At the request of the defense, the judge on Friday instructed the jury in the Gov. Gretchen Whitmer kidnap trial about what entrapment means — though his instructions on what it doesn’t mean may help the prosecution.

At issue: Did the defendants show any reluctance, the judge noted, or were they already willing participants?

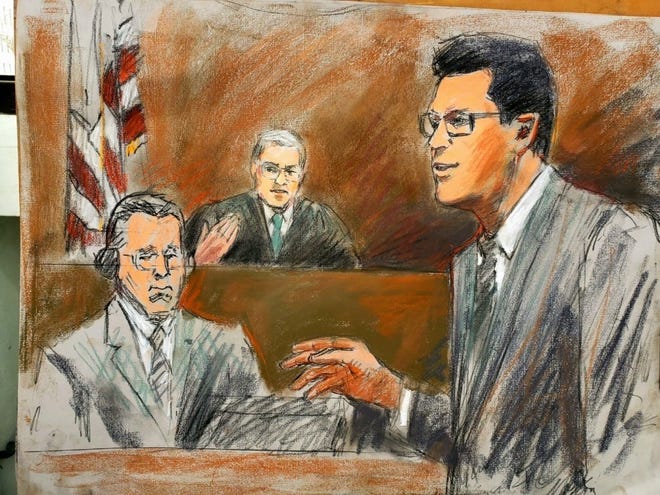

“The crucial question in entrapment cases is whether the government persuaded a defendant who was not already willing to commit the crime to go ahead and commit it,” U.S. District Judge Robert Jonker told jurors, who are set to begin deliberations next week in the retrial of Adam Fox and Barry Croft Jr. on charges they plotted to kidnap Whitmer out of anger over her handling of the pandemic.

More:Defense blasts judge in Whitmer kidnap retrial: You’re favoring the feds in front of jury

More:Judge scolds defense in Whitmer kidnap trial: Stop wasting time talking ‘crap’

Sometimes an agent must ‘pretend to be a criminal’

Fox and Croft have long argued that they were set up by rogue undercover FBI agents and informants who they allege hatched the kidnapping plan and ran the whole show. The prosecution says the defendants were armed, eager and willing to kidnap the governor, never showed reluctance and discussed snatching a governor long before the FBI got involved.

In court Friday, Jonker explained to the jurors the following elements about entrapment:

- It’s not entrapment if someone is already willing to commit the crime.

- Even if the government provides someone with a favorable opportunity to commit the crime, it’s not entrapment if that person is already willing to commit the crime.

- If an FBI agent persuades someone to commit a crime, it’s not entrapment if that person is already willing.

“It is sometimes necessary for a government agent to pretend to be a criminal,” Jonker told the jury, noting there are some key questions to consider about defendants when deciding an entrapment claim:

“Did they show reluctance? And if they did, were they overcome by persuasion? If yes, how much persuasion did the government use?” Jonker said.

To prove entrapment, the defendants must show that the kidnapping idea and momentum for the crime was introduced by the FBI, and that they were not already willing or predisposed to commit the crime — a point Jonker stressed repeatedly.

Jonker named two vital aspects to the entrapment defense — the government had to have taken action to push the defendants to take actions toward the crime, and the defendants had to be at least initially unwilling to commit the crime.

More:Scrutinized FBI informant in Whitmer kidnap plot: I didn’t do it for the money

More:Meet the jurors in the Whitmer kidnap retrial — most don’t like the news

Judge: Don’t be swayed by my actions

Jonker’s jury instructions touched on many themes and controversies that unfolded during the trial — including the defense accusing him of favoring the prosecution.

Jonker repeatedly interrupted the defense lawyers during their cross-examination of government witnesses, cut short their questioning, scolded them for what he viewed as redundant and irrelevant questioning, and, by the end of the trial, imposed a time limit: The defense could only take as long with witnesses as the prosecution did.

At one point during trial, with the jury present, he told a defense lawyer: “Start focusing on what the important issues are, before this trial stretches into Thanksgiving.”

During jury instructions, Jonker urged the panel to decide the case only on the facts — not on anything he did or said.

“Nothing I have done was meant to influence your decision about the facts in any way,” Jonker said, stressing only witness testimony and exhibits approved by the court are to be considered.

“Nothing else is evidence,” Jonker said. “Not the lawyers’ statements or arguments, nor … my legal rulings”

Jonker said that if he sustained an objection, or ruled that the jury couldn’t see something, or struck something from the record, the jury is not to speculate about what that means. Only the witness testimony matters, he said, and the evidence that was allowed in.

“Please don’t interpret my rulings as to suggesting one way or another,” Jonker said. “Don’t let it influence your decision.”

What about the rogue actors?

The jury also heard numerous names during trial, including the names of controversial FBI informants and agents who were kicked off the case in 2020 for various reasons — one was accused of being a double agent — and did not testify at trial. The names of the defendants who were acquitted at the last trial were also mentioned numerous times, though their acquittals were not disclosed.

Jonker instructed the jury to base its decision only on facts involving Fox and Croft.

“Whether someone else should be charged is not for you to consider. It’s only about these defendants,” Jonker said. “Don’t let the possible guilt of others affect your decision.”

Lawyers for Fox and Croft have long argued their clients were merely frustrated with COVID-19 restrictions and talked a tough game, but they would have never gotten as far along in any plot if it weren’t for overzealous FBI informants and undercover agents.

In the first trial, which ended in no convictions, jurors were also given the definition of entrapment. That jury found defendants Daniel Harris and Brandon Caserta not guilty, but couldn’t reach a verdict on Fox or Croft.

Caserta and Harris did not testify in the second trial as they both opted to exercise their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. Their acquittals were never mentioned to the jury.

Doesn’t matter if kidnapping was ‘impossible’ to pull off

Jonker also explained to the jury the crime of conspiracy, which is what Fox and Croft Jr. are charged with as the kidnapping never actually occurred. The FBI arrested five men in a sting in the fall of 2020, alleging fears grew that the group was close to acquiring explosives to blow up a bridge to slow down cops during the kidnapping. Fox and four others were arrested in the sting outside a Ypsilanti warehouse. Croft was arrested at a gas station in New Jersey.

Jonker explained that to prove conspiracy, the government must show the following: two or more people agreed to commit a crime, even if they never achieved their goal. They also must have knowingly and voluntarily joined the plan, and that a conspirator did one or more overt act to advance the plan.

It doesn’t have to be a formal agreement, Jonker said, nor does everyone have to agree to meet the legal standard for conspiracy.

However, Jonker said, people “simply meeting from time to time” is not enough to establish a criminal agreement. This is what the defense argued repeatedly at trial — that the defendants were merely a group of big-talking pot smokers who hung out at a campfire, drank beer, got high and vented about the government.

More:Prosecutor asserts Crumbleys’ ‘toxic’ family life turned their son into a killer

More:Michigan inmate dying of cancer begs Gov. Whitmer for freedom after 46 years

The prosecution counters they did a lot more than vent. They also took action, they said, including: They cased the governor’s house twice, built shoot-houses and practiced breaking and entering into make-believe rooms, drew maps, bought night goggles and communicated in encrypted chats to hide from law enforcement.

Jonker said the government must show “there was a mutual understanding to cooperate with each other to commit the crime of kidnapping. This is essential.”

During trial, Jonker reminded the jury that it didn’t matter if the alleged kidnapping plan was a good plan, or a bad plan. There just had to be a plan, he said.

The defense has argued that any alleged kidnapping plans discussed by the defendants were high-talk by men engaged in fantasy play, such as abandoning Whitmer in a boat on Lake Michigan, or whisking her away in a helicopter.

The judge, however, told the jury on Friday: “You may find them guilty, even if it was impossible for them to successfully complete the crime.”

In closing, Jonker stressed to the jury that it cannot hold it against the defendants that they did not testify, noting they are presumed innocent under the law and that the burden is entirely on the government to prove its case.

He also told the jury that a defendant not testifying cannot be considered or discussed during deliberations, stressing it is not up to the defendant to prove they are innocent.

Second trial much shorter

The first trial, which had four defendants, lasted six weeks and took another five days for the jury to deliberate. This time around, the trial of two defendants lasted just over two weeks as the prosecution trimmed a lot of fat from the case, hoping to salvage the historical domestic terrorism case that highlighted the growth of extremism in America.

Fox, of Potterville, is charged with conspiracy to commit kidnapping and conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction. Croft, a trucker from Delaware, is also charged with the two conspiracies, as well as a third charge for possession of an unregistered destructive device.

The jury will hear closing arguments from both sides and begin deliberations on Monday.

If found guilty, both face up to life in prison.

Contact Tresa Baldas: tbaldas@freepress.com