In March 2020, Chalese Smith, the single mother of a toddler and a three-year-old, was working at a 7-Eleven while pregnant with her third child.

When Smith learned that as an essential business the store would stay open as the coronavirus began circulating, she was relieved. Standing behind the register wasn’t what she wanted to do, but the job always paid enough to maintain her bills.

But soon after, her children’s daycare closed and she never returned to the 7-Eleven.

Smith eventually lost her apartment and car. Her family has stayed in two homeless shelters. She’s had around 10 jobs since COVID-19 came to Delaware, none that have afforded her the flexibility she needs to get her three children to and from daycare and school and the pay to counter costs that are rising everywhere.

“It’s taken a toll on me because it’s been so long now,” Smith said.

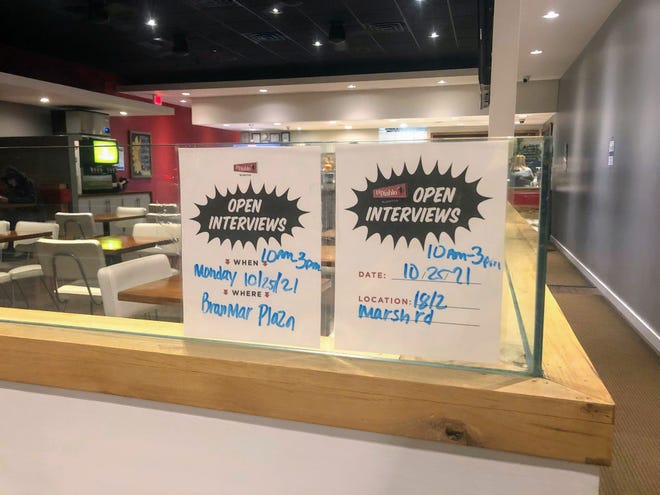

PREVIOUS REPORTING: Delaware businesses are still finding it challenging to fill out their staffs

Delaware has recovered all of the jobs lost at the start of the pandemic – in fact, 6,500 more people are employed today than in February 2020. “The Great Resignation” has given way to record workforce participation – almost half a million Delawareans were employed or seeking employment in April, according to state data.

But what the numbers fail to capture are the disruptions still felt in the everyday lives of Delawareans whose situations were upended by the pandemic response and have yet to land on solid footing.

“Looking for a job is a full-time job itself,” said Laurie, a Wilmington-area resident who has been searching for the past two years and asked to be referred to only by her first name for fear of impacting her job prospects. “It’s emotionally draining.”

Laurie left an accounting job at a hearing aid company in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania in 2018, feeling “overworked, underpaid and underappreciated.” After taking time off, she started looking for work again the following year, but didn’t find the roles and pay to her liking.

Laurie’s job search accelerated when COVID-19 prematurely ended her husband’s temporary assignment at Wawa headquarters in Media, Pennsylvania. In the last two years, dozens of her job applications have gone unanswered. In interviews, she’s sometimes dinged for a lack of experience.

With offices short-staffed, the jobs she’s been offered ask her to cover multiple roles.

“Unless you’re paying two, three, four salaries, forget it,” she said.

Laurie and her husband rented a home behind Fairfax shopping center for nine years. As the housing market heated up, the homeowner decided to sell. They bounced between hotels and the homes of friends and family for months before finding another rental.

Her husband now works full-time for CSC and spends his nights working at the 2SP Tap House in Chadds Ford.

“Eventually you get through it and we’re slowly getting there,” Laurie said. “But last year was hell.”

“Help wanted” signs still pervade businesses across the state, pointing toward an enduring disconnect between the roles, hours and pay offered by employers and desired by job seekers. Those that spoke to Delaware Online/The News Journal are also increasingly wary of accepting work far from home with gas prices around $5 per gallon.

The sectors that have lagged the farthest behind pre-pandemic hiring levels are leisure and hospitality and education and health, according to state data.

With a bachelors degree and 28 years experience working for the state, Shelley Nealle never thought her job hunt would last as long as it has.

When Autism Delaware made cuts at the beginning of the pandemic, Nealle was let go. She worked with the organization for two years following her career with the state, which made her one of the last ones in the door and the first one out.

PREVIOUS REPORTING: As the pandemic approaches third year, Delaware businesses still face staffing challenges

DIVE DEEP: State law prohibits pregnant prisoners from being shackled during labor. Is it followed?

She collected unemployment insurance for three months before starting her Lewes job search.

“I never really worried about it,” Nealle said.

Two years later, she’s yet to find suitable work in her field.

At one point, Nealle was up for a job as a social worker. When she didn’t get the job, Nealle was confused: she used to manage 25 of the state’s social workers.

Nealle took on a handful of restaurant jobs and eventually landed at the real estate company Coldwell Banker. There, she realized the cleaning crews were making over $20,000 more than she was at the reception desk. So she got a business license to clean rentals this summer. It’ll complement her restaurant gig.

Nealle said she’s started to see more postings in her field in the past two months that she will pursue after the summer.

“I’ve been on Indeed for two years,” she said.

Smith, the single mother of three, will start two jobs this week with Family Dollar and SafeLink Wireless.

She has a car now, which she hopes will make it easier to juggle the jobs with the needs of her now 18-month-old, three-year-old and five-year-old kids. The kindergartener is in summer school because she missed too much school.

Last week, Smith posted on Facebook a graphic with the title “Weekly Schedule.” Listed with each day of the week is “HUSTLE.” Below it, the footnote reads, “You can’t have a million dollar dream with a minimum wage work ethic.”

When she’s out with her children, they’ve begun to ask when will they go home.

She tells them that the shelter is not their home. It’s just a place they’re staying for the time.

Contact Brandon Holveck at bholveck@delawareonline.com. Follow him on Twitter @holveck_brandon.