“I saw my mother raise a man from the dead.”

Born enslaved, the man’s only way out of the American South was to be sealed into a coffin. He’d arrived in Philadelphia on the business end of a funeral wagon, driven by a woman dressed in richly embroidered mourning clothes.

He survived the trip, but the implications were clear: Sometimes you must die to be free.

This is the taut, extraordinary scene that begins Kaitlyn Greenidge’s 2021 novel, “Libertie,” released this month in paperback.

What’s perhaps more extraordinary is that the story is rooted in truth.

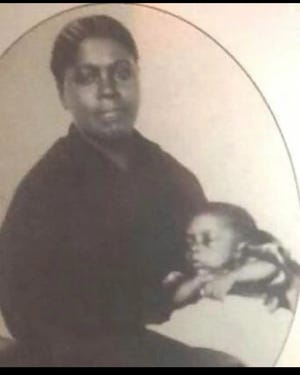

In 1858, Henrietta Bowers Duterte shrugged off the customs of her time to become the first modern female undertaker in America. She lived to become one of Philadelphia’s most prosperous Black entrepreneurs, serving clients both Black and white. By her death at age 86, she owned multiple properties and took in $8,000 a year — well north of $200,000 today.

But Duterte was also an important figure in the Underground Railroad, according to historian Charles L. Blockson, working closely with abolitionists Harriet Tubman, William Still and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.

More:Did you know South Jersey had dozens of stops on the Underground Railroad?

She also used her funeral home as a cover for daring escapes, as documented in his book “African Americans in Pennsylvania.”

“Henrietta Bowers Duterte, the first African-American undertaker in Pennsylvania, on several occasions cleverly concealed runaway slaves in caskets,” Blockson wrote. “She also led slaves dressed in northern clothes from Philadelphia to freedom.”

Her story has remained obscure, often told by historians as a curious footnote. But when Greenidge encountered Duterte’s story in 2017, she couldn’t let go of it. Before Duterte inspired her novel’s haunting first scene, Greenidge wrote about Duterte in a meticulously researched article for now-defunct publication Damn Joan, which included a short animated film.

“It is not so strange to use whatever means you have at hand — a postal box; a fake mustache, top hat, and cane; a coffin and a funeral procession — to ensure freedom for those around you,” Greenidge wrote.

“How I wish I’d known about Duterte as a teenager. She would surely have become my lifelong heroine.”

Philadelphia as crossroads of freedom from slavery

A century after the Liberty Bell arrived by ship, the Philadelphia of Duterte’s day had again become a crossroads for freedom — this time for African Americans who’d been enslaved in the South.

“The objective was to get to Philadelphia,” said Underground Railroad historian William Switala. “Philadelphia had an extremely well-organized Underground Railroad escape network. The Anti-Slavery Society was located there. They had a clearinghouse and well-worked network. A lot of Quakers were involved in this effort.”

Philadelphia was also home to the largest population of free Black people in the North. In the city’s thriving Seventh Ward, later lionized by W.E.B. Dubois, Duterte was born in 1817 to the prosperous Bowers family of clothiers, as one of 13 children.

The Bowers family was marked by both achievement and activism. Henrietta’s brother Thomas became a world-renowned classical tenor known to many as the “Colored Mario” or “American Mario,” after a popular Italian singer — a nickname he reportedly detested. He saw his classical training as an antidote to the entrenched image of minstrel singers, and refused to play in segregated theaters. He was even later memorialized in an episode of TV show “Bonzana.”

Their sister, Sarah, was likewise an accomplished singer, while another brother, John, was a fiery and sought-after public speaker who helped found Pennsylvania’s Anti-Slavery Society.

Henrietta began her career in the family business, as a tailor known for her fashionable cloaks and hats. In 1852, she married Francis Duterte, a cabinetmaker who used his joining skills to make coffins “without the use of nails” to break into a funeral trade that was then still a somewhat novel profession in America.

He was also a strong voice against slavery, and a delegate to the 1855 National Colored Convention.

“We claim that we are persons, not things,” read an 1855 open letter he signed. “And we claim that our brethren held in slavery are also persons, not things, and that they are so held in slavery in violation of the Constitution.”

Francis Duterte was an immigrant from Haiti, where memories of a bloody but failed slave revolution were still strong.

“If you start to sort of look at those Black communities at that time you’ll find French surnames from their original birthplace, Haiti,” Greenidge said, “Those people came to the U.S., and many of them directly influenced organizing around abolition in the U.S.”

But after a sudden illness took his life in 1858. Henrietta was left alone to continue both the abolitionist cause and the funeral business, making history in the process.

“So far as we find record she was the first woman of any race to engage operatively in undertaking and embalming in this country,” wrote “Who’s Who in Philadelphia” author Charles Frederick in 1912, praising Duterte’s “high standard of business efficiency and professional integrity.” She was also the only female undertaker listed in McElroy’s Philadelphia City Directory in 1860.

Duterte’s historical claim as first female undertaker is best understood in the modern sense, as the operator of a funeral home. For centuries, women had been in involved in “laying out the dead” for home burials, including Continental spy Lydia Darragh in the 1700s.

But as the funeral home industry became established in the 1800s with the advent of widespread embalming, it was a male profession. In Duterte’s day, the funeral trade was considered an unheard-of and maybe even unseemly vocation for women.

But in defying the gender norms of her time, she rose to become a broadly respected figure in Philadelphia, praised in African American newspaper The Christian Recorder as “prompt in her business affairs, and sympathizing and accommodating to all — rich or poor.”

She used profits from her successful business to support the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas — the first Black Episcopal church in America — and sat on the board of the Philadelphia Home for Aged and Infirm Colored Persons as a benefactor.

Dangerous, ingenious paths to freedom from slavery

Meanwhile, in strict secrecy, Henrietta Bowers Duterte helped enslaved people find freedom.

She did so at personal peril.

Though Philadelphia may have served as a beacon for liberty, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 exacted severe penalties for helping enslaved people escape even in northern states. So-called “slave catchers” patrolled routes to the city, hoping for a lucrative paycheck.

“The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was very draconian,” historian Switala said. “For each slave that you helped escape, you could get six months in a federal penitentiary. So if you helped two, you got a year. There are some people that languished in the penitentiaries until after the Civil War, when they were set free by Union soldiers. So you took great hazard.”

The law was inconsistently enforced. But steep fines of $1,000 — tens of thousands in today’s money — reduced some to financial ruin, Switala said.

But Underground Railroad conductors such as Duterte quickly learned that white people had a difficult time recognizing people of African descent even after a change of clothing, which may have made the Bowers family’s clothing trade a quite useful profession. Even something as simple as joining a funeral profession in mourning clothes might be disguise enough to reach a safehouse en route to Canada.

“I’ve seen stories where the so-called master walked right by a fugitive slave, and does not recognize them because the guy was clothed differently,” Switala said. “Sometimes they were cross-dressed. Men were dressed as women, women were dressed as men.”

Some reached Philadelphia by boat. Famously, Henry “Box” Brown mailed himself to the Anti-Slavery Society in a cramped four-by-three-by-two box. The box was marked “this end up” — and of course, Switala noted, it was shipped upside down.

Funerals, said Switala, were a far less common route but far from unheard of.

“Someone would pretend to die, he said. “And they would put them in a coffin, and they would take them off the plantation to bury them, because usually there were slave cemeteries in the area. … They didn’t really perform any kind of checking on someone claiming to be dead. I guess it was a fear of contamination.”

Duterte was part of a network of Underground Railroad agents in Philadelphia, and the numbers of formerly enslaved people crossing to Canada reached the hundreds of thousands. How many enslaved people escaped with Duterte’s help, whether in coffins or funeral processions or clothed in northern garb, remains unrecorded.

“Even if it happened just once,” Greenidge said. “it’s still really fascinating.”

After the Civil War, Duterte continued her business and her activism, organizing a Freedman’s Fair to help formerly enslaved people in Tennessee. As a pioneering Black businesswoman, she traveled across the country to speak on behalf of women’s rights.

The funeral business she founded with her husband survived well past her death to 1935, becoming one of the oldest Black-owned businesses in the nation. And though she slowly transferred much of the business to her nephew, she was listed as an undertaker two days before her death on Dec. 23, 1903.

She was buried in Delaware County’s Eden Cemetery, whose grounds also welcomed the father of the Underground Railroad, William Still.

When Mercy Hospital opened in Philadelphia on Lincoln’s birthday in 1907, it was hailed by Chicago newspaper Broad Axe as a “magnificent institution,” perhaps the most impressive hospital in America managed by and for African Americans.

The hospital’s sole private room for women was dedicated to her memory, the newspaper reported: “Henrietta S. Duterte, who was the first woman undertaker in the United States.”

Matthew Korfhage is a reporter for the USA TODAY Network’s Atlantic Region How We Live team. Email: mkorfhage@gannettnj.com | Twitter: @matthewkorfhage