DETROIT — Two of the men convicted of plotting to kidnap Gov. Gretchen Whitmer hired a private investigator to go to a juror’s workplace and investigate the juror’s potential bias, according to a newly unsealed court filing.

The men — Adam Fox of Michigan and Barry Croft Jr. of Bear, Delaware, who were found guilty last month of planning to kidnap the governor over her COVID-19 policies — hired the investigator to track down the juror’s co-workers to determine if the juror was biased against them. The investigation was part of a broader effort by their defense attorneys to get a new trial.

The defense long maintained this was a case of entrapment and vowed a vigorous appeal, which right now appears to focus on a potentially problematic juror who surfaced on the second day of the trial. The juror was allowed to stay on the case after the judge interviewed the person and concluded there was no proof of bias.

A misconduct tip was initially made by one of the juror’s co-workers who claimed the juror wanted to be part of the jury and intended to “hang” the defendants if picked, court filings show. But the information was secondhand. The defense hired an investigator to examine the juror and find firsthand information from the juror’s colleagues.

The investigator tracked down two co-workers who made new allegations against the juror. But the person who allegedly heard potentially bias statements firsthand won’t speak, court records show.

Still, the defense suspects foul play and argues a new trial is warranted “based on the misconduct of and the appearance of judicial bias which impacted the proceedings.”

Fox and Croft are scheduled to be sentenced in December.

This week in extremism:Fed shooting coverup, Michigan governor kidnapping case

How allegations of juror misconduct unfolded in the Whitmer trial

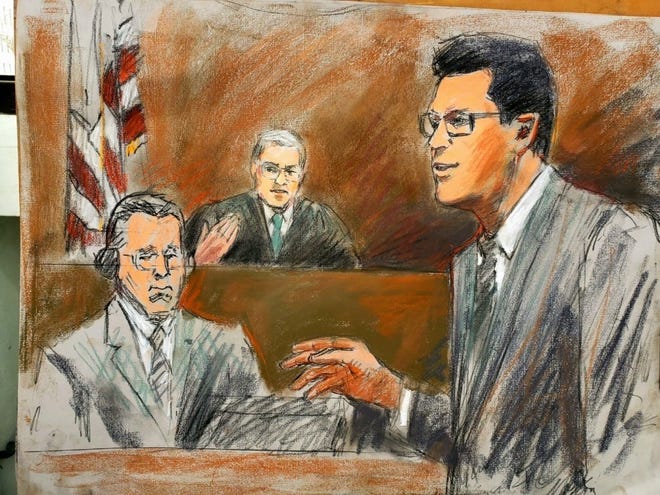

In seeking a new trial Tuesday, the defendants asked the judge for a so-called Remmer hearing — a proceeding to determine whether juror bias occurred. That filing was initially sealed, as required under a prior court order, though U.S. District Judge Robert Jonker unsealed it Thursday, with redactions.

The identity of the juror remains confidential.

On Aug. 10, the day after opening statements, the defense got a tip from a juror’s co-worker that the juror had been telling people at work that they were hoping to get on the Whitmer trial and intended to “hang” the defendants if picked.

That evening, the defense informed the judge about the allegation and asked if they could interview the juror, though the judge refused.

Instead, the judge spoke to the juror privately in his chambers — along with two court staffers — in a seven-minute interview that ended with the judge concluding the juror was not biased and could continue to hear the case. The juror denied telling co-workers they believed the defendants were guilty. The judge took the juror at their word.

The defense wanted to be included in that interview, but the judge said no. The burden is on the defense to prove juror bias, but they argue they’ve been denied the avenue to do just that.

The defense argued it was entitled to a hearing regarding juror misconduct during the trial, stressing the Sixth Amendment guarantees a defendant a trial by an impartial jury.

First tipster goes silent

After allowing the juror to remain on the panel, the judge noted the person who first contacted the defense was unwilling to identify the person who heard the alleged statements firsthand from the juror.

According to the investigator who interviewed this tipster more than once, this person got quiet over time, “stating that he has a fear of negative employment consequences” if he continued to talk about the verdict.”

The tipster also told the investigator that “if he is compelled to talk about (the juror), he will now say that he does not know anything.”

The defense maintains that had the judge ordered a Remmer hearing early on, more information could have been compelled from the tipster.

But that didn’t happen. So the defense hired a private eye to dig up information it hopes will save Fox and Croft.

A second co-worker talks

On the morning of Aug. 23, the day the guilty verdicts came down, defense investigators identified another co-worker of the potentially problematic juror who provided similar allegations as the first tipster.

But tipster No. 2 also heard things secondhand, alleging he heard from someone else that the juror intended to get on the jury to convict the defendants.

The second tipster, however, provided the name of the person who heard this firsthand. And the defense investigators tracked that person down.

Private eye tails juror’s coworker

After defense investigators identified the employee who they were told might have firsthand knowledge of the juror’s bias — identified in court records as Person No. 3 — they waited near the employee’s car and attempted to question them about the incident. The person declined to be interviewed and said they didn’t know anything.

While waiting for Person No. 3 to get off work, the second tipster told investigators the juror’s family member announced at work that day that their relative had reached out during deliberations and stated that “the jury had reached a verdict but that it had not been delivered in court yet.”

Defense lawyers argue this communication was in “clear violation” of the court’s instruction forbidding jurors to speak to anyone about the case or disclose the status of voting.

Contact Tresa Baldas: tbaldas@freepress.com