London

CNN

—

An analysis of Pakistan’s devastating floods has found “fingerprints” of the human-made climate crisis on the disaster, which killed more than 1,400 people and destroyed so much land and infrastructure it has plunged the South Asian nation into crisis.

The analysis, published Thursday by the World Weather Attribution initiative, was unable to quantify exactly how much climate change contributed to the floods — which were caused by several months of heavy rainfall in the region — but some of its models found that the crisis may have increased the intensity of rainfall by up to 50%, when looking specifically at a five-day downpour that hit the provinces of Sindh and Balochistan hard.

The analysis also found that the floods were likely a 1-in-100-year event, meaning that there is a 1% chance of similarly heavy rainfall each year.

If the world warms by 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures — as it is on course to — short rain bursts like those seen in the five-day period will likely become even more intense. The Earth is already around 1.2 degrees warmer than it was before industrialization.

The scale of the floods and the WWA analysis highlight the enormous financial need to address impacts of the climate crisis.

“The kind of assistance that’s coming in right now is a pittance,” Ayesha Siddiqi, a geographer at the University of Cambridge, told journalists at a press conference. “A number of Western economies have argued that they’re suffering their own crises, because of the war in Ukraine and various other issues.”

She described the UK’s original assistance of £1.5 million ($1.7 million) as “laughable.”

The UK has, however, increased its pledge to £15 million ($17 million) more recently. The geographical area that is now Pakistan was part of the former British colony of India until 1947, when the British partitioned the land into two separate dominions.

Fully developed nations bear a far larger historical contribution to climate change than the developing world.

Siddiqi said that the funds coming into Pakistan paled in comparison with the assistance sent after deadly floods that hit the country in 2010.

“The big global news [in 2010] was all about ‘We must help Pakistan or the Islamists will win,’” she said, explaining that there was a fear in the West at the time that Islamist groups would take advantage of the floods’ aftermath to recruit more members. “And this time around, of course, we don’t have the same geopolitical imperative to help Pakistan, and so the aid has really been a pittance.”

Pakistan is responsible for around 0.6% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, even though it makes up nearly 2.7% of the global population, according to the European Union’s global emissions database. China is the world’s biggest emitter, at 32.5%, and while the US is second, accounting for 12.6%, it is historically the biggest emitter globally.

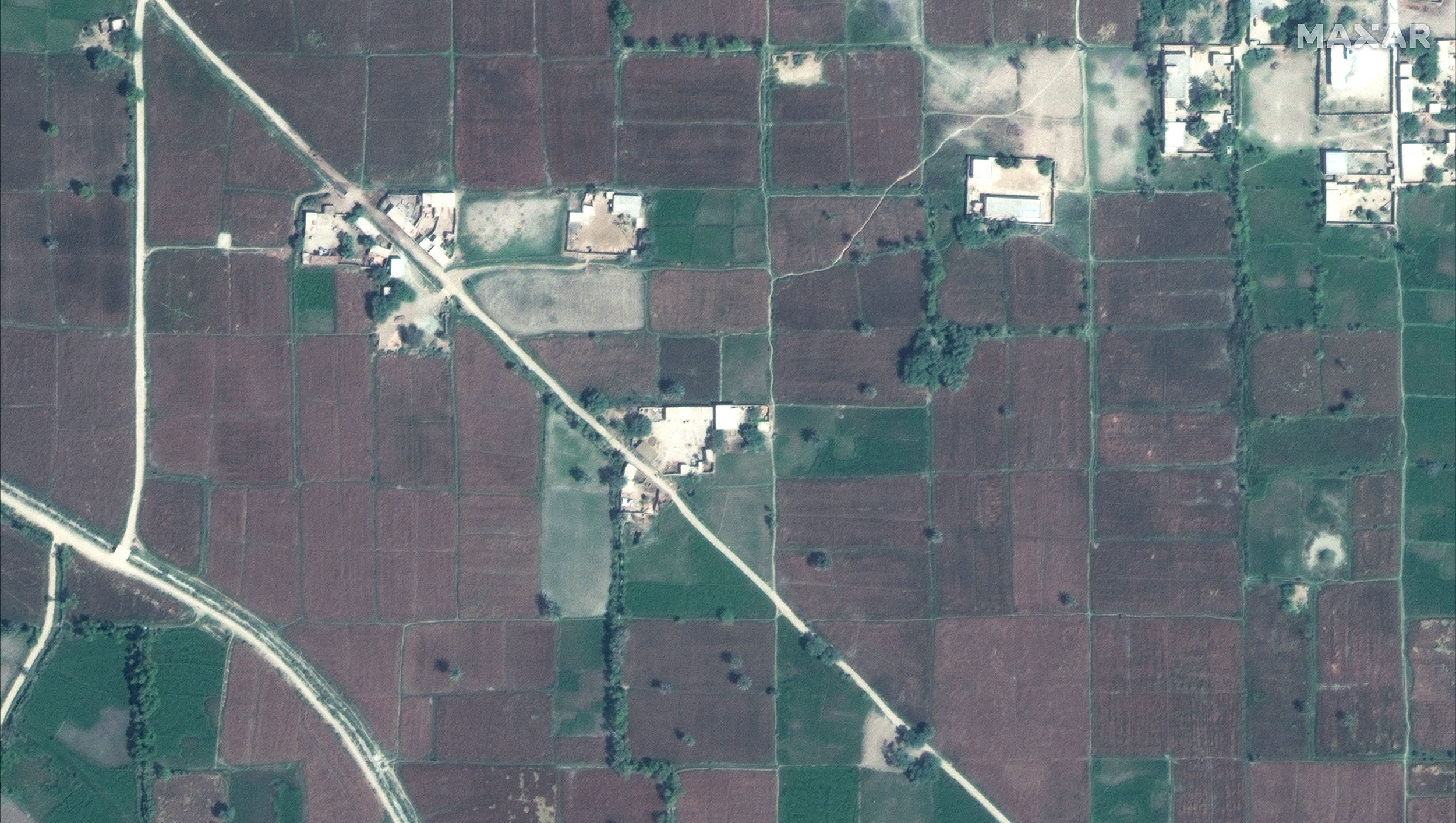

More than 33 million people in Pakistan have been impacted by the floods, which is more than the population of Australia or the state of Texas. The floods destroyed 1.7 million homes, swept away dozens of bridges and turned verdant farmland into fields of dust.

The UN estimates the recovery could cost around $30 billion, which around the same value as the country’s annual exports.

There were limitations to how much scientists could determine about the role of the climate crisis in the floods because the impacted area has such huge natural variability in rain patterns during monsoon seasons. It’s also a year of La Niña, which typically brings heavier and longer rainfall to Pakistan.

The role of climate change in heat waves — which also hit Pakistan and other parts of the Northern Hemisphere this year — is much larger and often clearer to determine in South Asia, the scientists said. A WWA study published in May found that pre-monsoonal heat waves in Pakistan and India were made 30 times more likely by climate change.

“Every year the chance of a record-breaking heat wave is higher than the year before,” said Friederike Otto, co-founder of WWA and a climate scientist with the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London.

The next heat wave in Pakistan will probably have “quite devastating consequences,” she said. “Because even if everything is done now to invest in reducing vulnerability, that takes time.”

She said that while scientists couldn’t determine exactly how much climate change contributed to the floods, it was probably closer to “doubling” their likelihood, as opposed to the 30-fold factor they found with the region’s heat wave.

The issue of who should pay for the impacts of the climate crisis, known as “loss and damage,” has long been a sticking point between developing and some developed nations, and is expected to be central to the upcoming COP27 international climate talks in Egypt.

“I think it’s absolutely justified to say, ‘We need, finally, some real commitment to addressing loss and damage from climate change,” Otto said.

“A lot of what leads to disaster is related to existing vulnerabilities and not to human-caused climate change. But of course, the Global North plays a very large role in that as well, because a lot of these vulnerabilities are from colonialism and so on. So there is a … very huge responsibility for the Global North to finally do something real and not just talk.”