Crown

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

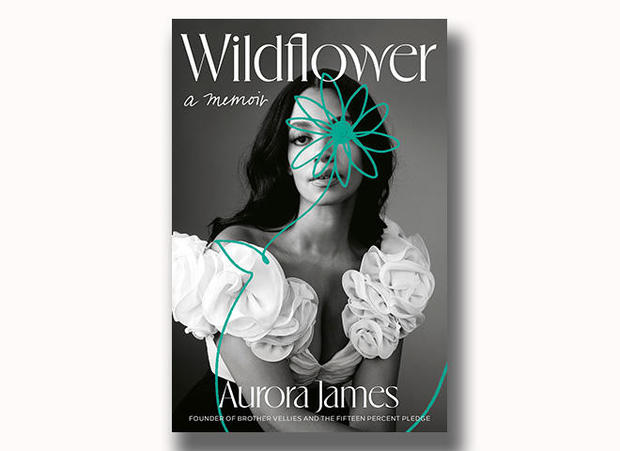

In her new memoir, “Wildflower” (published May 9 by Crown), designer, fashion entrepreneur and activist Aurora James writes about how she found an inspiration for her Brother Vellies shoes in a medina in Marrakesh, Morocco.

Read the excerpt below, and don’t miss Alina Cho’s interview with Aurora James on “CBS Sunday Morning” May 7!

“Wildflower: A Memoir” by Aurora James

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

It was the summer of 2010, I was in my mid-twenties and ready for a change of scenery and decided to move to New York. I was not sure what my next career move would be, but I knew I had a better chance of discovering it there. I found an apartment in Bed-Stuy on Craigslist and moved in, sight unseen. I also started dating a photographer I had met on a Woolly Pocket shoot named Jason. He was from Kansas and six feet tall with blond hair and blue eyes. Super kind and soft-spoken with a slight stutter, he was an assistant to several fashion photographers, including Steven Meisel and Ruven Afanador. Jason was talented, hardworking, and deeply immersed in fashion, and his ambition matched my own.

I knew my savings would not last long, so I cold-emailed a casting director named Jennifer Starr and started assisting her on Ralph Lauren, Gap, and Calvin Klein campaigns to pay my rent. It meant long hours in a big city, but I loved every moment of it.

I also agreed to do freelance work for Gen Art again connecting up-and-coming designers with sponsors to create shows during New York Fashion Week. That sometimes meant visiting stores like Opening Ceremony and scouring social media and blogs in search of young creative talent who would benefit from support….

Meanwhile, I was still thinking of what I wanted to do. Freelance fashion work was a great way to get my feet wet and pay rent, but I was still searching for what would drive me. I was also experiencing an intense pull toward Africa.

My mom had somehow acquired a time-share in Marrakesh. She still loved traveling when she could, and passed that wanderlust on to me. Jason and I saved two thousand dollars and went for two weeks. It was my first trip to a continent that felt so big to me, emotionally and physically. I had been thinking more and more about my father, and my own Ghanaian roots.

Morocco was sensory overload: Beautiful shades of terra-cotta, mustard yellows, warm browns, sky blues, and sage greens kaleidoscoped with the intoxicating smells of cinnamon, cumin, turmeric, and peppermint. Add the brass and metal elements—from doorknobs and knockers to bells and belts—and I was like a kid in a candy store. It was different from anywhere I had been before.

I could, and would, sit for hours in different carpet sellers’ stalls as exquisitely designed rugs were unfurled in front of me, each from a different region, time period, or group of artisans. Some were simple white lambswool with brown diamond shapes, others had bright red backgrounds with purple, orange, and yellow patterns. Each told a very specific story, which the sellers would excitedly share as they poured me mint tea, giddy to have a visitor as eager to understand the cultural history of these items as they were to tell it.

It was also here where I fell in love with the babouche. I first noticed the slipper-like shoe when I saw a group of men scurrying into a mosque in the medina, the marketplace at the city’s epicenter. These men, elegantly dressed in their djellabas and caftans, would quickly slip off their shoes before going in to pray. I looked at the lines of soft leather slippers and saw that the back heels were all pushed down, as if they had been stepped on. It made sense: Muslims pray throughout the day, so they need a shoe they can slip on and off with ease. I thought about all the items my mother had collected over the years, how often clothing had a purpose that extended well beyond its beauty. When form and function marry, something as simple and beautiful as the babouche is born.

I started looking for the shoes everywhere, in the markets and shops, on people. Often, I could see the back heel was steamed down, giving it a mule-like effect. Some, however, were sewn or glued down. On the streets flashier versions were trendy, but I was drawn to the sun-faded suedes that were dyed naturally, creating dusty rose and terra-cotta hues. I began buying pairs, not even checking to see if they would fit me. I simply wanted to appreciate them. No two were identical as each pair was handmade, and yet, they all shared the same easy-on-and-off effect. I loved the way a person’s daily rituals would become blended into their wardrobe, so that little style details become ingrained in a culture, handed down from ancestors. Proof of life and a rite of passage.

Of course, among the babouche, Moroccan rugs, copper teapots, and mosaic tiles for sale in the medina, there were also a lot of Ed Hardy T-shirts and True Religion jeans. Western influence was always seeping through. But before we left Morocco, I traveled deep into the medina in search of the babouche craftsmen themselves, to watch them meticulously cut and sew. I asked one of my favorite vendors for his contact info to keep in touch. I had the vague idea that I might open a store in the East Village to sell a variety of things that I discovered during my travels, like the babouche.

Back in Brooklyn, I wore my babouche around the house and to get coffee in the neighborhood and started to think about what design elements I might want to change to adapt the shoe to New York City life. I began sketching in a notebook, taking some of my babouche apart and making tweaks so that they hugged the foot a little bit better. I added additional padding to the insole and even toyed with adding a heavier outsole too. As I sketched, I realized that this modified babouche was precisely the type of thing I wanted to offer in my dream store. So I reached out to the Marrakesh vendor and requested he make me a special pair out of denim. He asked me to send him material, and I responded, “Can you find an old pair of jeans and use those?”

The first pair was not quite right, and I asked for more tweaks, communicating via WhatsApp with my sketches and mediocre high school French. He sent four or five different samples, every pair a slight variation, as he was working to find what he thought I meant. Each one got a little closer to what I envisioned. I finally asked him to place the denim seam down the center of the shoe. He did, and I did not know it then, but that would become a prototype of my first Brother Vellies shoe.

From the book “Wildflower: A Memoir” by Aurora James. Copyright © 2023 by Aurora James and Bruised Fruit LLC. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“Wildflower: A Memoir: by Aurora James

Buy locally from Indiebound

For more info: