and 2018, which was the peak of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s “Strike Hard” campaign against terrorism in Xinjiang.

The US government and UN estimated that up to two million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities were detained in a giant network of internment camps, described by the Chinese government as “vocational training centers” designed to combat extremism.

These files provide a snapshot of that timeframe, but do not reflect the current situation.

After the first set of data was published in May, the Chinese government did not respond to specific questions about the files, but the Chinese embassy in Washington DC did issue a statement claiming Xinjiang residents lived a “safe, happy and fulfilling life,” which it said provided a “powerful response to all sorts of lies and disinformation on Xinjiang.”

At a press conference in late December, Xinjiang officials also claimed that “most” of the people identified in the leaked photographs were “living a normal life,” without specifying the fate of the rest. A woman who appeared in the files also claimed that she had “never been detained,” but had graduated from “a vocational college in June 2022,” just weeks after the documents were published.

‘It haunts you every day’

Over the past four years, CNN has gathered testimonies from dozens of overseas Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities, which included allegations of torture and rape inside the camp system. CNN also spoke to those abroad desperately seeking information about their loved ones.

Such information is usually incredibly hard for relatives to find. A sophisticated system of collective punishment threatens those in Xinjiang with detention if their families abroad even try to make a phone call.

“The black hole is the most terrifying thing,” Zenz said. “And that’s part of why the Chinese state creates this black hole. It’s the most terrifying thing that can be done. That you don’t even know the fate of a loved one, are they alive or dead.”

From different corners of the globe, the search tool enabled three Uyghur families to find detailed official data on their relatives for the first time.

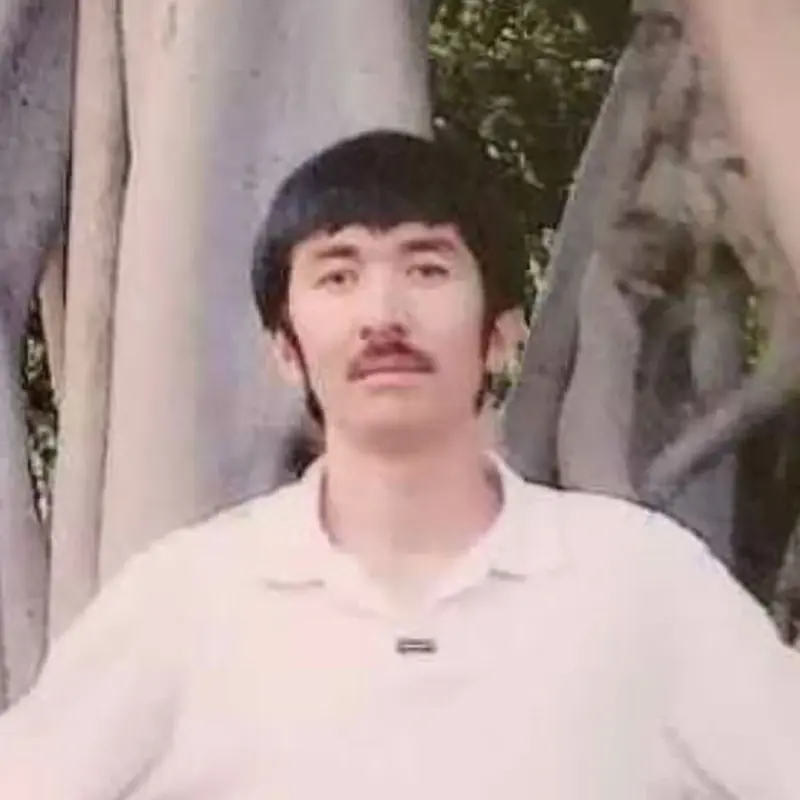

Mamatjan Juma

Lives in Virginia, USA

Age 49

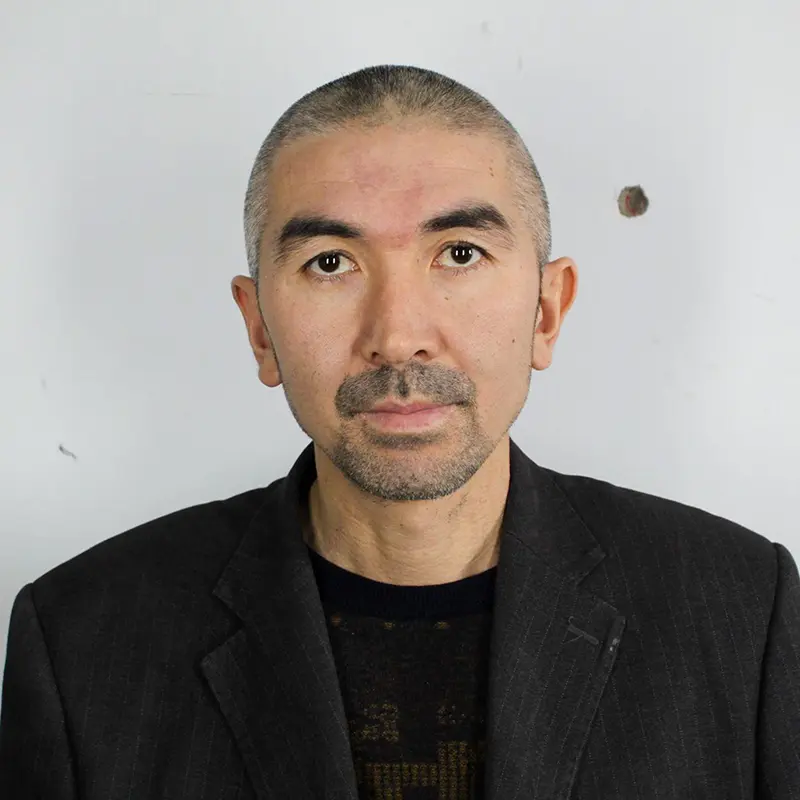

Abduweli Ayup

Lives in Bergen, Norway

Age 49

Marhaba Yakub Salay

Lives in Adelaide, Australia

Age 34

For Mamatjan Juma, who lives just south of Washington DC in Virginia, the files provided “immense” information about his family, but also confirmed his worst fears — that they were found “guilty by association” with him.

As the deputy director for the Uyghur service of US-funded news organization Radio Free Asia, Juma has been highlighting the situation in Xinjiang for 16 years. He left China for the US in 2003, after being selected for an academic fellowship with the Ford Foundation.

“They called me a wanted terrorist, to be deported back to China,” Juma said. “My relatives (are) also demonized because of me, and then (they’re) not described as human beings.”

The files show that 29 members of Juma’s immediate and extended family had been detained — and in some cases sentenced to long jail terms — due to their connections to him.

Juma learned that all three of his brothers were imprisoned, one of whom was even pictured in a police mugshot.

“He looked (like) he lost his soul. It broke my heart. It broke… my heart sank.”

Mamatjan Juma, looking at his brother Eysajan’s mugshot

He described his younger brother, Eysajan Juma, as “jubilant, very gregarious,” a sociable and likable person who was loved deeply, despite making “a lot of mistakes.” But Juma could no longer see those familiar traits in his brother’s eyes.

“I saw a defeated person,” Juma said. “He lost any of his emotions.”

In the files, Juma also discovered the details of his father’s death, which was described as the result of “various kinds of complications.”

“It was a very heartbreaking situation,” Juma said, through tears. “He was so proud of us, (but) we weren’t able to be with him at the time… it was very painful.”

Despite the disturbing revelations, Juma said he felt a sense of “relief” from seeing the files, which was “empowering” after years of not knowing.

“The bitterness of desperation dissipates,” he said. “The darkness of not knowing also disappears.”

But Juma is still coming to terms with the enormity of the impact his departure from his homeland had on his family.

“Survivor’s guilt is very painful,” Juma said. “They are tied to you and they are persecuted; it’s not an easy feeling to digest.”

“It haunts you every day.”

Targeting geography teachers

Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur scholar living in exile in Norway, doesn’t feel any relief from searching through the police files — only grief.

In fact, he wishes he had never seen them.

“Of course if I have this option, I choose to be ignorant, not to know. How can I dare to face this reality?”

Abduweli Ayup, on finding family members’ records

Ayup, who ran a Uyghur language school in Kashgar, fled Xinjiang in August 2015 after spending time in jail as a political prisoner, where he told CNN he faced torture and gang rape.

He had already heard that his brother and sister — along with several others — had been targeted because of him, but the search database gave him the first official confirmation.

“This time the government document told me that yes, it is related to you, and it is your fault,” Ayup said, adding that he now feels “guilty and responsible.”

His sister, who taught geography at a high school for 15 years, was listed in the police files as one of 15,563 “blacklisted” people.

“I have learned that my younger sister, she got arrested,” Ayup said. “The reason is, she (is) accused of (being a) ‘double-faced government official,’ and she (was) blacklisted because of me.”

Uyghurs working in government jobs in Xinjiang while continuing to practice their cultural beliefs were often accused of being “two-faced,” Ayup said, categorized as “traitors, not 100% loyal to the government.”

‘I will live in fear’

When she first used the new search tool, Marhaba Yakub Salay, a Uyghur living in Adelaide, Australia, found police records for two relatives she did not expect: her young niece and nephew, who were aged just 15 and 12 when the files were made in 2017.

The nephew was labeled as a “Category 2” person on the blacklist, described as a “highly suspicious accomplice” in “public security and terrorism cases.”

The files on Salay’s niece and nephew suggested they had traveled to at least one of 26 “suspicious” countries which included Syria and Afghanistan. Salay said that was not true — they had only ever traveled outside China to go on holiday to Malaysia.

“This is insane… this is terrible,” Salay said as she read through her nephew’s file. “He’s turning 18 in a couple of months’ time. Are they going to arrest him?”

Salay’s sister Mayila Yakufu — the mother of the children — was sentenced to 6.5 years in jail at the end of 2020, after she had spent several years in other camps.

Yakufu is accused of financing terrorism after she wired money to Salay and their parents in 2013, so they could buy a house in Australia — which the family has proved with banking records. Mayila and Marhaba’s brother left Xinjiang in 1998, and later died in an accident in Australia in 2007 — but his ID card was still cited as a suspicious connection to the children.

“I think the suspicion level (Category 2) is about my late brother, but they tried to connect my 12-year-(old) nephew with my brother, who passed away 15 years ago,” Salay said. “These two people, they have never met each other.”

“My heart is bleeding. I will live in fear, in the worry about when they’re going to take my niece and nephew.”

Marhaba Yakub Salay, on finding family members’ records

‘Like a virus of the mind’

The extension of “guilt by association” to children reflects the paranoia which the Chinese state holds toward the Uyghur population, according to Zenz.

“The state considers the entire family to be tainted,” Zenz said. “And I think that’s consistent with how Xi Jinping and other officials (in) internal speeches have described Islam like a virus of the mind that infects people.”

As the families look through these files, their instinct is to search for logic and reasons for what happened to their loved ones. But they find only confusion.

“Guilt by association can work quite extensively, and the logic behind it is quite fuzzy and the reach is pervasive,” Zenz said.

This “fuzzy” logic was explained by a former Xinjiang police officer turned whistleblower, who told CNN in 2021 the idea had been to detain Uyghurs en masse first, and find reasons for the arrests later.

The ex-detective — who went by the name Jiang — said that 900,000 Uyghurs were rounded up in one year in Xinjiang, even though “none” of them had committed any crimes. He admitted torturing inmates during interrogations, adding that some of his colleagues acted like “psychopaths” to extract confessions to various crimes.

“Door by door, village by village, township by township, people got arrested. This is the evidence of crimes against humanity, this is the evidence of genocide, because (they) targeted an ethnicity.”

Abduweli Ayup

The US government has accused China of committing genocide in Xinjiang — and a report by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights concluded that China may have carried out crimes against humanity. China has vigorously denied those allegations.

With this new deluge of leaked data, the researchers hope to add to the growing body of evidence on the policies inside Xinjiang — and they hope that providing widespread access to the files will drive renewed efforts by governments and human rights organizations to hold China accountable.

“I sincerely hope that this is going to inspire some hope among the Uyghurs,” Zenz said.

For Uyghur families around the world, desperate to be reunited, each one of the 830,000 names represents a loved one.

“Beautiful souls are being destroyed behind those numbers,” Mamatjan Juma said. “There is suffering without any reason.”

Correction: This story was updated to replace and correct a photo of Abduweli Ayup’s niece.

Have you managed to track down your loved ones using the new search tool? Please contact UyghurFamilies@CNN.com if you’d like to share your stories.