CNN

—

Temple “Tempie” Cummins stoically stares at the camera with her arms folded in her lap, sitting stiffly in a chair in her dusty, barren backyard with her weather-beaten wooden shack behind her. Her dark, creased face reflects years of poverty and worry.

The faded black and white image of Cummins from 1937 was snapped by a historian who stopped by her home in Jasper, Texas, to ask her about her childhood during slavery. Cummins, who did not know her exact age, shared stories of uninterrupted woe until she recounted how she and her mother discovered that they had been freed.

She said her mother, a cook for their former slave owner’s family, liked to hide in the chimney corner to eavesdrop on dinner conversations. One day in 1865, she overheard her owner say that slavery had ended, but he wasn’t going to let his slaves know until they harvested “another crop or two.”

“When mother heard that she say she slip out the chimney corner and crack her heels together four times and shouts, ‘I’s free, I’s free,’ ” Cummins told the historian, who recorded her story for a New Deal writers’ project that collected the narratives of the formerly enslaved during the Great Depression. “Then she runs to the field, ‘gainst marster’s will and tol’ all the other slaves and they quit work.”

That story is one of the first recorded memoires of an experience that would inspire the creation of Juneteenth, an annual holiday celebrating the end of slavery that the US will commemorate this Monday. It marks the moment in June of 1865 when Union troops arrived in Texas to inform enslaved African Americans that they were free by executive decree. Many people like Cummins in remote areas of Texas and elsewhere did not know that they were free as their White owners hid the news from them.

Juneteenth has since become known as “America’s Second Independence Day.” Now a federal holiday, it will be celebrated by parades, proclamations, and ceremonies throughout the US. Though it commemorates a moment when enslaved African Americans were freed, the US is still held captive by several myths about slavery and people like Cummins.

One of the biggest myths that historians and storytellers have successfully challenged in recent years is that enslaved African Americans were docile, passive victims who had to wait until White abolitionists and “The Great Emancipator” Abraham Lincoln freed them. Black soldiers, for example, played a pivotal role in winning the Civil War. This new understanding of slavery has led to a rhetorical shift: It’s no longer proper to refer to people like Cummins as simply “slaves.”

“There’s been a shift in the historical community attempting to not define the period or the people by what was done to them in the sense that their identity becomes a noun, a slave, but rather that they are that they were in the process of being enslaved,” says Tobin Miller Shearer, a historian and director of African American Studies at the University of Montana.

“There were slavers who did that to them,” he says, “but there’s more to their identity than what was being done to them.”

Yet other myths about slavery persist, in part, because of the sheer enormity and brutality of slavery.

“The enslavement of an estimated ten million Africans over a period of almost four centuries in the Atlantic slave trade was a tragedy of such scope that it is difficult to imagine, much less comprehend,” Albert J. Raboteau wrote in “Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South.”

Here are three other myths about slavery that historians say persist:

There is a popular conception that the formerly enslaved were freed after the Civil War ended. But many had to continually fight for their freedom because so many Whites still tried to keep them in captivity and were willing to use deceit and violence to do so.

The author Clint Smith described this dynamic in his New York Times bestselling book, “How the Word is Passed: A Reckoning with The History of Slavery Across America.” Smith said the Juneteenth jubilation didn’t last for many formerly enslaved people. Former Confederate soldiers still tried to round up Black “runaways” to return them to their owners though that term no longer had any legal merit. And White vigilantes tracked down and punished formerly enslaved people.

Smith unearthed the narrative of a woman named Susan Merritt of Rusk Country, Texas, who recounted what happened when some people like Cummins in Texas tried to claim their freedom:

“Lots of Negroes were killed after freedom…bushwhacked, shot down while they were trying to get away,” Merritt said. “You could see lots of Negroes hanging from trees in Sabine bottom right after freedom. They would catch them swimming across Sabine River and shoot them.”

And then there was the practice of taking away Black freedom through other means, like convict-leasing programs and a corrupt justice system throughout the South that the historian Douglas A. Blackmon documented in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Slavery By Another Name.”

The lesson from history: Slavery didn’t end with the Emancipation Proclamation. Black people still had to literally fight for their freedom long afterward. Smith quotes the historian W. Caleb McDaniel who wrote:

“Slavery did not end cleanly or on a single day. It ended through a violent, uneven process.”

Mention slavery and it still evokes images of half-naked Africans stumbling onto the American shores, struggling to learn to read and write in a strange and alien land. The focus of many stories about the formerly enslaved is what was taken from them. But they gave plenty to America in ways that are still not appreciated.

Captive Africans who came here didn’t need to be civilized. They came to the US as fully formed individuals, not blank canvases, with their own cultures and specialized knowledge, says Leslie Wilson, a historian at Montclair State University in New Jersey.

The thumbprints of the culture that formerly enslaved people created are now stamped on virtually every facet of American culture, Wilson says. By the Civil War, Black people had already changed American concepts of architecture, burial, music, storytelling and medicine, Wilson says.

“Much of Southern culture is nothing more than blackness,” Wilson says. “It is the blues and jazz of the 19th century and the rock and roll of the 20th. It is the chicken and grits, the way that people rock in church or the cadence of the pastor.”

If that sounds like hyperbole, consider how much of Americans’ contemporary landscape is shaped by the legacy of the formerly enslaved:

- The Statue of Liberty was originally created to commemorate freed enslaved people, not the arrival of immigrants.

- An enslaved person called Onesimus changed the way Americans treated epidemics, pioneering a technique to prevent the spread of smallpox that he had learned from his native West Africa.

- Country music owes much of its musical legacy to the influence of the formerly enslaved. The banjo, for example, is a descendant of an instrument that was brought to America by enslaved West Africans and many of the genre’s earliest hits were adapted from slave spirituals.

- Bugs Bunny cartoons and other stories like Brer Rabbit featuring clever, talking animals were originally inspired by African folktales first told by enslaved people.

Black and White culture is so intertwined that the cultural critic, Albert Murray, declared in his book, “The Omni-Americans,” that “American culture is “incontestably mulatto.” White and Black people in the US “resemble nobody else in the world so much as they resemble each other.”

“The United States is in actuality not a nation of black people and white people. It is a nation of multicolored people,” Murray wrote. “Any fool can see that the white people are not really white, and that black people are not black. They are all interrelated one way or another.”

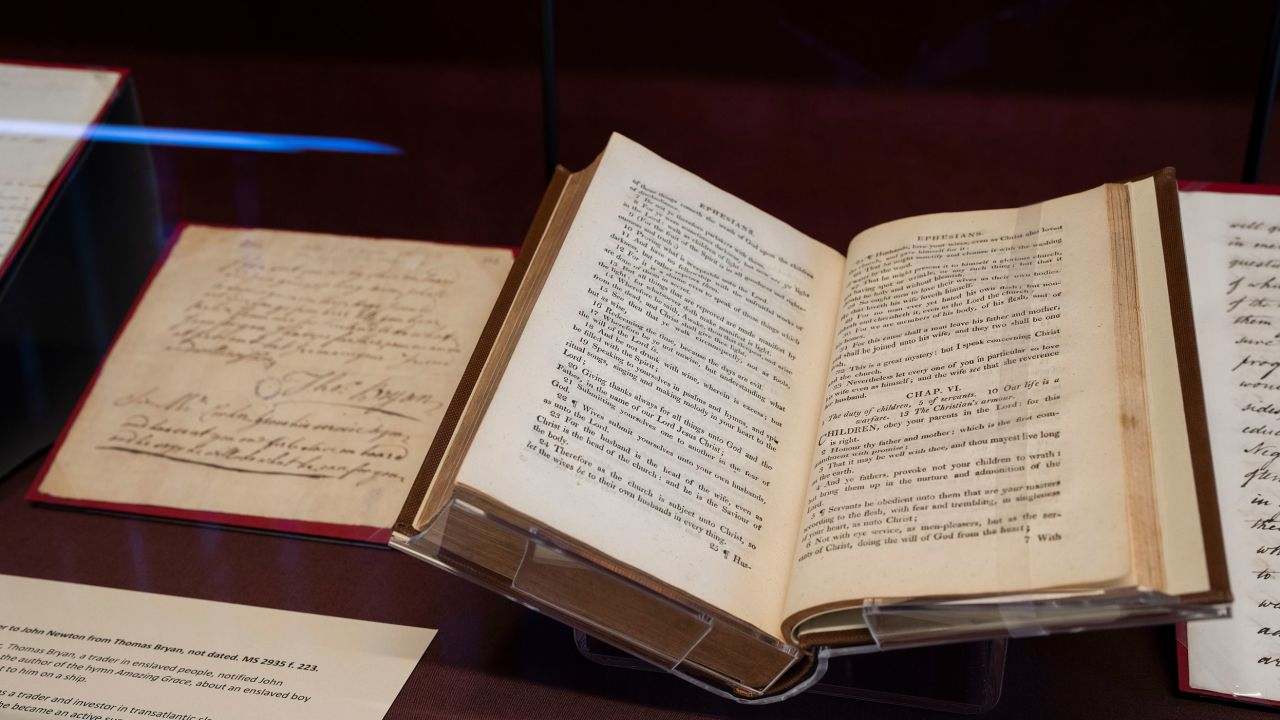

In the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, there is a special exhibit of an artifact that is so rare that there are only a handful now in existence. It is what historians call a “Slave Bible.” It is a copy of a Bible that was used by British missionaries to convert enslaved African Americans. Published in 1807, the Bible deletes any passages that may inspire liberation – about 90% of the Old Testament is missing along with half of the New Testament.

“They literally blacked out, portions of the Bible that had anything to do with freedom, anything to do with equality, anything to do with God delivering folk,” says Leon Harris, a theology professor at Biola University in California.

There is misconception that Christianity was successfully used to create docile slaves who were conditioned to heed New Testament passages such as “slaves obey your earthly masters.” Malcolm X derided Christianity as a White man’s religion used to brainwash Black people to “shout and sing and pray until we die ‘for some dreamy heaven-in-the-hereafter’” while the White man “has his milk and honey in the streets paved with golden dollars right here on this earth!”

But historians like Harris say most slaves disdained the type of Christianity that was taught to them. Many instead discovered those missing passages in the Slave Bible, such as the Old Testament stories of God freeing the Israelites from Egyptian captivity. It’s no accident that many Black leaders who have led freedom struggles, from Nat Turner to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., were Christian ministers.

“Instead of Christianity being a religion of African oppression, many interpreted it as a religion of freedom,” Harris says.

The historical record shows that enslaved African Americans revitalized Christianity in other ways, historians say. They injected emotionalism and an emphasis on ecstatic worship into evangelical Christianity that can still be seen in how many White Pentecostal worship today. And Negro spirituals, often called the nation’s first musical form unique to America, continue to be sung throughout churches of all races and ethnicities today.

Former slaves remade Christianity – it didn’t remake them, says Raboteau, author of “Slave Religion.” He wrote that it had a “this-worldly” impact:

“To describe slave religion as merely otherworldly is inaccurate, for the slaves believed that God had acted, was acting, and would continue to act within human history and within their own particular history as a peculiar people just as long ago he had acted on behalf of another chosen people, biblical Israel,” Raboteau wrote.

This year, Juneteenth comes at a time when White educators and politicians are passing laws that ban the teaching of Black history in schools that could make White students or others feel “discomfort.” How many students will be able to learn about the resilience of the formerly enslaved?

That’s a question that no holiday celebration can answer. But one historical debate has been settled:

Even as the stories of the formerly enslaved are forgotten by history, we live in a contemporary America that was profoundly shaped by how they resisted captivity – whether some of us care to know it or not.

John Blake is a Senior Writer at CNN and the author of “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.”