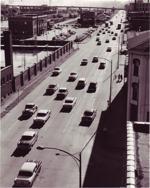

Davenport is considering making 3rd and 4th streets, shown from River Drive, two-way in fiscal year 2024.

When Dan Bush had an office on 3rd Street in downtown Davenport, he and others in the office would often joke they should take a shot every time someone drove the wrong way down the one-way.

“And most days, we would have had a solid buzz by lunch,” said Bush, co-owner of Analog Arcade Bar, Armored Gardens and Devon’s Complaint Department.

Davenport aldermen will meet for a work session Tuesday afternoon at City Hall to discuss a proposal to eliminate one-way traffic through part of downtown.

Davenport’s proposed six-year capital improvement plan includes $1.7 million budgeted in fiscal year 2024 to convert the traffic signals on 3rd and 4th streets to allow for two-way traffic from East River Drive to Marquette Street. The Downtown Davenport Partnership would contribute $600,000 toward the cost of the project.

People are also reading…

Here’s what you need to know ahead of the meeting.

What’s being proposed?

The city’s proposed new annual budget includes $100,000 for engineering services as part of an overall $9.2 million project spread out over the next two fiscal years and funded with a $7.3 million federal grant for the rehabilitation of 3rd and 4th streets from Telegraph Road to Harrison Street.

As part of the design process, the Downtown Davenport Partnership has requested the city incorporate DDP’s proposed two-way street implementation as part of the planned reconstruction.

Plans developed by the downtown partnership would make 3rd and 4th streets a single lane in each direction with a center turn lane and a bicycle lane and curbside parking on each side of the street.

Why the change?

The partnership and some city officials note downtown Davenport has changed considerably in recent decades, with the addition of roughly 1,400 apartment units over the past 20 years.

As such, they argue the interstate-width streets move traffic at unsafe speeds through a downtown that’s become increasingly residential and create dangerous intersections.

More than 2,000 residents now live downtown in 1,600 units, with another 400 apartment units planned.

Multiple independent traffic studies and master plans for downtown development have questioned or called for the outright removal of one-way traffic downtown dating back to 1986.

Touted benefits of converting portions of downtown’s most traveled one-way thoroughfares to two-way streets include:

- Improved safety and quality of life for downtown residents, visitors and businesses. While the speed limit would remain the same, two-way streets would calm and slow existing traffic and promote a more pedestrian- and bike-friendly area where more people live and congregate

- More people walking and biking through downtown would make restaurants and storefronts more visible and accessible to customers, making downtown sites more marketable for development with a more walkable downtown. DDP Executive Director Kyle Carter said a major grocery chain recently turned down a development opportunity on 4th Street, adjacent to the new YMCA, and specifically cited one-way traffic as being problematic for their business and its access.

- Opportunities to expand outdoor seating for restaurants and retail and would make driving downtown less confusing for visitors, with faster access to key downtown amenities and hotels.

- Use of 4th Street as a primary flood detour route connecting the west end to downtown and East Village during flooding. Doing so, though, requires two-way traffic for the detour to function properly and efficiently.

A 2014 University of Louisville study of a small area of the Kentucky city found converting from one-way to two-way streets led to reduced speeds, fewer collisions and even better property values and lower crime.

In addition, other cities in Iowa that have had one-ways for decades, like Des Moines, Cedar Rapids and Muscatine, have successfully put two-way streets in their downtowns. And last week, Peoria, Ill., announced it would spend $14 million to transform downtown streets into two-ways.

“Just like the race in the 1950s to build one-ways, there’s a new race to meet modern needs to undo them, particularly in smaller cities that lack serious congestion and high traffic counts,” according to the DDP.

Carter

What’s the traffic volume and will it cause congestion?

Traffic counts on 3rd and 4th streets through downtown have changed little over the past 15 years.

According to Iowa Department of Transportation traffic counts from 2006 to 2018 (the most recent year for which data is available), peak average daily traffic along 3rd Street is 11,000 and 9,300 along 4th Street, with less volume east and west of the downtown core.

In addition, DDP notes River Drive (U.S. Highway 67) functions as a bypass route for the downtown.

“If both streets exceed 15,000 vehicles per day with no reasonable bypass route, then the conversion may increase congestion,” according to a DDP traffic study.

Traffic and shopping patterns downtown as well have fundamentally changed since 3rd and 4th streets were converted to one-ways in 1954, with Brady and Harrison streets following suit in 1972 to 1973, Carter said.

In the 68 years since the streets were turned into one-way thoroughfares, departments stores once clustered downtown have moved north or shuttered. And with the advent of ATMs and the internet, needing to drive downtown to go to the bank is a thing of the past. So too is the need to accommodate a high volume of workers commuting through downtown to the west end to work at factories along the riverfront that have either shuttered or moved north to the city’s fringes.

“Traffic calming and a focus on pedestrian-level development is now more important than non-existent traffic congestion and a misguided race to keep up with the suburbs,” DDP wrote in its defense of two-way streets.

What about deliveries and emergency vehicles?

Dan Pekios of Davenport operated the Source Book Store at 232 West 3rd St. for 22 years.

Pekios said he worried converting 3rd and 4th streets to two-way traffic “will be a disaster” for the ability of downtown businesses to get deliveries and the movement of emergency vehicles.

He said delivery trucks were constantly parked in the street, “which is no problem as there is plenty of room to go around them.”

“They cannot park in the alleys as these are one lane and would block all the business and tenant parking lots,” Prkios said. “And many of the buildings do not have an alley.”

DDP Director Carter and downtown business owners, however, note the two-way conversion would be similar to 2nd Street, and are unaware of truck delivery issues for businesses along the street.

Pekios, too, questioned whether two-ways would be safer, as “you only have to look one direction when crossing” a one-way street.

How wide would the street be?

Street width should be sufficient to accommodate two-way traffic and on-street parking, according to the DDP. The typical width of 3rd Street and 4th Street is 55 feet.

That would accommodate two moving lanes of traffic with a dedicated left-turn lane, two dedicated bike lanes, and parallel parking along both sides of the street.

What do downtown business owners have to say?

Bush

Bush said he felt two-way streets “are far better for a flourishing” downtown.

“One-ways create a pass-through … and people don’t really stop in between,” he said. “Two-ways make downtown more walkable and safe and make buildings that previously didn’t have a retail purpose able to have retail purposes. There is a reason retail doesn’t really exist on 4th street, and this is because it’s too busy. It’s a pass-through. Making the area walkable is so crucial to a flourishing downtown.

“Urban living is not meant for fast cars. It’s meant for walking to several places in the same evening. That’s what helps grow a really positive business and living environment.”

Andrew Lopez, co-owner of Lopiez, echoed Bush.

“There are going to be a lot of growing pains … but I think in the long run it’s going to pay off for everyone in the downtown area,” Lopez said. “I think the two-way traffic will help bring in a little more business and help cars slow down and see what’s going on in this corner of downtown Davenport and will be more safe.”

Every month, he said he witnesses three to four accidents in front of the business’s location near the intersection of 3rd and LeClaire streets.

“And every day we see three to four cars go down the one-way the wrong way,” Lopez said. “I think the main goal for me is the safety of pedestrians. I see people going 60 miles an hour or faster and it’s not helping anyone around here, especially at our intersection. Like any growing city there’s going to be things people don’t’ want to change, but that we need to change … to expand the community in a way that makes sense for all of us.”

What about others?

Davenport resident Dale Gilmour urged city officials at a recent city council meeting to separate the DDP’s “propaganda from the actual facts.”

Resident Bill Handel said while he agreed with DDP’s diagnosis, he disagreed with the cure.

“We’re a different city than we were in 1954 or 1955 when the one-ways were put in,” Handel said at a recent City Council meeting. “We had lots of traffic … and we had a number of factories against the riverfront, and when those people went and returned from work, they needed something to drive on that was efficient. And the 3rd and 4th street conversion to (one-way traffic) did it. But now we don’t have that issue. The traffic counts are way down from what they were.”

But while the one-ways are overly wide and encourage excessive speeding, “I think many are skeptical of the proposed solution.”

Instead, Handel suggested the city instead narrow the roadways to two lanes, while keeping one-way traffic downtown.

Photos: Historic Downtown Davenport

Downtown Davenport street scenes at night April 11, 1954. From the archives of the Quad-City Times.

Downtown Davenport street scenes at night April 11, 1954. From the archives of the Quad-City Times.

Downtown Davenport street scenes at night April 11, 1954. From the archives of the Quad-City Times.

Downtown Davenport street scenes at night April 11, 1954. From the archives of the Quad-City Times.

Ripley St. & W. 3rd St., Davenport. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

3rd & Ripley, Davenport. Photo taken May 19, 1956. (Photo by Phil Hutchison/The Daily Times)

Roy Booker

Downtown Davenport. Photo taken June 19, 1958.

Roy Booker

The Davenport Chamber’s Traffic Committee has recommended that Ripley Street be closed from West 6th Street to the top of the hill. Members say the street is narrow and visibility at the crest is extremely limited. Published Dec. 6, 1970. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

This stretch of trees and bushes along East River Drive in Davenport may fall under the axe to provide a clear view of the Mississippi River. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

The heart of downtown Davenport looking West on 2nd Street during a summer day in the early 1930s.

East Locust Street between Pershing Avenue and Iowa Street, Davenport. On left, Lorenzen Market, 312 E. Locust St.; Guy Drug, 314 E. Locust St.; and Hawkeye Tavern, 328 E. Locust St. (Quad-City Times Archives)

Roy Booker

Vale Apartments. (Photo by Phil Hutchison/The Daily Times)

Roy Booker

Downtown Davenport. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

Handwritten on back: 3rd looking west from Perry. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

Handwritten on back: 3rd St. looking east from Ripley. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

Handwritten on back: Cutting pole on base. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

East River Drive, Davenport. (Photo by Quad-City Times)

Roy Booker

Handwritten on back: Brady St., Davenport. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

Parking Garage, downtown Davenport. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

E. 3rd St. & Pershing Ave. looking east. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

E. 3rd St. & Perry St., Davenport, looking east. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

W. 3rd St. & Western Ave., Davenport, looking east. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

W. 3rd St. & Scott St., Davenport, looking east. (Photo by Quad-City Times)

Roy Booker

W. 3rd St. & Ripley St., Davenport, looking east. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

E. 2nd St. & Brady St., Davenport, looking west. Scharff’s Department Store on left. M.L. Parker Company on right. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

E. 3rd St. & Brady St., Davenport, looking east. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

W. 2nd St. & Scott St., Davenport, looking west. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

E. 2nd St. at the Government Bridge, Davenport. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

View of downtown Davenport from the Mississippi River. Former Davenport Bank & Trust Co. tower can be seen in the background and Dillon Fountain. (Photo by Times-Democrat)

Roy Booker

East River Drive and Mississippi Avenue, Davenport. (Photo by Quad-City Times)

Roy Booker