NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Special Counsel John Durham argues Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann “misled” the FBI in September 2016 by “disseminating highly explosive allegations” about candidate Donald Trump on behalf of the “opposing presidential campaign,” without disclosing his connection to the Clinton campaign.

Sussmann’s actions were “capable of influencing the FBI’s decision to initiate” the Trump-Russia investigation, and its “subsequent conduct of that investigation,” Durham said Friday in a court filing.

That filing opposed Sussmann’s motion to dismiss the case against him. Sussmann has pleaded not guilty to making a false statement to a federal agent.

CLINTON CAMPAIGN LAWYER SUSSMANN FILES MOTION TO DISMISS DURHAM PROSECUTION

Durham’s indictment alleges that Sussmann told then-FBI General Counsel James Baker in September 2016 — less than two months before the 2016 presidential election — that he was not doing work “for any client” when he requested and held a meeting in which he presented “purported data and ‘white papers’ that allegedly demonstrated a covert communications channel” between the Trump Organization and Alfa Bank, which has ties to the Kremlin.

Sussmann’s lawyer’s last month argued Sussmann did not make any false statements to the FBI and claimed that the false statement alleged in the indictment is “about an entirely ancillary matter” that is “immaterial as a matter of law.”

But Durham, in his latest filing, countered that Sussmann’s false statement is legally relevant.

“The defendant’s false statement was capable of influencing both the FBI’s decision to initiate an investigation and its subsequent conduct of that investigation,” Durham wrote.

AMID RUSSIA WAR ON UKRAINE, BILL CLINTON RELAUNCHING CLINTON GLOBAL INITIATIVE

Durham wrote that Sussmann’s false statement “was anything but ancillary,” noting that the existence, or lack thereof, of attorney-client relationships “would have shed critical light on the origins of the allegations at issue.”

U.S. Attorney John Durham, center, outside federal court in New Haven, Conn.

(Bob MacDonnell/Hartford Courant/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

“The defendant’s efforts to mislead the FBI in this manner during the height of a presidential election season plainly could have influenced the FBI’s decision-making in any number of ways,” Durham wrote. Durham added that Sussmann’s argument to dismiss “conveniently ignores the factual and practical realities of how the FBI initiates and conducts investigations.”

Durham wrote that the government, during trial, will present evidence that “will prove” that the FBI could have taken “any number of steps prior to opening what it terms a ‘full investigation,’ including, but not limited to, conducting an ‘assessment,’ opening a ‘preliminary investigation,’ delaying a decision until after the election, or declining to investigate the matter altogether.”

The prosecutor noted that a “host of factors” play into the FBI’s decision whether and how to initiate an investigation, including “the source and origins of the information.”

Sussmann’s lawyers last month argued that allowing the case to go forward “would risk criminalizing ordinary conduct, raise First Amendment concerns, dissuade honest citizens from coming forward with tips and chill the advocacy of lawyers who interact with the government.”

But Durham pushed back.

“Here, had the defendant truthfully informed the FBI General Counsel that he was providing the information on behalf of one or more clients, as opposed to merely acting as a ‘good citizen,’ the FBI General Counsel and other FBI personnel might have asked a multitude of additional questions material to the case initiation process,” Durham wrote.

He noted the FBI “might have asked, for example, whether the defendant’s clients harbored any political biases or business motives that might cast doubt on the reliability of the information.”

Durham also noted the FBI “likely would have conducted additional, behind-the-scenes steps — database checks, case file searches, etc. — to assess the defendant’s potential motivations and those of his clients.”

“Indeed, it is obvious that a lawyer presenting himself as a paid advocate for a client naturally raises specific concerns related to bias, motivation and the reliability of the information being provided,” Durham wrote.

Durham, pointing to Justice Department and FBI “stringent guidelines” ahead of U.S. elections, said that the FBI may have taken a number of “different steps in initiating, delaying or declining the initiation of this matter had it known at the time that the defendant was providing information on behalf of the Clinton campaign and a technology executive at a private company.

“Accordingly, and contrary to the defendant’s argument that a tipster’s ‘motivation’ is insignificant and ‘ancillary,’ the evidence at trial will demonstrate that a person’s motivation in providing information to the FBI can be a highly material fact in determining whether and how the FBI opens an investigation and then conducts an investigation it has opened,” Durham added.

Durham also argued that “evidence will show that it would have been all the more material here because the defendant was providing this information on behalf of the Clinton campaign less than two months prior to a hotly contested U.S. presidential election.”

“In sum, the evidence will demonstrate that the defendant’s false statement to the FBI General Counsel had the capacity to influence the lawful function of the FBI as it related to the case initiation phase,” Durham wrote.

Further, Durham wrote that evidence at trial will also establish that Sussmann’s false statement “had the capacity to influence the FBI’s conduct of this investigation.”

Durham notes that had Sussmann “truthfully disclosed the fact that he represented Tech Executive-1,” who has since identified himself as Rodney Joffe, the FBI “likely would have asked certain questions and conducted interviews regarding the information’s “reliability” and the individual’s “motivation in providing the information.”

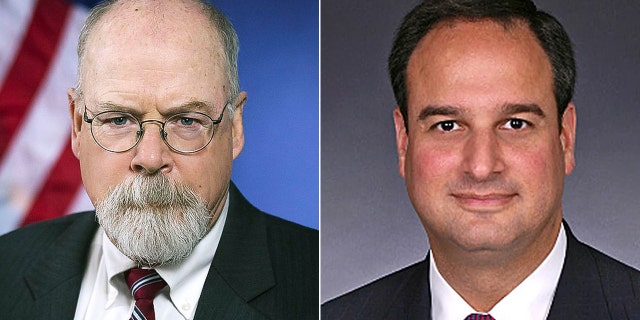

John Durham and Michael Sussmann.

(Sussmann photo from Perkins Coie)

Durham points to Sussmann’s motion to dismiss, noting that while Joffe “had a history of providing assistance to the FBI on cybersecurity matters,” during “this instance” he provided “politically-charged allegations anonymously through the defendant and a law firm that was then-counsel to the Clinton campaign.”

“Given (Joffe’s) history of assistance to law enforcement, it would be material for the FBI to learn of the defendant’s lawyer-client relationship with (Joffe) so that they could evaluate (Joffe’s) motivations,” Durham wrote.

Durham noted that the FBI may have sought to interview Joffe, which, in turn, “might have revealed further information” about Joffe’s “coordination with individuals tied to the Clinton campaign, his access to vast amounts of sensitive and/or proprietary internet data, and his tasking of cyber researchers working on a pending federal cybersecurity contract.”

“Moreover, had the FBI known that the defendant was presenting the information on behalf of even an anonymous client, rather than purporting to provide the information as a concerned citizen, they also likely would have been able to more fully investigate the genesis of the aforementioned white papers, including the role of the defendant and others in obtaining, drafting and compiling the analysis of data,” Durham wrote.

Meanwhile, in a section titled “factual background,” Durham details allegations against Sussmann, writing that Sussmann had “assembled and conveyed the allegations to the FBI on behalf of at least two specific clients,” including Joffe, “and the Clinton campaign.”

Joffe is not named in the filing but identified himself in a statement. He has not been charged with a crime.

Durham notes that Sussmann’s “billing records reflect” that he “repeatedly billed the Clinton campaign for his work on the Russian Bank-1 allegations.”

That section of Durham’s filing also alleged that Sussmann and Joffe had met and communicated with another law partner who was serving as general counsel to the Clinton campaign. Sources told Fox News that lawyer is Marc Elias, who worked at the law firm Perkins Coie.

Durham also writes that his indictment of Sussmann alleges that Joffe “had worked with Sussmann, a U.S. investigative firm retained by Perkins Coie on behalf of the Clinton campaign, numerous cyber researchers and employees at multiple internet companies to assemble the purported data and white papers.”

Elias’ law firm, Perkins Coie, is the firm the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign funded the anti-Trump dossier through. The unverified dossier was authored by ex-British Intelligence agent Christopher Steele and commissioned by opposition research firm Fusion GPS.

Sources familiar told Fox News that the “U.S. investigative firm” Durham points to in his filing could be Fusion GPS.

Durham notes that Joffe “tasked these researchers to mine internet data to establish ‘an inference’ and ‘narrative’ tying then-candidate Trump to Russia” and indicated that he was “seeking to please certain ‘VIPs,’ referring to individuals at Law Firm-1 and the Clinton campaign.”

Durham again lays out that the government’s evidence at trial will “establish that among the Internet Data Tech Executive-1 and his associated exploited was domain name system (DNS) Internet traffic pertaining to (i) a particular healthcare provider, (ii) Trump Tower, (iii) Donald Trump’s Central Park West apartment building, and (iv) the Executive Office of the President of the United States (EOP).”

Durham notes that Sussmann in February 2017 provided an “updated set of allegations,” including the Alfa Bank claims, and additional allegations related to Trump to a second U.S. government agency, which Fox News has confirmed was the CIA.

“The government’s evidence at trial will establish that these additional allegations relied, in part, on the purported DNS traffic that Tech Executive-1 and others had assembled pertaining to Trump Tower, Donald Trump’s New York City apartment building, the EOP and the aforementioned healthcare provider,” Durham writes.

He noted Sussmann allegedly provided the second government agency data “which he claimed reflected purportedly suspicious DNS lookups by these entities of internet protocol (IP) addresses affiliated with a Russian mobile phone provider.”

Durham notes that Sussmann claimed that the lookups “demonstrated that Trump and/or his associates were using a type of Russian-made wireless phone in the vicinity of the White House and other locations,” Durham wrote.

Durham added that Sussmann “made a substantially similar false statement” in his February 2017 meeting with the CIA as he did to Baker at the FBI in September 2016, asserting that he “was not representing a particular client in conveying the above allegations.”

“In truth and in fact, the defendant was continuing to represent Tech Executive-1 — a fact the defendant subsequently acknowledged under oath in December 2017 testimony before Congress (without identifying the client by name),” Durham wrote, adding in a footnote that, by February 2017, “the Clinton campaign for all intents and purposes no longer existed.”

Last month, Sussmann’s legal team demanded the court “strike” the “factual background” section of Durham’s last filing, which includes many of these allegations. They argued it “unnecessarily include[d] prejudicial — and false — allegations that are irrelevant to his motion and to the charged offense, and are plainly intended to politicize this case, inflame media coverage and taint the jury pool.”

Meanwhile, Durham notes that during Sussmann’s trial, the government expects evidence will “establish” that FBI General Counsel James Baker “was aware” that Sussmann represented the Democratic National Committee on “cybersecurity matters arising from the Russian government’s hack of its emails, not that he provided political advice or was participating in the Clinton campaign’s opposition research efforts.”

“When the defendant disclaimed any client relationships at his meeting with the FBI General Counsel, this served to lull the general counsel into the mistaken, yet highly material belief that the defendant lacked political motivations for his work,” Durham wrote.

“In any event, even if FBI personnel had been aware of the defendant’s relationship specifically to Democratic politics, it would be of no moment,” Durham wrote. “It is black letter law that materiality does not turn on the actual knowledge of investigators at the time of the false statement.”

“These issues are highly fact-laden,” Durham added.

Durham went on to state that the “expected testimony of multiple government witnesses will refute the defendant’s argument that the defendant’s false statement was immaterial.”

Durham also notes that his team expects that “current and former FBI employees will testify” at Sussmann’s trial that “understanding the origins of data and information is relevant to the FBI in multiple ways, including to assess the reliability and motivations of the source.”

“None of this is novel,” Durham wrote. “An evaluation of a source can (and often does) influence the FBI’s decisions regarding its initial opening decisions and subsequent investigative steps.That alone is sufficient to establish materiality.”

Durham, again, pointed to Sussmann’s claim that he was “not acting on behalf of any clients,” but said he instead, “hid his relationship with clients who harbored political and business interests tied to allegations against a then-presidential candidate.”

Durham added that the false statement was made to the FBI “as it carried out its functions of receiving and investigating national security threats.”

“The defendant’s false statement thus plainly could ‘adversely affect’ the FBI in its ability to perform this important function,” Durham added.

As for Sussmann’s lawyers argument that the case raises First Amendment “concerns,” Durham notes that federal law regarding false statements “does not police harmless untruths or ‘white lies,’ but instead targets materially false statements to government agencies.”

“False statements under Section 1001 merit no First Amendment protection because the statute is necessary ‘to protect agencies from the perversion which might result from … deceptive practices,” Durham wrote.

Durham described Sussmann as a “sophisticated and well-connected lawyer” who “chose to bring politically-charged allegations to the FBI’s chief legal officer at the height of an election season.

“He then chose to lie about the clients who were behind those allegations,” Durham wrote. “Using such rare access to the halls of power for the purposes of political deceit is hardly the type of speech that the Founders intended to protect.”

Durham has indicted three people as part of his investigation: Sussmann in September 2021, Igor Danchenko in November 2021 and Kevin Clinesmith in August 2020.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Danchenko was charged with making a false statement and is accused of lying to the FBI about the source of information he provided to Christopher Steele for the anti-Trump dossier.

Kevin Clinesmith was also charged with making a false statement. Clinesmith had been referred for potential prosecution by the Justice Department’s inspector general’s office, which conducted its own review of the Russia investigation.

Specifically, the inspector general accused Clinesmith, though not by name, of altering an email about Trump campaign aide Carter Page to say that he was “not a source” for another government agency. Page has said he was a source for the CIA. The DOJ relied on that assertion as it submitted a third and final renewal application in 2017 to eavesdrop on Page under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).