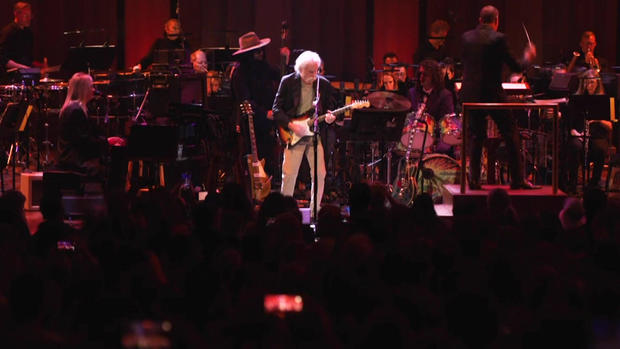

At Washington, D.C.’s Kennedy Center this past month, black tie met tie dye, as the National Symphony Orchestra and conductor Steven Reineke shared the spotlight with Grateful Dead co-founder Bob Weir and his band, Wolf Bros.

It’s a collaboration more than a decade in the making, where Grateful Dead classics (like “Shakedown Street,” “Dark Star,” and “Uncle John’s Band”) are reimagined as classical music.

CBS News

In preparation, Weir and his core band (Don Was, Jay Lane and Jeff Chimenti) spent weeks rehearsing in California.

Correspondent John Blackstone asked Weir, “Who’s going to be more intimidated going into this thing, the band or the symphony orchestra?”

“That’s an excellent question; I don’t know,” he replied. “I’m not sure that the orchestral players know what they’re walking into. Boy, this is going to be interesting!”

And so it was. For four nights the audience was on its feet, to the consternation of ushers unfamiliar with jam band etiquette. A triumph for orchestra and band … and for the music professor who brought culture and counterculture together.

CBS News

Giancarlo Aquilanti, an Italian composer at Stanford University, had never paid much attention to the Grateful Dead before meeting Weir in 2009. He’s now as dedicated to the music as any Deadhead.

“The music of the Grateful Dead, there’s so much material that somehow, once you get into it, when you get deeper into that understanding how they work – again musically, counterpoint, harmony, rhythm – I found that it translates into the orchestra in a very natural way,” Aquilanti said.

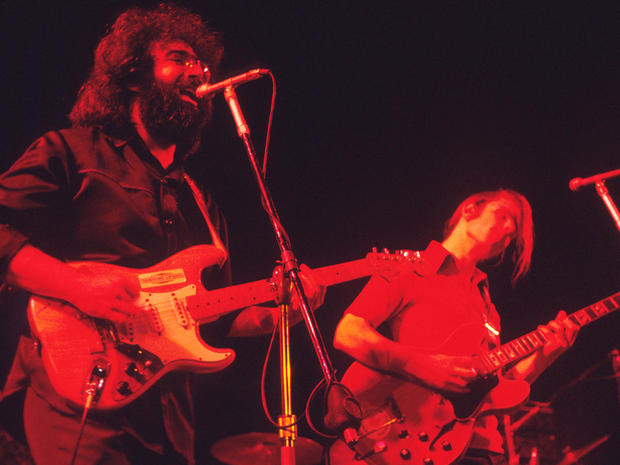

He studied the improvisation that was part of every Grateful Dead show, and he saw the influence of Weir’s longtime partner, Jerry Garcia.

Blackstone asked Weir, “In the Grateful Dead, he sang his songs, you sang your songs. You’re now singing his songs as well.”

“Yeah, I can’t sing them his way, and I’m not even gonna try. But yeah, those songs need to live. They need to live and breathe and grow.

“A song is a living critter,” Weir continued. “If I may wax hippie metaphysical for you, the characters in those songs are real. They live in some other world, and they come and visit us through the musicians, through the artists who have dedicated their lives to being that medium and inviting those critters from other worlds to come and visit our world and entertain the folks, because that’s all they want to do. It’s they just want to meet us and we meet them, and that’s what we do.”

CBS News

Jerry Garcia met Weir in 1963 in Palo Alto, California. Weir was 16, struggling in school but showing promise on the guitar. The Grateful Dead grew into a touring powerhouse, playing for an army of loyal fans, a trip that seemed to end when Garcia died in 1995 at the age of 53.

“Is any of this at all related to the fact that Jerry left so soon?” asked Blackstone.

“Well, he left some unfinished business,” said Weir. “We were partners. I’m going to do my best to tidy some stuff up for him. That’s what you do for your friends.”

Michael Putland/Getty Images

Aquilanti said, “I have some recordings of Jerry Garcia playing these guitars and it took me days, months sometimes to get one section to say, ‘This is it.’ So for me, it was like getting the soul of this man, [revisiting] him, and [giving] him an opportunity to be alive again into these orchestrations.”

Weir said, “Giancarlo has managed to put on a page what it was that we were reaching for, because we all always had this Philharmonic notion of what we were up to. That was always going on. I was thinking, ‘This is a horn line.’ And Jerry would hear it that way. But now, we can actually assign it to horns.”

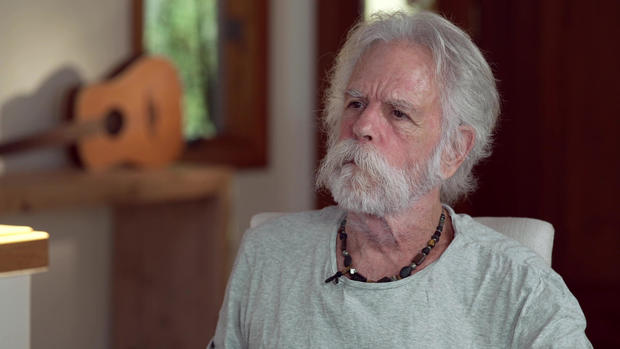

“I understand you don’t read music?” Blackstone asked Weir.

“Right.”

“You have to remember everything?”

“Yeah. You know, I’ve put some work into this. I have to, because I’m dyslexic in the extreme. I have to commit all this to memory.”

“Forgive me, but I can say this as a fellow man in his 70s, your memory may be fine, but it takes a little bit more time to recall sometimes.”

“So, I have to get it in my bones. It’s not a matter of memory so much as a matter of feeling it.”

Weir and his wife, Natasha, have two daughters, Monet and Chloe, both now in their 20s. To keep up with them, Weir is an avid fitness buff, something he shares on social media.

These workouts keep him road-ready for a concert schedule that includes next summer’s final tour with Dead & Company, a collaboration with guitarist John Mayer that’s been one of the top-grossing acts in the nation. Weir is also releasing live albums with Wolf Bros, and this coming February, they’ll join the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra for another three nights of truly classic rock.

For Bob Weir, it seems keeping the music of the Dead alive is nothing less than his life’s work.

Blackstone asked, “Is it one of your hopes from all this that the songs, your music, is going to live long after you’re not here?”

“My major consideration is, what are people going to say about what I’m doing in 300 years?” Weir replied. “A lot more doors are open to me now. And I’ll be stir fried if I’m just going to walk past that. If you’ve worked for your entire life to be able to work with a symphony orchestra on a meaningful level, how can you pass that up?”

WEB EXCLUSIVE: Watch an extended interview with Bob Weir by clicking on the video player below

For more info:

Story produced by Ed Forgotson. Editor: Ed Givnish.

See also: