NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

The political landscape is littered with those who underestimated the late Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nevada.

People forget that Reid was a boxer, a U.S. Capitol Police officer and headed the Nevada Gaming Commission – all before joining the Senate in 1987.

Some observations on Reid:

He defeated tea party darling Sharron Angle by six points in the Republican landslide year of 2010. That was an election where Republicans were positive they would not only whip Reid but capture the Senate. In 1998, Reid defeated then-Rep. John Ensign, R-Nevada, by a mere 401 votes.

Reid’s wisp-thin voice betrayed his steely exterior. For instance, barely anyone could hear Reid speak over the din in the Capitol Rotunda during a presentation of the Congressional Gold Medal to golf icon Jack Nicklaus. But that soft-spoken tone didn’t mean that Reid won’t rumble with practically anyone.

FILE 2020: Former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid talks to members of the media outside the East Las Vegas Library after voting on the first day of early voting for the upcoming Nevada Democratic presidential caucus. (Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

(Ethan Miller/Getty Images)

In a 2008 session with the press, Reid scolded journalists for not grasping the nuances of a parliamentary tactic on energy legislation. Reid admonished the scribes that they should “watch the floor more often. You might learn something.”

Minutes later, another reporter still wasn’t clear on Reid’s procedural plan. The Nevada Democrat asked the reporter if she “spoke English” and questioned whether she was hard of hearing.

FILE 2016: Then-Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nevada, hugs incoming Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer, D-N.Y. (Photo By Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

(Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call)

“Turn up your Miracle-Ear,” Reid berated the reporter.

Even visitors to the U.S. Capitol weren’t immune to Reid’s umbrage.

“In the summertime, because of the high humidity and how hot it gets here, you could literally smell the tourists coming into the Capitol,” Reid said during the 2008 dedication of the U.S. Capitol Visitor’s Center.

A master agitator, Reid got under the skin of then-Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, R-Tenn., R-Tenn., in November 2004. Reid seized the Senate floor and engineered a closed session to debate controversial intelligence which led to the war in Iraq. As is Senate tradition, Frist, then the Majority Leader, controlled the floor. But Reid hijacked all of that.

Frist was practically stammering when he stormed out of the chamber to protest Reid’s brazen antic to the press corps.

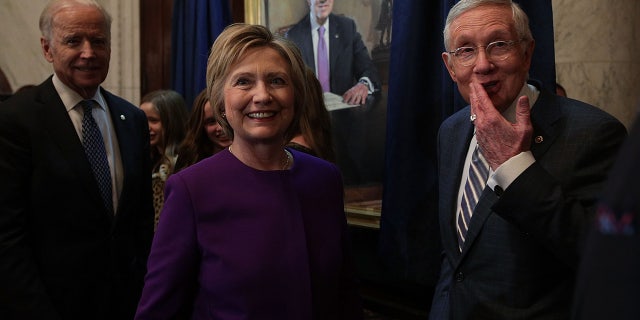

FILE 2016: Sen. Harry Reid, former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and then-Vice President Joseph Biden during Reid’s leadership portrait unveiling ceremony on Capitol Hill. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

“I have never been slapped in the face with such an affront,” steamed Frist. “It’s an affront to me personally.”

Trust between the Senate majority and minority leaders is sacred. Otherwise, the Senate accomplishes little. So I asked Frist what this meant to his relationship with Reid, still new on the job as minority leader.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“For the next year-and-a-half, I can’t trust Senator Reid,” seethed Frist.

Only twice as a journalist have I thought someone was about to deck me after I asked a tough question. The first time was in 2001 when I posed a pointed, post-game interrogatory to hockey great Mario Lemieux after a frustrating playoff loss to the Washington Capitals. The exchange wound up on “SportsCenter.” The second occasion came when I asked Reid at the Ohio Clock that day why he didn’t first “consult” with Frist before executing his parliamentary caper.

“Consult with the Leader so he stops me from going and moving on this? What do you mean consult with him? What are you talking about?” chafed Reid.

I tried to follow up, suggesting such conversation was the Senate norm. Reid cut me off.

“Consult with him? All he would have done is a quorum call and we couldn’t have done this. You’ve got to understand a little bit about the procedures here,” Reid bristled.

TRIBUTES POUR IN AFTER REID’S DEATH

As long as Frist ran the Senate, Reid regularly tangled with the Tennessee Republican over rules. In December, 2005, Reid boiled when Frist tried some parliamentary maneuvers to approve drilling in the Arctic.

“The Republicans in Congress and the White House don’t care about rules and simply will break them when it suits their interest,” charged Reid. “The abusive practice will allow a rule change at any time and change the very nature of the Senate.”

Yet it was Reid who singlehandedly orchestrated one of the most-prominent changes in Senate procedure in decades. In November, 2013, Reid grew increasingly frustrated with Republican filibusters of President Obama’s executive nominees. So after much consternation, Reid altered Senate precedent to limit some filibusters. Under most circumstances, the Senate can overcome a filibuster with 60 votes. But unveiled the “nuclear option,” It short-circuited the rights of the minority by dropping the threshold to end filibusters for many nominations to just a simple majority. That new precedent will echo through the Senate corridors for years.

Reid’s responsibility for the nuclear option is not without irony.

As a freshman senator in December, 1987, the Nevada Democrat found himself before the Senate Rules Committee. The subject? Potential rules changes to halt some prerogatives of unlimited debate – a Senate fundamental which distinguishes the body from the House.

“We are not trying to turn the Senate into another House of Representatives,” said Reid at the time, not a full year into his first Senate term. “I’ve developed a great respect, even an awe, for the rules and procedures of the Senate.”

Reid continued.

“The rules are a carefully-crafted compromise designed to protect the right of a majority to prevail while preserving the right of a minority to prolong debate,” said Reid.

Some may find a paradox in Reid’s position as a freshman in 1987 and his nuclear option ploy in 2013.

During an interview with yours truly last year, Reid advocated the abolition of the filibuster. He argued it wouldn’t stand in a year. Reid was wrong about that. But there are machinations among Senate Democrats to alter the filibuster.

Most major political leaders are multi-faceted, complex figures. Reid is no exception. On one hand, there’s the Senate warrior, fighting for his party and his president. Challenging reporters and ticking off Republicans. On the other, Reid’s just a regular guy. Joking about baseball. Extolling the achievements of fellow Nevadan Bryce Harper when he played for the Washington Nationals before decamping to Philadelphia.

Not long after Harper decried a reporter’s interrogative as “a clown question, bro,” Reid mimicked the slugger. Reid lightheartedly told a reporter in the hall that his inquisition was also of the “clown question” variety.

Bro.

Reid could even be a practical joker.

Back in the 1980s, future Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, used to pal around a lot with Josh Reid, the son of Harry Reid. Reid was a member of the House of Representatives back then and lived in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. Lee’s dad, Rex Lee, worked at the Justice Department and later served as U.S. Solicitor General under President Reagan.

Both Mormon families, the Reids and Lees sometimes spent time together. And one day, as a practical joke, Reid locked the younger Lee in the garage for a few minutes. After Lee forced Reid to call a weekend session a few years ago, some who knew the story said Reid wished he hadn’t kept Lee locked in the garage.

In 2013, the government was in the middle of a 16-day shutdown over Obamacare.

It was a Saturday evening and the Senate just wrapped for the day. No end to the shutdown was in sight. I was the last reporter leaving the Capitol. As I came to the first floor elevators near the Senate Carriage Entrance, Reid materialized. He, too, was heading home. Reid knew I visited Vegas a few times by that point. I asked how he was doing and mentioned I needed a vacation once the government was funded again.

I told Reid of one of my favorite restaurants in Las Vegas: Lotus of Siam. It’s a well-known Thai restaurant located off the Strip. The restaurant is in a different location now. But at the time, Lotus of Siam occupied a spot in a run-down strip mall. The entrance to the restaurant belied the culinary magic inside. The walls were plastered with pictures of Hollywood types and rock stars, all who patronized Lotus of Siam when they visited Las Vegas.

Reid proceeded to tell me Lotus of Siam was one of his favorites, too. I asked what dishes he liked there. And with that, the Senate Majority Leader whipped out his phone dialed his wife Landra, asking for the name of a dish the two of them often enjoyed.

“Honey, what is that dish you like so much at Lotus of Siam,” Reid asked his wife. “It’s with pumpkin?”

++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Wendy Sherman was one of the most senior figures at the State Department in 2014. Sherman and other officials journeyed to Capitol Hill to lead a Senate-wide briefing in the basement of the Capitol Visitor’s Center on North Korea’s nuclear program.

TV networks positioned a bank of cameras in the Senate subway station in hopes of grabbing a few senators as they came and went from the briefing. I asked another colleague to handle the stakeout and headed to Cups, a coffee shop in the basement of the Russell Senate Office Building. My plan was to grab a cup of coffee and then cut past the subway station stakeout en route to the Capitol Rotunda. That’s where I was scheduled to meet a source.

Just as I walked up to the stakeout, Harry Reid appeared atop a small escalator leading to the subway station and near where senators would receive their briefing. I hadn’t spoken to Reid directly in a while. He waved hello. We met at the top of the escalator. I told Reid that I’d be heading to Las Vegas again in a few weeks during the upcoming Congressional recess.

We spoke for a moment, ear-to-ear. Naturally, all of the cameras at the stakeout focused on the two of us talking, as though we were exchanging important information about Pyongyang.

“Where are you staying,” Reid asked.

I told Reid we previously stayed at the Bellagio and Mandalay Bay. But we weren’t sure yet this time.

“Stay at Wynn,” said Reid, without missing a beat.

“Wynn” is a hotel/casino complex on the north end of the Vegas Strip. Casino Mogul Steve Wynn ran the place until being forced out in 2018 due to sexual misconduct allegations. Reid was telling me this years before anything was known publicly about Wynn’s alleged infractions.

Reid, being Reid, was always frank in his assessments of most situations. Even if it came to hotels on the Vegas Strip.

“Steve Wynn is an a– but a friend,” said Reid of Wynn. “But he has the nicest place in Las Vegas.”

I thanked Reid for the suggestion and headed up to the Rotunda. Reid went the other direction, toward the North Korea briefing.

By the time I reached the Rotunda, my email exploded with questions from reporters at the stakeout who spotted the escalator exchange but couldn’t hear what we were saying.

“What did Reid tell you about North Korea?” they all asked.

“Nothing,” I told them.

“Come on, Chad. What did he say?” probed one incredulous colleague.

Finally, one of Reid’s aides reached out, curious what the majority leader had said.

Reid’s staffer was just being diligent, wondering if he needed to brace for a juicy report on North Korea.

“He told me to stay at Wynn,” I replied.

No special information about Pyongyang. No intelligence on Senate parliamentary strategy. No information on Reid’s political future. Just an unsolicited hotel recommendation.

Stay at Wynn when in Vegas.

Harry Reid was one of the biggest opponents of the Washington Football Football Team – née the Redskins – and owner Dan Snyder Snyder famously told USA Today that he would “never” change the name of the team. “It’s that simple. NEVER – you can use caps.”

Reid undertook a pet project during the final years of his service on Capitol Hill. A federal court canceled the team’s trademark in 2014. That seemed to invigorate Reid. Rather than tussling with Republicans, the Nevada Democrat would routinely come to the Senate floor to personally blast Snyder and implore him to change the team name. Reid described the club as “a racist franchise,” even hoping for the team to lose games.

Considering the team’s fates of late, the Redskins probably didn’t need any intercessions from Reid.

After the “Deflategate” controversy with the New England Patriots, Reid beseeched NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell to “act as swiftly and decisively changing the name of the DC team as he did about not enough air in a football.”

Reid and other Senate Democrats crafted legislation to end the NFL’s tax-exempt status if it didn’t order a change in the team’s name.

“It is not right that the National Football League continues to denigrate an entire population,” said Reid in 2015, noting the 27 Native American tribes he represented in Nevada. “Every time they hear this name is a sad reminder of a long tradition of racism and bigotry.”

Reid predicted that eventually “the name will change.”

The team dropped the Redskins moniker a few weeks after my summer, 2020 interview with Reid.

“One of my disappointments in my senatorial tenure was the fact that we did not get this done during the time I was there,” said Reid.

Nevada officials just renamed McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas after Reid two weeks ago. The airport had been named after Sen. Pat McCarran, D-Nevada, was instrumental in aviation policy and pushed for the creation of the Air Force. But McCarran was a race-baiter, an anti-Semite and uttered a host of xenophobic tropes over the years. Thus, the McCarran name was just dropped in favor of Reid.

McCarran remains as one of Nevada’s two statues in the official U.S. Capitol collection. Reid told me years ago that the McCarran statue “should be put out to pasture.” It is generally thought that Nevada will eventually replace the McCarran statue in the Capitol with one of Reid.