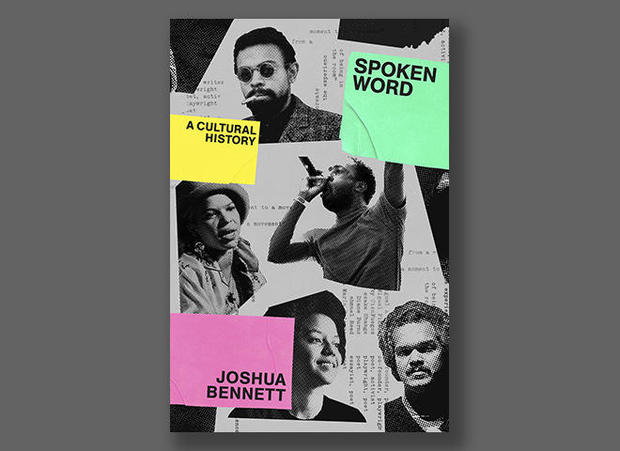

Knopf

We may receive an affiliate commission from anything you buy from this article.

In “Spoken Word: A Cultural History” (Knopf), Joshua Bennett looks back on the development of this vibrant form of poetry, encompassing diverse voices at verse gatherings, slam competitions, and the influence of social media.

Read an excerpt below:

“Spoken Word: A Cultural History” by Joshua Bennett (Hardcover)

Prefer to listen? Audible has a 30-day free trial available right now.

It was the spring semester of 2009, and I was alone in my dorm room, looking over notes for my film class on Spike Lee, trying to connect Malcolm X and Mo’ Better Blues in a way that felt entirely original. Blu & Exile’s Below the Heavens played as loudly as my second-generation MacBook would allow. I was a newly minted double major in English and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, nearing the end of my junior year. I lived in the W.E.B. Du Bois College House: a dormitory at the edge of Penn’s campus named for the philosopher, sociologist, novelist, and poet. Though Du Bois himself had a truly harrowing time as a faculty member at the university back in 1896—he was allowed neither to have an office nor to teach students during his time at Penn—the dormitory was as robust a reflection of human life on Earth as one might hope to see on a college campus: students from all over the world, mostly black and brown, choosing to live in this place for its emphasis on social justice, the arts, and the celebration of cultural practices from across the African diaspora.

It was in this uniquely boisterous environment—surrounded by the charismatic boasts of hip-hop and dance-hall, the steel boom of soca and kompa, hallways filled with laughter and conversation—that I looked up from my notes to see a missed call from a California area code. Whoever it was had left a voicemail message. I turned down the music and put my ear to the phone. The voice on the other side belonged to James Kass, founder and executive director of the nonprofit poetry organization Youth Speaks. Without much in the way of lead-up, and with a tone of palpable joy in his voice, James had asked if I would be interested in reciting one of my poems at the White House. I would have to agree to a thorough background check and be ready to go within the next week.

I can still remember looking at the phone, and then at the ceiling, and then at the desk across from my twin bed, covered with textbooks and printed notes. For a while I just sat there, frozen. I returned James’s call, and after what might have been the shortest round of small talk in my entire life (“Hi, James, it’s Josh—got your message. What’s going on now, exactly?”), we got to the matter of the voicemail. James told me that if I was interested, I would have the chance to recite my original work in the East Room, alongside various literary and dramatic luminaries. He had no other information to share at the time (which was fine with me, given how strong the opening pitch was) and instructed me to stay by the phone. In a few minutes, I received a call from Stan Lathan, who laid out all the details.

At this point, I had known Stan personally for a little over a year, though I was familiar with his work from a childhood spent watching it with family and friends. Over the course of his career, he had amassed directorial and production credits for Def Comedy Jam, Def Poetry, Sister Sister, and Martin along with numerous other black American televisual touchstones. In 2008, he produced an HBO documentary called Brave New Voices, which featured poetry slam teams from across the country as they were headed to an international youth slam competition by the same name. Back when I was a freshman at Penn, I’d earned a spot on the Philadelphia team that won the 2007 Brave New Voices title: a mélange of college students from Philadelphia-area schools and teenagers from around the city, with styles ranging from lyric poetry straight from the page to verses that called upon the cadence of the hip-hop styles that raised us. In 2008 we were set to return to BNV, hoping for a repeat performance. Weeks before the trip, we learned that the entire competition, as well as the road leading up to it, would be filmed by HBO. Our team was one of five that would be featured in a soon-to-be-televised documentary. For the better part of three months, the cameras followed us everywhere: across our respective campuses, and even to the neighborhoods we grew up in. They recorded our weekly practices, as well as our fundraising efforts on the streets of West Philadelphia: hours spent performing poems in shifts at the intersection of 40th and Walnut, right in front of the movie theater, my red New Era fitted cap left upside down on the sidewalk to collect cash donations from passersby.

After the Brave New Voices documentary aired, Stan helped create all sorts of other opportunities for me to share my work with the world. Three months before the White House event, he invited me to perform at the 2009 NAACP Image Awards in Los Angeles. Now he was inviting me to DC, only this time I would be the only one onstage. No friends or teammates—just me, and the microphone, and one of the hundred poems I had scrawled into various black-and-white notebooks over the years. According to Stan, for the event in question, An Evening of Poetry, Music, and the Spoken Word, I was to recite a new, original work—a two- minute poem, to be exact—on the theme of communication. The audience would include President Obama and the first lady, Michelle Obama. I thanked him for the opportunity and hung up the phone.

After the call, I ran laps around my dorm—and not my dorm room, to be clear, but the entirety of the Du Bois College House—for the next ten minutes. It took me a day or two, but I eventually settled on the poem I would read: “Tamara’s Opus,” an ode to my older sister. The subject of the poem was my relationship with Tamara, who is deaf, and by extension my relationship to American Sign Language, which I had struggled to learn as a child. Given the theme, and the stakes of the moment, I knew there was no other poem I could share from that stage. If I had an audience with the president, even if it was just for two minutes, this was the message I wanted to leave with him.

Excerpt from “Spoken Word: A Cultural History” by Joshua Bennett, copyright 2023 by Joshua Bennett. Published by Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Get the book here:

“Spoken Word: A Cultural History” by Joshua Bennett (Hardcover)

Buy locally from Indiebound

For more info: