War is messy, unpredictable.

A battle erupts. Casualties are tallied, battle reports filed. But sometimes, something gets left behind, almost forgotten.

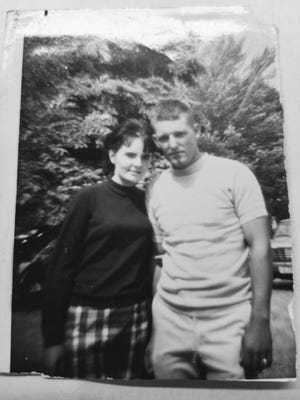

So it was with Donald W. Drake of Newton.

Around 8:45 a.m. on New Year’s Eve 1966, Drake, a U.S. Marine private, was shot to death in a brief firefight with five Viet Cong soldiers near the swollen rice paddies and low hills surrounding the rapidly expanding American military base in Danang, Vietnam.

He was 21 years old and had arrived in Vietnam only a few months before with the 1st Marine Division. A now-declassified battalion report offers only two sentences about the firefight, noting only that a Marine was “KIA” — killed in action — and adding that Marines “searched the area with inconclusive results.”

The Marines brought Drake’s remains back to the hills of northwest New Jersey. After a funeral at a church in Newton, a procession of cars escorted Drake’s coffin to its final resting place in a Presbyterian church cemetery in Sparta where his relatives were first buried in the early 1800s.

Drake’s family — especially his kid brother Brian, who saw Donald as the father he never had — then tried to pick up their lives and move on. But this month, a reminder of Donald Drake turned up: his dog tag.

The sliver of stainless steel — about the size of a potato chip — holds a near-legendary place in American military history and folklore.

To this day, when U.S. soldiers head to the combat zone, they are given two small identical pieces of metal on a single neck chain that look like something the family pet might wear. Each metallic piece carries the soldier’s name, branch of service, blood type, religion and service number.

If the solider is killed, one of the tags is removed for official records. The other remains with the dead soldier’s body to help with identification by burial units.

So why was Donald Drake’s dog tag missing? And why was it still in Vietnam?

The mystery stretches across the globe — and back again — from Vietnam to France and finally to Washington State.

It begins with several French tourists strolling through the stalls of street vendors in Danang. It was 2014, nearly four decades after the last of 58,220 American, 1.1 million North Vietnamese and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers had died in Vietnam. The tourists happened to notice a vendor selling dog tags that appeared to be from American soldiers and Marines. They purchased one as a gift for a friend back in Bordeaux, France.

Weeks later, in Bordeaux, the friend, Rodolphe Urbs, a cartoonist whose work has appeared in such publications as Le Monde, Le Canard Enchaine, and Sud Ouest, studied the silver-colored piece of metal, imprinted with “Drake. D.W.” and “USMC,” along with “A” for blood type, “M” for male, and the religious designation of “Presbyterian.”

Urbs wondered whether the metallic tag was authentic. But how to know?

“My friend told me at the time, ‘Don’t bother. It’s fake. In Vietnam they make fake stuff for tourists,’ ” Urbs recalled when reached in Bordeaux by NorthJersey.com.

Urbs, now 51, was nonetheless perplexed. Whether it was real or fake, wouldn’t Donald Drake’s family want the dog tag returned to them?

But how to find Drake’s family?

Urbs searched for Donald Drake on several websites that listed U.S. casualties from the Vietnam War. One site, titled “The Wall of Faces,” included a “remembrance” page where visitors could leave messages.

On Dec, 29, 2014, Urbs typed: “Hello, I am looking for members of Donal (sic) William Drake’s family.”

Urbs did not say why. He merely listed his email address and signed off as “Rodolphe.”

More than seven years passed.

‘Like a father figure’

Brian Drake, 66, a retired sergeant with the Port of Seattle Police, was only 10 — and the youngest of five brothers and three sisters — when his brother was killed. As he looks back on the moment now, Brian says the news of Donald’s death was devastating.

“Donny was like a father figure to me,” Brian said.

Donald was born April 25, 1945. If he had lived, he would be 77.

Late on Sunday, April 3, 2022, at his home near Spokane, Washington, Brian sat down at his computer.

“I had been thinking of him,” Brian said in an interview. “His birthday was in April.”

On the “Wall of Faces” website, Brian noticed Urbs’ message from 2014. Even though Brian had perused the website before, he didn’t remember seeing the message.

“Hi,” Brian wrote in an email to Urbs. “I just saw this today. You posted a note on my brother’s memorial page.” He added: “I am his brother. Please contact me if you have any questions.”

It was 11:10 p.m.

Seventeen minute later, Urbs responded.

“Oh, hello, Brian,” Urbs wrote. “Well, it was a long time ago but I am very happy to hear from you. Excuse my English. I am French and I will try to be as clear as possible.”

Urbs went on to explain that a friend had found Donald’s dog tag in a shop in Danang. “Call it luck or anything,” Urbs said, adding that “obviously, if you want it, I would be very happy to give it back.”

He added that he did not want any money.

“Let’s be gentlemen,” Urbs wrote. “I supposed it should be in his family hands more than in the southwest of France.”

Urbs signed off, leaving his telephone number and a simple request: “Tell me.”

Brian first asked for a photograph of the dog tag to determine if it was real. When he saw the photo, Brian figured he had to find a way to retrieve the dog tag.

“I may fly to Bordeaux,” Brian wrote in an email. “I have never been to France — I hear that it is beautiful in the spring!”

Eventually, Urbs and Brian opted to contact the United States Consulate office in Bordeaux. The U.S. consul, Alexander Lipscomb, a career foreign service officer, quickly responded.

“I’ve never had this type of request before,” Lipscomb told NorthJersey.com. “In Bordeaux we occasionally receive information on U.S. service members who served in World War I or World War II, but anything pertaining to the Vietnam War is rare.”

More Kelly:America is losing its soul to guns, but our politicians don’t seem to care

More Kelly:Mass shootings are tearing America apart. So why can’t we stop them?

More Kelly:Just before Mother’s Day, COVID claimed a victim close to home — my mother

Lipscomb contacted Urbs. The next day, Urbs brought the dog tag to the U.S. Consulate. Soon after, Lipscomb mailed the dog tag to Brian Drake in Spokane along with a handwritten note saying he was grateful to “play a small role in finally returning Donald’s dog tag to his family after all these years.”

Brian’s wife, Cathy Johnston, a retired manager of the pastoral care staff at a Roman Catholic hospital, remembers her husband’s reaction as he opened the envelope from France and held the dog tag for the first time.

“It was like reaching back through time,” Johnston said. “It’s a tangible connection to his brother, a tangible manifestation. Brian even said, ‘I think there’s still a little bit of dirt around the edges.’ ”

Sovereign relics

So, how did Donald Drake’s dog tag get lost in the first place?

In the U.S. military, dog tags are viewed as sovereign relics — not to be tampered with or lost. But with 2.7 million U.S. military personnel rotating through Vietnam during the nearly two-decade conflict, it’s understandable that some dog tags were lost or misplaced.

What bothers many veterans, however, is how Vietnamese vendors continue to sell dog tags to tourists.

Ray Milligan, now 74 and retired as the police chief of Deptford, served in Vietnam as a Marine in 1967. In 1993, as a logistics volunteer with a group of doctors who traveled to Vietnam to perform surgeries, he noticed street vendors in Danang selling U.S. dog tags.

“I was pissed off,” Milligan said. “There were hundreds of dog tags. I wondered if they were real.”

Milligan bought more than $100 worth. Back in New Jersey, he handed them off to Susan Quinn-Morris, a volunteer at an American Legion chapter in Cherry Hill.

So began a quest by Quinn-Morris to return dog tags — hardly an easy task.

For starters, the U.S. military has taken a hands-off posture on missing dog tags, declining to help return them, monitor their sale by vendors or even determine whether they are real. The Pentagon did not respond to several requests for comment.

Quinn-Morris began the arduous task of trying to track names of U.S. soldiers from the Vietnam era with current relatives.

So far, she’s returned about 200 dog tags.

“I get all different responses from families now,” Quinn-Morris said. “Some are really happy right away. About 75% of the people are skeptical. They think it’s a scam. They think I want money. But I don’t want money. I just want to get it back to them.”

In some cases, she’s been able to track down how a dog tag was lost. Quinn-Morris learned that soldiers sometimes lost their dog tags while relaxing at a beach between trips to a battlefield. In other cases, she said, some soldiers tossed away their dog tags because they were too uncomfortable to wear in the steamy jungles of Vietnam.

But there is no clear answer why so many dog tags were lost.

At home in Spokane, Brian Drake says he does not need an answer. What’s important is that he has his brother’s dog tag. It doesn’t take away the pain of his brother’s death. But it offers a connection to his brother that Brian thought he had lost.

Brian can still recall the emptiness of that day when a Marine officer and a local minister knocked on the door of his family’s home in Newton with the news of Donald’s death.

It was afternoon, a few days after New Year’s. Brian had just returned from ice skating on a nearby pond. His mother cried, and Brian tried to comfort her.

“I answered the door,” Brian said. “I remember it like it was yesterday.”

His brother’s dog tag did not erase that tragic memory. But it eased some of the pain.

Mike Kelly is an award-winning columnist for NorthJersey.com, the author of three critically acclaimed non-fiction books and a podcast and documentary film producer. To get unlimited access to his insightful thoughts on how we live life in New Jersey, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: kellym@northjersey.com

Twitter: @mikekellycolumn