The date: January 28, 1972. The occasion: a White House gala celebrating the 50th anniversary of Reader’s Digest magazine. The entertainment that night: the wholesome Ray Conniff Singers. The president quipped, “And if the music is square, it’s because I like it square!”

But what happened next was anything but square.

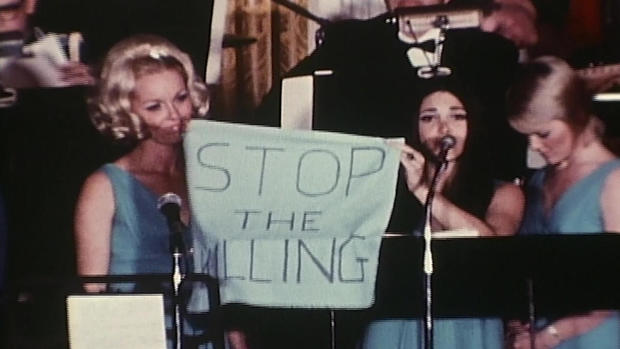

One of the women on stage held up a sign reading “Stop the Killing,” and said, “President Nixon, stop bombing human beings, animals and vegetation. You go to church on Sundays and pray to Jesus Christ. If Jesus Christ were here tonight, you would not dare drop another bomb. Bless the Berrigans and bless Daniel Ellsberg.”

The woman who stunned President Nixon and the star-studded audience with a plea to end the war in Vietnam was Canadian-born Carole Feraci.

CBS News

She told Rocca she spoke directly to Nixon, who sat in the front row, frozen. “He had a frozen smile. He did not know what to do!

“I folded up the sign, and I stood there. And I thought, ‘Hmm, okay. Let’s see what happens now.’ And he gave the downbeat for ‘Ma, He’s Makin’ Eyes At Me.’ Could it have been a more perfect song? No!”

When the music stopped, Ray Conniff apologized, and Feraci was asked to leave. She did so graciously.

Rocca asked, “The war had been going on under the Johnson administration, so what specifically was your objection to Richard Nixon’s handling of it?”

CBS News

“My objection was he could’ve stopped it at any time,” Feraci replied. “And he kept telling people there were all these reasons why it couldn’t happen, and we were winning. It was just one lie after another. We could’ve gotten out of that war the next minute. Only because of him and people like him were we still doing these atrocities to children and women and the planet.”

Feraci said that standing up to the leader of the free world came naturally to a girl who’d grown up in a rough Toronto neighborhood.

“Was this characteristic of you?” asked Rocca.

“Always. My whole life. I’ve been in trouble my whole life!” she laughed. “The good trouble!”

“And you didn’t surprise yourself there? It just came naturally to you?”

“Yeah, right.”

“Would you have considered yourself political at that point?”

“No, no,” she said. “I just cared about people’s feelings. And I knew how wrong that was. I couldn’t go for it. I just said, no way.”

As for that strong sense of right and wrong? Feraci said that was instilled in her during Sunday school at the Salvation Army: “I was a member of the Army of Christ on the planet. And it was my duty to protect people and to help as much as I could. And I did. Any friend of mine didn’t have to worry about being beat up, going or coming from school. Because I protected everybody. I was a mean little kid. I could beat anybody up!”

Feraci had been a staple on TV variety shows in the 1960s. A sought-after backup singer, she’d performed alongside the Smothers Brothers, Johnny Mathis and Frank Sinatra.

But the incident in the East Room made her a headliner. In 1972 she told CBS News, “One of the women asked me, how could I come to somebody’s private home and create a fuss? And I said to her, ‘You know, I’m sure that in the time of Jesus Christ, there were lots of people that said, Look, if you don’t like it here, why don’t you go back up to heaven with daddy up there and, you know, just leave us alone? We’ve got to change it, and that’s what I’m doing.”

Her speech made headlines around the world.

CBS News

Rocca asked, “Did you expect this kind of press coverage?”

“No. Actually, I didn’t. I hadn’t thought beyond what I was going to do,” she said.

Her one-night-only run at the White House changed her life forever. Feraci said, “The calls that came into the house, I mean, every two minutes that phone rang. And a lot of it was, ‘We know where you live, you won’t last the night. We’re gonna come and kill you.’ There were a few ‘Rah-rah for you,’ but a lot of it was, ‘You’re in deep trouble.'”

How did she deal with the threats? “Well, I hung up on a lot of them, you know? How do you deal with it? You don’t. I mean, it wasn’t Earth-shattering; it was nerve-wracking. But I went on.”

Today, at age 81, Feraci hopes what she did that night 51 years ago still resonates. When asked who she hopes hears her message today, she replied, “People like me, ordinary people like me, who realize their voice is just as powerful as anybody else’s. All they have to do is use it.”

“You make it sound simple,” said Rocca.

“It is. Duhh. It is! Speak your mind!”

CBS News

Story produced by Kay Lim. Editor: George Pozderec.