NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

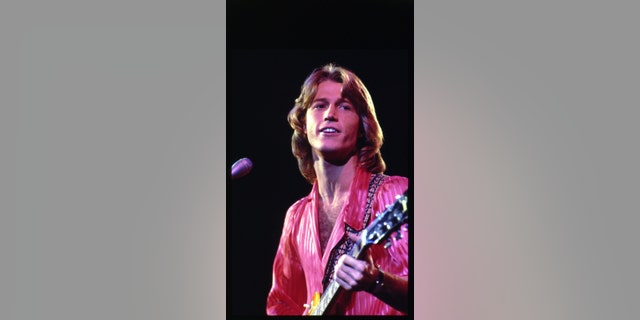

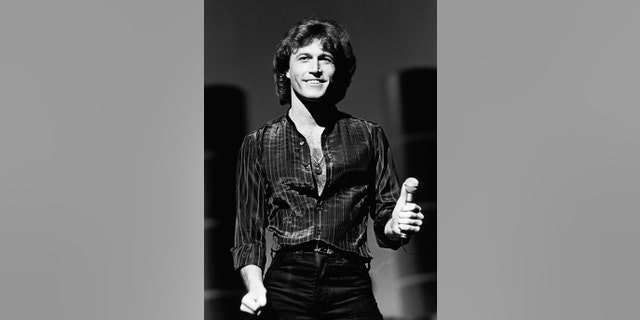

Andy Gibb, the pop singer who skyrocketed to fame as a teen idol, was hopeful to make a comeback before his life came to a sudden end at age 30.

In 1987, the disco sensation, who once had six hit records in the late ‘70s, declared bankruptcy and was reporting an annual income of less than $8,000. Still determined, the younger brother of the Bee Gees was planning his return to music. Barry Gibb even took his younger sibling to London where they could collaborate once more. In early 1988, Andy moved to a carriage house on the property of his brother Robin Gibb. He had signed a contract with Island Records. His future looked brighter.

“At that point, Andy seemed happy and healthy,” author Matthew Hild told Fox News Digital. “He finally signed a record contract in London. He was going to work on an album. Things were finally looking up. He was outgoing and enthusiastic. But he was also living alone. And Andy didn’t like being alone in his life – ever. When it was time to get back to work, his confidence began getting shaky. He lost faith and his ability to make a comeback. But he was eager to make what should have been his next album… His last days were a combination of hopefulness, but also depression and insecurity.”

Andy Gibb is the subject of a new biography written by Matthew Hild titled ‘Arrow Through the Heart’.

(Photo by Fin Costello/Redferns)

According to Hild, Andy was hospitalized three times, complaining of chest and abdominal pains. On the evening of March 9, 1988, Andy collapsed on Robin’s estate. He died the next morning of myocarditis, known as inflammation of the heart muscle.

‘PUNKY BREWSTER’ STAR SOLEIL MOON FRYE REVEALS FIRST CRUSH: ‘I LOVED HIM SO MUCH’

Andy’s story is chronicled in Hild’s new book titled “Arrow Through the Heart,” which has been optioned by Lisa Saltzman’s Groundbreaking Productions. It explores how Andy branched out on his own as a sought-after star and how his struggles with addiction contributed to his tragic end.

A spokesperson for Barry, the only surviving member of the Bee Gees, did not immediately respond to Fox News Digital’s request for comment concerning Hild’s book.

Andy Gibb’s hit songs include ‘I Just Want To Be Your Everything’ ‘Shadow Dancing’, ‘An Everlasting Love’ and (Our Love) Don’t Throw It All Away’.

(Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

“In 2020, Barry’s documentary ‘How Can You Mend a Broken Heart’ had come out,” Hild explained. “Andy was mentioned of course, but I felt no one had taken the time to really tell his story. His life was a short one, but he achieved so much while he was here. We all know how he died, but how did he really live? That’s the story I wanted to tell.”

Hild said he obtained access to never-before-heard interviews from over the years. And while several sources were hesitant at first, many who knew and worked with Andy came forward to share their accounts. Hild said that while Barry, 75, declined to participate, he is aware of the book’s release.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT NEWSLETTER

“Sadly, Andy Gibb is remembered by many for his problems,” said Hild. “Some may assume he only made it because of his brothers. But that’s just not true. He had incredible talent on his own. At a very young age, he did his own songwriting. At ages 16 and 17, he was writing a lot of great songs that ended up on the very first album. He knew how to command an audience on stage as a performer. He had the looks, but the talent really spoke for itself. And I was especially touched at how many people, even today, are so protective of Andy and his memories. He was a star, but he was also kind, generous and had a sweet nature about him.”

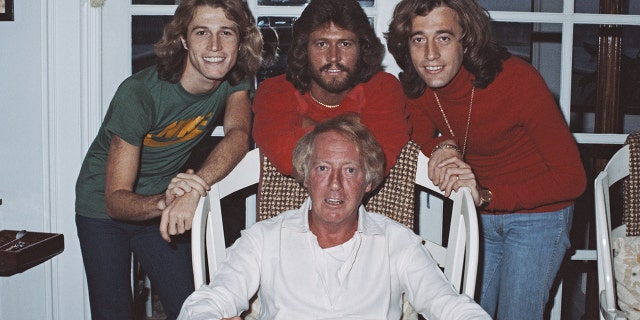

From left: singers Andy Gibb (1958 – 1988), Barry Gibb, and Robin Gibb (1949 – 2012) with Australian music entrepreneur Robert Stigwood (1934 – 2016), February 1979.

(Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images)

The English-Australian singer was still a child when his brothers had their first big hit as the Bees Gees, a sibling singing group. It was Barry who encouraged his younger brother to pursue his interests in music and even gifted him his first guitar. As a teen, Andy pursued music and started his group called Melody Fayre in the mid-‘70s. The band split up while they were in Australia and Andy soon had another band called Zenta. Andy caught the eye of Robert Stigwood, the Bee Gees manager and film producer.

In 1976, Andy, who was just 18, headed to Miami, Florida and began working on his first album, 1977’s “Flowing Rivers,” alongside Barry. With his boyish good lucks and captivating vocals, Andy launched a wildly successful solo career. His next album, 1978’s “Shadow Dancing,” went multi-platinum.

Andy’s hit songs include ″I Just Want To Be Your Everything,″ in 1977, ″Shadow Dancing″ and ″An Everlasting Love″ in 1978 and ″(Our Love) Don’t Throw It All Away″ in 1979.

Andy Gibb, who was faced with insecurity and depression as his fame grew, struggled with cocaine addiction.

(Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images)

“Andy was getting checks that would have been $4 million today and women were chasing him everywhere,” said Hild. “His father said he was given too much too soon and that overwhelmed him. He went from playing in little nightclubs in Australia to having number one hits in the United States and being everywhere – in magazines, on the radio, on television. But he was quietly struggling with imposter syndrome. Even though he had this undeniable talent, he wasn’t fair to himself. And he was in the shadow of his brothers who were also incredibly successful. I think a large part of him felt that he was only successful because of his brothers.”

“There are a lot of people today, still puzzled years later, about what drove Andy to his demons,” Hild continued. “You have to remember this was someone who, at 19, became a superstar overnight. He felt like he could handle it all… Even though he had everything somebody could possibly want – the money, the fame, the fans – he was empty inside. Betty White’s agent even told me that he would tell Andy, ‘Look in the mirror. Women love you. Men want to be you. You’ve got the talent.’ But he also said, ‘I always had the feeling that when Andy looked in the mirror, he just saw nothing.’”

According to Hild, Barry would even tell Andy, “We have three of us [as the Bee Gees], but look at what you do. We can’t do that.”

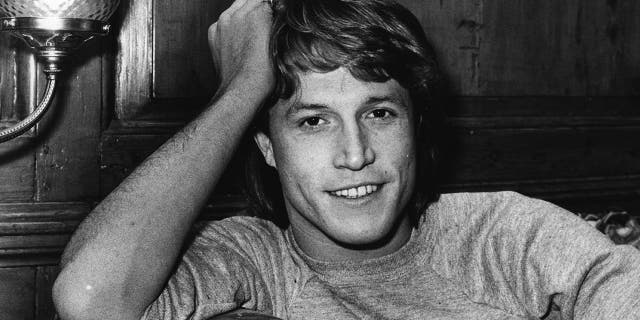

Andy Gibb was the younger brother of Robin, Maurice and Barry who make up the Bee Gees. He made it on his own as a solo artist, but those who knew Gibb said fame came too fast.

(Photo by Robin Platzer/Getty Images)

But Andy, who idolized his eldest brother, felt uncertain about his talents despite receiving constant assurance from him. Hild said Barry adored his brother and believed in his talent.

Hild claimed that privately, Andy struggled with his insecurities as he attempted to cope with fame. Then temptation in Miami Beach came calling.

“Cocaine was rampant,” said Hild. “I think it started very innocently since it was part of the culture. Many artists during this era were using cocaine.”

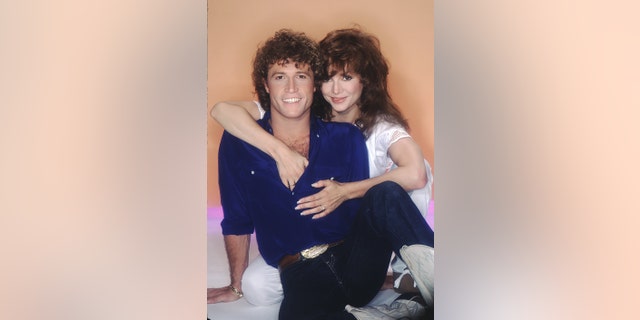

Andy Gibb and then-girlfriend, actress Victoria Principal, pose for a portrait in 1981 in Los Angeles, California.

(Photo by Harry Langdon/Getty Images)

Andy also struggled in his personal life. According to Hild, he fell head over heels for “Dallas” actress Victoria Principal in 1981. But the whirlwind romance was also tumultuous. According to reports, drugs were a contributing factor to their split.

“The relationship was pretty stormy by all accounts,” said Hild. “[But] Andy’s problems started long before Victoria… and when they broke up, he was just devastated. Andy’s role models were his brothers, especially Barry. All the brothers found love early and had these lengthy marriages. His parents also had a very long marriage. Some people told me that Andy wanted the kind of relationship that his brothers and parents had. He had a brief marriage to Kim Reeder [from 1976 to 1978] and they had a daughter. But he never found that lasting relationship he was looking for. He wanted a long, lasting marriage, a happy family, a peaceful home life and a bunch of children. It just never happened.”

Andy’s struggles with drugs worsened, and it became known in the industry, the author pointed out. In 1982, Andy admitted to “Good Morning America” that he had “a very bad nervous breakdown.”

Those who knew Andy Gibb, including Olivia Newton-John, were protective of the late star’s legacy and memory, said author Matthew Hild.

(Photo by GAB Archive/Redferns)

“I had everything I wanted, and I just blew it all up,” Gibb admitted at the time.

Andy’s family urged him to go to rehab, and he finally did in 1985 when he checked into the Betty Ford Center. But once a clean Andy was out, he could not relaunch his once thriving career.

“By the time he was ready to work again, his reputation was just shot,” said Hild. “He had a reputation for being unreliable. He had opportunities to do films and television shows, but too many times, he wouldn’t show up for things. And he was away from pop music for a long time. The industry had changed. People who would have hired him for things were now afraid to touch him… But he still talked of his comeback. He was trying even at the end.”

Andy Gibb was gearing up to work on his comeback album when he passed away in 1988 at age 30.

(Photo by Stuart Nicol/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Andy passed away five days after his birthday. A pathologist found no evidence of alcohol or other substances. The inflammation of his heart was the result of a viral infection.

His mother Barbara Gibb once said, “When he died, it had nothing to do with drugs at all, but the damage had been done through drugs in the first place.”

Hild said that Andy’s heart problem was “going on for years and was likely drug-related.”

Andy Gibb had one daughter with Kim Reeder.

(Photo by PL Gould/IMAGES/Getty Images)

“I think what ultimately destroyed Andy was his insecurities,” said Hild. “Several people told me they believed his addictions came from his emotional struggles dealing with fame so quickly. And when he couldn’t hold on to that career, he became depressed. And that overwhelmed him.”

Hild hopes that his book will encourage readers to reassess Andy’s legacy in music.

“His problems were so heavily publicized, and it sadly overshadowed his work,” said Hild. “But he was so much more than the kid brother of the Bee Gees. He had the courage to pursue music on his own. His career was a triumph. Who knows what he could have further accomplished had he lived? He had it all, but he lost his way.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.