Einfach Tsungen

sauber saugen.

Mit dem Zungensauger von TS1

Frischer Look für den TS1 Zungensauger

Neues Logo und Farben machen den Frische-Kick sichtbar

Total sauber mit TS1.

Zungenreinigung leicht gemacht mit dem TS1 Zungensauger

Entdecken Sie die professionelle Zungenreinigung mit dem TS1 Zungensauger in Ihrer Zahnarztpraxis! Dieses effektive Hilfsmittel wird mühelos an den Speichelsauger der Behandlungseinheit angeschlossen. Mit seiner sanften, aber gründlichen Reinigungstechnologie entfernt der TS1 Zungensauger effektiv bakterielle Beläge von der Zunge, um eine optimale Mundhygiene zu gewährleisten.

Warum Zungenreinigung in der Praxis?

- ca. 60% aller Bakterien im Mund liegen auf der Zunge (Quirynen et al.2009)

- bakterielle Zungenbeläge sind die Hauptursache für Halitosis

- zur kompletten PZR gehört auch die Reinigung der Zunge

Quirynen M. et al. Characteristics of 2000 patients who visited a halitosis clinic. J Clin Periodontol 2009;36:970-975

Intraorale Ursachen für Halitosis

Intraorale Ursachen für Halitosis | |

|---|---|

Zungenbelag | 43,4 % |

Zungenbelag + Gingivitis/Parodontitis | 18,2 % |

Parodontitis | 7,4 % |

Gingivitis | 3,8 % |

Mundtrockenheit | 2,5 % |

Zahnbedingt (Karies … ) | 0,4 % |

Candida | 0,2 % |

GESAMT | 75,9 % |

Warum der TS1 Zungensauger?

- deutlich bessere Zungenreinigung verglichen mit herkömmlichen Zungenschabern

- Tiefenreinigung der Zunge durch Absaugen bis in die Krypten

- Entfernung bakterieller Zungenbeläge aus der Mundhöhle

- kaum Würgereiz beim Patienten

- keine Traumatisierung der Zungenpapillen

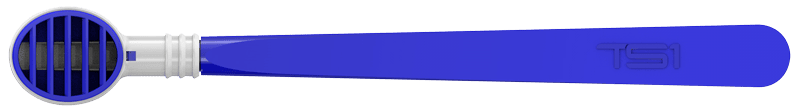

TS1 Zungensauger Lamellenseite zum Absaugen,

Noppenseite zum Einmassieren eines Reiningungsgels

Noppenseite zum Einmassieren eines Reiningungsgels

TS1 Zungenreiniger in der Praxis

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr InformationenAnwendungsgebiete

Der TS1 ist die ideale Ergänzung bei jeder professionellen Zahnreinigung (PZR, die dadurch zu einer PZR+ wird), für eine Full Mouth Disinfection (FMD) sowie für eine Behandlung von Mundgeruch.

Nur 1 Minute

bis zur hygienischen Sauberkeit

Nicht nur für Ihre Mitarbeiter ein Vergnügen: Der Zungensauger gibt Ihrer Praxis einen unverwechselbaren Benefit und Ihren Patienten professionelle hygienische Sauberkeit. Die Anwendung des TS1 Zungensaugers zur Entfernung des Zungenbelags in der Praxis bedeutet: professionelle Zungenreinigung leicht gemacht.

Die 3 Schritte zur PZR+

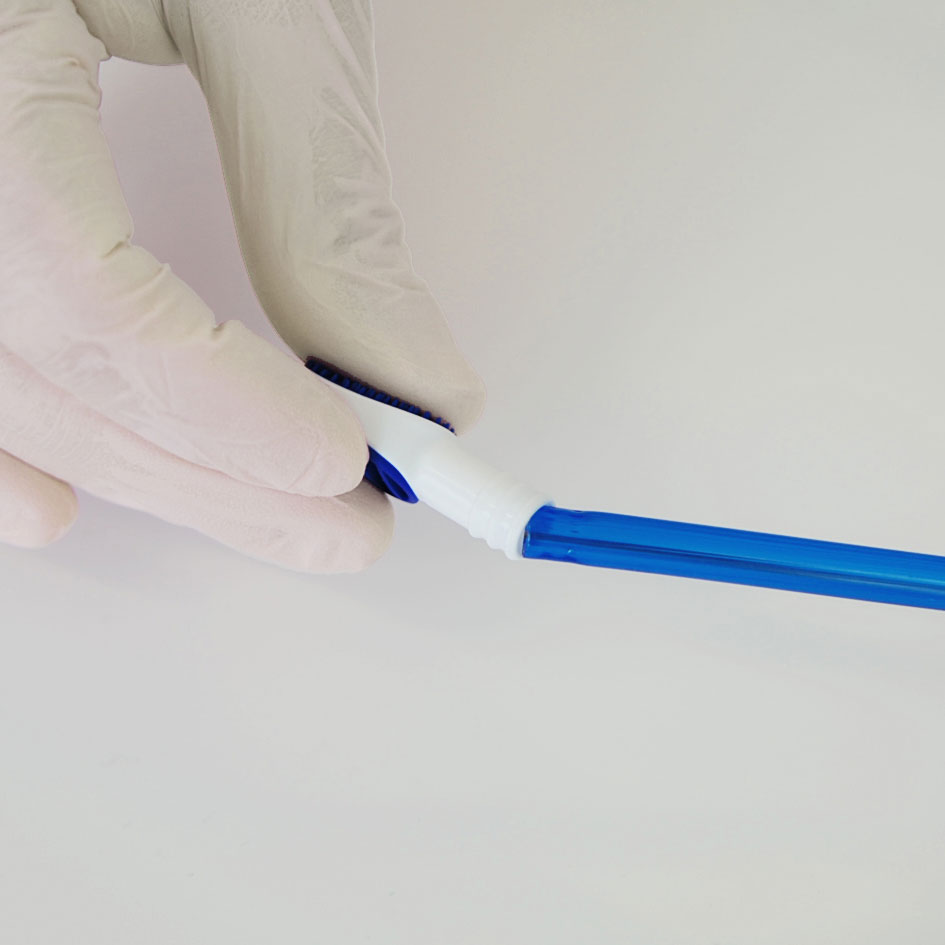

Aufstecken

Auftragen

Absaugen

Ihre Patienten

werden es lieben

Die Zunge ist wie der rote Teppich vor dem Eingang: Ein sauberer Teppich ist die Basis für eine gute Mund- und Allgemeingesundheit. Die regelmäßige und gründliche Zahn- und Zungenreinigung ist deshalb ganz einfach essenzieller Bestandteil für unsere gesamte Gesundheit.