New York

CNN Business

—

Way in the back of the grocery store, at the end of the sleepy baking aisle, sits a brand decades past its prime: Jell-O gelatin.

Today, Jell-O is served to patients at hospitals. Or schoolchildren throw it around during food fights at lunch and college kids swallow it down with alcohol shots. Others associate Jell-O with the disgraced comedian Bill Cosby, who was the face of the brand for 30 years. Jell-O molds and now-defunct flavors like Italian salad and mixed vegetables are in recipe books for “nauseating” foods.

“Jell-O is kind of associated nowadays in our culture with illness and frailty and vulnerability. So it certainly doesn’t have the fun associations that it did when I was growing up,” said Rachel Herz, a neuroscientist and the author of “Why You Eat What You Eat.”

But Jell-O once gave middle-class consumers access to a luxurious food that had only been accessible to the wealthy. Then Jell-O turned into a salad, a staple dish of the mid-twentieth century, and morphed into a fun snack for kids. It was adaptable and versatile. Jell-O became a figure of speech and the state food of Utah, where the state’s large Mormon population is known for its devotion to the product. Jell-O even went to space.

It was this country’s national dessert, eaten by presidents at the White House, depicted in advertising by leading actors and artists, and a symbol of Americana.

Jell-O “displays so many elements of the American character,” wrote Carolyn Wyman in her 2001 book “Jell-O: A Biography.” Jell-O is the “food that most resembles a toy.”

But how did a brand once marketed as “America’s Most Famous Dessert” become an afterthought today?

The genius of Jell-O was to transform an elegant, complex dessert and make it cheap and easy to make.

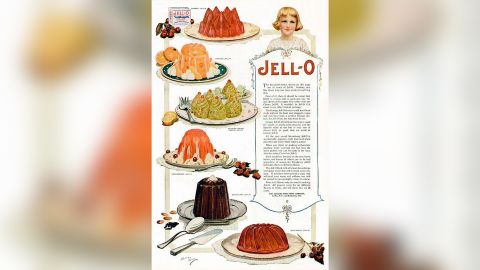

Desserts with gelatin, which is essentially purified glue, have a luxurious history. During the Victorian era in Europe, decorative gelatin molds were a symbol of high society and served to royalty. Gelatin desserts were for the elite who had cooks and servants to labor through the elaborate and time-consuming process of making gelatin, often extracted from the feet of calves or other animal parts.

“If ever there was a food calling out for a convenience product solution, it was gelatin,” Wyman wrote.

In 1897, Pearle Wait, a carpenter in LeRoy, a small town outside of Rochester, New York, found an answer to the problem. Wait, who dabbled with developing cough remedies and teas, added flavoring and coloring to granulated gelatin, a flavorless food ingredient.

Wait came up with a sweet, flavored powder that could be added to boiled water, cooled, and was ready to serve. The first flavors of his product, which were extracted from natural fruits, were orange, lemon, strawberry and raspberry. (It’s not known exactly how he added the colors.)

Wait trademarked a name for his invention, Jell-O, based on an idea from his wife May. How she landed on the name has been lost to history, but some historians believe it was inspired by the product Grain-O, a substitute for coffee, that was also made in LeRoy by the Genesee Pure Food Company.

Wait couldn’t get his new product off the ground. In 1899, he sold the rights to Jell-O to Genesee for $450.

Jell-O’s fortunes quickly changed under Genesee. Orator Woodward, the owner of the company, turned over the advertising, which was in its nascent stages, to ad firms in New York.

The advertising, targeted at women in magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal, stressed how easy the new product was to make — and for only 10 cents, about the cost of a loaf of bread.

Genesee tried to turn Jell-O into a brand consumers would ask for by name, and salesmen would go door-to-door to local grocers to persuade them to place ads of Jell-O in windows and behind the counters. The ads, depicting fancy Jell-O molds in startling new colors, stood out. Jell-O also distributed free recipe books, a new marketing strategy at the time.

By 1907, Jell-O sales crossed $1 million.

Early Jell-O advertising depicted women as inept, needing the help of a simple recipe like Jell-O.

“How often some ingredient is forgotten or not rightly proportioned and the dessert spoiled,” ran another ad. “I couldn’t keep a house without Jell-O.”

Early ads emphasized the beauty and glamor of these desserts that were formerly unattainable to the average household, said Wendy Woloson, a historian at Rutgers University-Camden who studies consumer culture in 19th-century America. “Even you can serve this dessert to your family, without the use of a servant.”

Jell-O “was able to democratize access to a dessert that had formerly been a high end luxury type of dessert only available to the rich,” Woloson added. “That was really significant.”

In 1904, Jell-O introduced the Jell-O Girl, which helped reinforce the idea that children loved Jell-O and that it was so simple to make a child could do it.

The Jell-O Girl was the face of the brand for almost 40 years. Rose O’Neill, a famous artist who created the Kewpie doll, created “Jell-O and The Kewpies” ads for the brand featuring the dolls and the Jell-O Girl.

By 1925, Geneese sold Jell-O to the Postum Cereal Company (which would eventually become the giant General Foods and is Kraft Heinz today) for $67 million.

Jell-O shifted during its next phase.

During the Great Depression and World War II era, Jell-O was pitched as an affordable food, a way to turn a few ingredients into a family meal people could use to stretch their dollars.

Again, Jell-O leaned on new advertising to stand out.

It was one of the first companies to advertise on radio, sponsoring popular comedian Jack Benny’s radio program in 1934. Benny popularized the jingle “J-E-L-L-O” to millions of listeners and it was one of the most successful partnerships in radio advertising history. “Jell-O again! This is Jack Benny talking.”

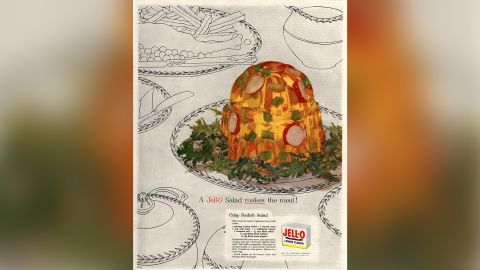

Although Jell-O initially was marketed primarily as a sweet dessert, it took on a new life as a savory salad, driven in part by the introduction of lime Jell-O in 1930.

“Jell-O Salads, Welcome! say the women of America!” read an early ad displaying Jell-O as a salad.

“Shimmering…luscious…Jell-O salads are making this a salad nation!” said another ad in The Farmer’s Wife magazine.

Jell-O congealed salads, often made with fruits, vegetables, Cool whip or other foods, were used to show off at dinner parties and a form of creative expression.

Jell-O released flavors such as seasoned tomato, celery, mixed vegetable and Italian salad, and Jell-O salads were a colorful way to use leftovers in side dishes. In 1955, the company introduced the slogan “A Jell-O salad makes the meal.”

“The Jell-O salad really hits the American sensibility and palate perfectly. Americans have a longtime sweet tooth,” said Laura Shapiro, a culinary historian and author of “Perfection Salad” about women and cooking at the turn of the twentieth century.

“This is the most American thing of all. Nobody but us thinks that a salad is a red molded strawberry flavored thing on a lettuce leaf. But that was one of the big attractions of Jell-O – you could eat a dessert and call it a salad.”

Jell-O was marketed as a light, satisfying ending to a meal even if people were stuffed – typified by its successful 1960s campaign slogan “There’s always room for Jell-O.”

But as more Americans traveled and global cuisines entered the mainstream, the simplicity of Jell-O salads became a downside. Julia Child brought French cooking to American kitchens, and Jell-O seemed bland.

“Upscale becomes the new mainstream and Jell-O salads moves into a niche,” Shapiro said. “Jell-O salads started to look unsophisticated and kind of an antique. They started to look a little silly.”

Jell-O sales peaked in 1968 and then begin a decline of about 2% of a year for two decades, according to Jell-O biographer Wyman. By 1987, the company sold about half as many boxes as it did two decades prior.

With Jell-O salads becoming less popular, the brand looked for its next hit.

But it had a problem: With the increase in women entering the workforce, families weren’t sitting down for as many meals and eating dessert like they once did. And new, ready-to-eat foods were hitting the market that were more convenient.

What was once considered a quick and easy dessert now took too long to make for consumers, especially moms, Jell-O’s longtime target customer.

“It was starting to be looked at as a chore in the mid 1980s,” said Chris Becker, who led the Jell-O account at Young & Rubicam, Jell-O’s longtime advertising agency. “It was perceived as old-fashioned and was creating dust in the cupboard.”

Jell-O began to pivot into new products such as single-serve cups, ready-to-eat Pudding Pops and frozen Gelatin Pops. It transitioned from targeting moms to marketing the product as a snack for kids and one time-starved parents could bond with their kids over making together.

In 1990, Jell-O launched a new product that would transform the brand: Jigglers. It was based on a recipe that used four times the usual amount of Jell-O and could be cut into squares. Jell-O launched a marketing blitz, with supermarket displays, Jiggler giveaways and ads with Bill Cosby.

Cosby had been working with Jell-O since the 1970s as the face of Jell-O’s pudding lineup, but Jigglers was the first gelatin commercials he appeared in. An ad showed Cosby and kids at a formal dinner tossing their spoons to eat the new Jigglers “with our bare hands.”

Cosby “brought that advertising to a different level,” Chris Becker said. “He became the brand.”

While no longer the powerhouse it once was, Jell-O continued to innovate to meet changing consumer tastes.

Kraft in the early 2000’s shifted the focus of Jell-O’s advertising away from kids and toward adults. It pitched sugar-free Jell-O, for example, as a treat for Atkins dieters. But as the Atkins diet slipped in popularity, it took Jell-O down with it.

Jell-O sales fell 19% from 2009 to 2013 to $753 million, the Associated Press reported at the time. Jell-O’s sales have stagnated since. In 2022, they were $688 million, according to IRI.

Jell-O has slumped in recent years because of competition and a lack of investment in the brand.

Kraft tried to restart its Jell-O business when it split into two companies in 2012, said Erin Lash, an analyst at Morningstar.

“It never seemed to get off the ground in terms of resonating with consumers and getting over the overhang of being an unhealthy snack,” she said.

But perhaps Jell-O’s decline had less to do with the perception that it’s unhealthy than changes in consumers’ lifestyles. New salty and sweet convenience snacks with exciting tastes have emerged. Big brands, including Jell-O, have faced competition from a proliferation of startups and direct-to-consumer brands.

“Over the course of the last 10 years, you’ve had a period where social media and online commerce has made it easier for smaller, niche startups,” Lash said. “Consumers have been more willing to purchase brands that they were unfamiliar with.”

Jell-O has also become a smaller focus at Kraft Heinz, its parent, she said, and is a tiny piece of its business. Kraft Heinz’s “easy indulgent desserts” business, which includes Jell-O, makes up just 4% of the company’s total sales.

Jell-O has little presence on Instagram, TikTok and social platforms that are crucial to reaching younger shoppers. It also doesn’t advertise on television to try to reconnect Baby Boomers with the brand.

But Kraft Heinz said big changes are coming to Jell-O next year.

“Jell-O is a beloved family brand with an incredible amount of opportunity,” Emily Kerschner, the vice president of marketing and strategy at Kraft Heinz, said in an email.

Next year, Jell-O will “undergo its first brand renovation” in a decade and increase its advertisement spending, she said. It’s also exploring adjusting the recipe to reduce sugar.

Jell-O still remains a cultural curiosity, said Lynne Belluscio, the former director of the LeRoy Historical Society and the curator of the Jell-O Museum in the brand’s birthplace.

“We have people come through and they say, you know, I really like Jell-O. I’m going to go home and have some.”