CNN

—

The first time the Supreme Court upheld the use of affirmative action in college admissions, nearly 45 years ago, the justices spent months strategizing, forming back-channel alliances and trading passionate pleas up until the final days of negotiations.

Then, just days before the June 1978 decision was released, one justice wrote in a private account, “all hell broke loose.”

That hard-fought precedent in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke is the touchstone for two cases to be argued next week on admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. Today’s reconstituted conservative court appears on the cusp of reversing the landmark that has let colleges consider students’ race in admissions, expanding opportunities for Blacks, Hispanics and other minorities for more than four decades.

Private papers of deceased justices, including the first Black justice, Thurgood Marshall, reveal the tactics among the nine that produced the 1978 decision and how competing factions tried to steer the outcome.

The eventual judgment fell to a moderate, centrist justice, Lewis Powell, whose role points up a striking difference between that court and the modern bench: There is no middle. Unlike in past decades, the current court has shunned compromise and plowed through precedents, as demonstrated by June’s decision overturning the 1973 Roe v. Wade abortion rights landmark.

The late Powell was succeeded in the centrist role over the years by such middle-ground brokers as Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy, both of whom are now retired and have no counterpart on today’s polarized bench dominated by six conservatives with only three liberals.

Based on previous sentiment from justices in today’s right-wing majority, the court appears ready to overturn Bakke and upend practices designed to boost campus diversity.

Yet there are some similarities between then and now, notably the profound national attention to the issue.

Back in 1978, Justice William Brennan, who served from 1956 to 1990, wrote in his personal history of the Bakke negotiations, “This case aroused more interest in the Nation, the press, and the Bar than any I have seen in my 22 terms on the Court.”

He added that: “the level of activity behind the scenes on the Court reflected and was perhaps commensurate with the intense public interest.”

Brennan’s case history was opened relatively recently in his Library of Congress archive, only after the 2019 death of John Paul Stevens, the last surviving member of the court that decided Bakke.

Brennan began laying groundwork for a decision that he hoped would forcefully allow the use of race in admissions to remedy past discrimination even before oral arguments were held in October 1977.

But he wasn’t the only one. As Brennan wrote, he discovered “that several of my Brethren were already deeply immersed in Bakke and that at least one was already involved in preliminary maneuvering.”

The justices anticipated the difficulty of the case, and many circulated early memos staking out positions. Yet, unlike in most cases, assignment of the opinion for the majority was delayed for months after the October oral argument, and the vote of one final justice was not cast until the following May. The decision was announced on June 28, 1978.

Still, for all the internal wrangling among the justices, the decisive opinion adhered closely to a 30-page, November 22, 1977, memo Powell wrote to his colleagues laying out a rationale that would permit racial affirmative action to attain a diverse student body.

“This clearly is a constitutionally permissible goal for an institution of higher education,” Powell wrote as he drafted that memo. “Academic freedom, though not a constitutional right in itself, long has been viewed as a special concern of the First Amendment.”

No single opinion drew the requisite five votes for a majority, and Powell’s opinion, bridging the dueling positions on the right and left, eventually stood for the court’s judgment.

The phrase “affirmative action” traces to the late President John F. Kennedy, who issued a 1961 executive order requiring government contractors to take steps, “affirmative action,” to ensure they did not discriminate on the basis of race, creed, color, or national origin. President Lyndon B. Johnson then signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting race discrimination and leading to a sea of change in the workplace and in higher education.

The Bakke case was one of the first at the Supreme Court testing whether programs designed to help Blacks were unlawfully disadvantaging Whites. The case was initiated by Allan Bakke, a White applicant who was twice rejected from the University of California at Davis medical school, which used a screening system that reserved 16 out of 100 seats for Blacks, Hispanics, and other minority applicants. Bakke won in California Supreme Court, and the regents of the University of California appealed.

The question then and today in the North Carolina and Harvard cases is whether race-based affirmative action violates the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection of the law or Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, covering private schools that receive federal funds.

In 1978, the nine justices ended up issuing six individual opinions, the most crucial being Powell’s, which endorsed the use of race in admissions (along with various academic and extracurricular criteria) based on universities’ interest in student body diversity but rejected a justification tied to past discrimination and any use of numerical quotas.

Powell’s view was cemented by alternating support from four justices on his left (who would have justified race on broader grounds and allowed quotas) and four justices on his right (who believed the UC-Davis program violated Title VI and wanted to hold off on whether race could ever be a factor in admissions).

The Bakke drama may foreshadow the current dissension behind the scenes on a bench with only three remaining liberals, one of whom is the nation’s first Black woman justice, Ketanji Brown Jackson. (Jackson will hear arguments in the North Carolina case, but has recused herself from the Harvard dispute, having previously served on Harvard’s board of overseers.)

Brennan and Marshall had actually opposed the court’s decision to take up the California university appeal, fearing a nationwide ruling against affirmative action.

After they were outvoted, Brennan said Marshall “suggested that we find some pretext to get rid of the case because he firmly believed that quotas were often indispensable to affirmative action programs.”

Referring to a 1974 affirmative action case (DeFunis v. Odegaard) that had been declared moot, Brennan said he told Marshall he “simply could not be party to any such action” again dismissing the case. Brennan added that he would “prefer losing on the merits to seeing the Court once again avoid any decision of this issue” once it had been accepted for oral arguments. Brennan also was not as pessimistic as Marshall about how the Bakke case would play out.

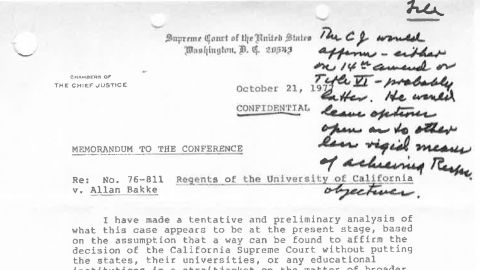

Those two liberals were keeping their eye on the conservative justices, particularly Chief Justice Warren Burger, a 1969 appointee of President Richard Nixon. The chief justice sent around one of the first memos in the case, on October 21, 1977, proposing to affirm the California Supreme Court decision favoring Bakke. Burger sought a decision focused on the Davis program, with its explicit quota system, rather than grapple with broader admissions programs that used race as one factor with other criteria and avoided quotas.

He drew back from the broader question, bristling at all the public concern.

“With all deference to the distinguished array of counsel who have been plunged into a very difficult case on a record any good lawyer would shun, I see no reason why we should let them (aided by the mildly hysterical media) rush us to judgment,” Burger wrote.

“The notion of putting this sensitive, difficult question to rest in one ‘hard’ case is about as sound (as) trying to put all First Amendment issues to rest in one case,” he wrote. “…If it is to take years to work out a rational solution of the current problem, so be it. That is what we are paid for.”

Burger, joined by then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist and Justices Potter Stewart and Stevens, began working on an opinion that would invalidate the UC-Davis program under Title VI’s prohibition on race discrimination. Stevens wrote the final opinion for this wing.

Brennan, Marshall and Justice Byron White believed the use of race in admissions was valid under the statute and the Constitution. In a November 23 memo, Brennan observed that past cases had held that “not every remedial use of race is constitutionally forbidden.”

He added in a practical vein that “it is undisputed that prior to the adoption of race-sensitive programs, the numbers in which minorities were admitted to medical schools were so niggling as to severely embarrass the nation’s determination that minorities should fully participate at all levels of society.”

Both factions tried to persuade Powell in their respective directions, but he held fast to his limited rationale and prominently used as a model Harvard’s admissions practices that consider race as a “plus” factor with other criteria and set no quotas. (It is now, in fact, the Harvard program the justices are scrutinizing, along with University of North Carolina admissions practices.)

Brennan wrote in his personal account that Powell was “immoveable,” repeatedly spurning arguments that affirmative action was justified by enduring racial discrimination and underrepresentation in professional schools.

Through those negotiations, it was unclear where Justice Harry A. Blackmun, a 1970 appointee of Nixon and the author of the 1973 Roe v. Wade, would land. He was recovering from prostate cancer surgery and continued to postpone his vote in the case.

That caused suspense, and particular concern on the left: for a decision upholding some form of affirmative action, Blackmun’s vote was needed – with Powell, at a minimum, or with the Brennan trio, rather than the foursome of Burger, Rehnquist, Stewart and Stevens.

Brennan, the senior justice on the left, was legendary for his strategic sense and ability to cajole a fifth vote. As he considered ways to approach Blackmun, he was simultaneously worried about irritating him.

“HAB’s clerks told mine that HAB became quite irritable when the subject of Bakke was raised,” Brennan wrote, referring to Blackmun by his initials. “One of my clerks suggested that I approach HAB on the subject, but I knew that would be the wrong tactic. He is so sensitive and independent that an overture from me was more likely to lose his vote than to move the case forward.”

Brennan recounted that in early 1978 he gave Blackmun a desired opinion assignment shortly before the justices were scheduled to hold another private session on the Bakke case.

The chief justice, when he is in the majority, has the power to decide who will write the opinion for the court. When the chief is in dissent, the senior justice in the majority has the assignment power. That authority to make assignments is often used for leverage, most obviously to ensure certain limits on the ruling to keep the requisite five votes on board. It can also be used to favor a colleague, particularly when that justice has indicated he or she wants the assignment.

“During the week prior to the special conference,” Brennan wrote in his case history, referring to a session the justices had scheduled to again discuss Bakke, “I found myself in a position to assign the court opinion in Franks v. Delaware, in which the justices had voted to overrule the longstanding rule that a court cannot look beyond the four corners’ of a search warrant in determining whether a search satisfied the Fourth Amendment.”

“HAB approached me immediately after Conference and told me that his health would not preclude his working effectively on a major case like Franks, clearly asking me for the assignment. His request caused me great difficulty. Thus far this term, HAB had, in my view, mishandled the court opinions in (two other cases), and I feared than an opinion by HAB in Franks could undercut a significant victory. But, on the other hand, I recognized that, if I irritated him on the eve of the Bakke conference, I risked losing his vote. So in the end I relented, to the consternation of my clerks. HAB, however, was delighted.”

As Blackmun took up that assignment, he was still weeks from committing in the Bakke case.

One of the most impassioned memos in the justices’ Bakke archives was written on April 13, 1978, by Marshall, appointed to the bench in 1967 by Johnson as the first Black justice. He was frustrated by Powell’s position and Blackmun’s apparent wavering.

“I repeat, for next to the last time: the decision in this case depends on whether you consider the action of the Regents as admitting certain students or as excluding certain other students,” Marshall wrote.

He referred in this memo, made available at the Library of Congress in 1993, to the admission of “qualified students who, because of this Nation’s sorry history of racial discrimination, have academic records that prevent them from effectively competing for medical school” and described affirmative action as a way “to remove the vestiges of slavery and state imposed segregation by ‘root and branch.’”

(The court in 1968 had ruled that school officials must affirmatively try to eliminate segregation “root and branch” from public schools; the decision came more than a decade after the 1954 landmark Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine, through the efforts of Marshall when he was a prominent civil rights attorney.)

Marshall pointedly addressed the consequences for Blacks, even within the court’s own walls.

“I wish also to address the question of whether Negroes have ‘arrived,’” Marshall wrote. “Just a few examples illustrate that Negroes most certainly have not. In our own Court, we have had only three Negro law clerks, and not so far have we had any Negro Officer of the Court. On a broader scale, this week’s U.S. News and World Report has a story about ‘Who Runs America.’ They list some 83 persons – not one Negro, even as a would-be runnerup.”

Brennan was a personal friend of Marshall and understood his fervor on race. But he plainly was also keeping his eye on the vote count.

Brennan wrote in his case history of the Marshall memo, “My initial reaction to it was that it was likely to help our cause since it was an eloquent statement of outrage at the treatment of Blacks. However, upon further reflection, it occurred to me that the memo might do more harm than good, for it seemed to assume that the constitutional standard should really be color blindness. … TM’s underlying theory was ‘Goddamit, you owe us,’ and I wasn’t sure that would be persuasive to HAB.”

Blackmun did not reveal his ultimate decision until May, but when he did, he voted robustly to uphold the use of racial affirmative action, joining with Brennan, Marshall and White, a 1962 appointee of Kennedy.

That meant a 4-1-4 vote, and to Brennan “a partial victory for the view I had championed,” along, of course, with Marshall and White.

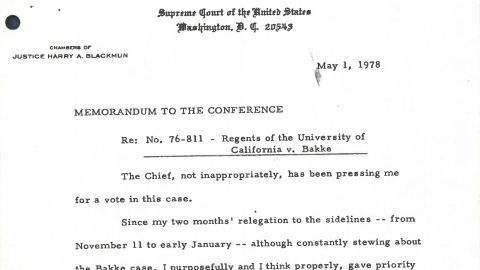

When Blackmun sent a memo to his colleagues on May 1, he acknowledged that he had tested their patience.

“The Chief, not inappropriately, has been pressing me for a vote in this case,” he wrote. “Since my two months’ relegation to the sidelines – from November 11 to early January – although constantly stewing about the Bakke case, I purposefully and I think properly, gave priority to the attempt to stay even with all the other work. I feel that I have been successful in this and that, except for Bakke, and I have held nothing up for a dissent or for other reason.”

As he concluded his 13-page memo, Blackmun wrote, “For me, this case is of such importance that I refused to be drawn to a precipitate conclusion. I wanted the time to think about it and to study the pertinent material. Because weeks are still available before the end of the term (in June), I do not apologize; I merely explain.”

Demonstrating his dedication to race-based remedies, Blackmun began writing a separate opinion emphasizing that affirmative action conformed to the “original intended purposes” of the Fourteenth Amendment related to “complete equality.”

To Burger on the right and Brennan on the left, it was now clear that Powell would express the judgment of the court. As Powell continued refining his own arguments and took note of the views of the dueling camps, there were more bumps among those on Powell’s left. Brennan sent around a near-final draft of his separate opinion on the evening of Friday, June 23, to White, Marshall and Blackmun.

“On Saturday, all hell broke loose,” Brennan recounted, writing of White and Blackmun. “First, BRW called me at home to say he could not live with the changes relating to the standard of review.”

The 11th hour disagreement came down to the wording used to describe the scrutiny judges were to give state programs tied to race, and Brennan acted quickly. “I went to the office to discuss this with BRW. On arriving there, my clerks told me HAB had called. I called HAB and he, too, indicated he was pulling out of the opinion. HAB was simply very mad that we had made a lot of changes.”

Tempers tend to fray in late June, as the justices are up against deadlines, yet, as often happens, differences get resolved, as occurred with the joint Brennan, White, Marshall and Blackmun opinion.

The enduring opinion was Powell’s, through the power of his fifth vote straddling the two sides.

On one hand, he wrote, aligning with the four to his right, “the purpose of helping certain groups whom the faculty of the Davis Medical School perceived as victims of ‘societal discrimination’ does not justify a classification that imposes disadvantages upon persons like (Bakke), who bear no responsibility for whatever harm the beneficiaries of the special admissions program are thought to have suffered.”

But then Powell, in league with the four on his left, said a separate goal of the school – the attainment of a diverse student body – was constitutionally permissible for an institution of higher education.

“Academic freedom, though not a specifically enumerated constitutional right, long has been viewed as a special concern of the First Amendment,” Powell wrote in his final opinion. “The freedom of a university to make its own judgments as to education includes the selection of its student body.”

Powell would hear from colleagues on lower courts praising his middle-ground approach, including Judge Henry Friendly, then on a federal appellate court in New York and soon to hire a young John Roberts as a law clerk. In a note dated July 1, 1978, Friendly wrote, “I must write to express my appreciation for the great service you have rendered the nation. This case had the potential of being another Dred Scott case.”

Before all was said and done, though, and people responded, Powell had to figure out how to present his solo opinion from the bench. In one memo to the other eight, he described himself as “a ‘chief’ with no ‘indians,’” and protested that “I should be in the rear rank, not up front.”

As he circulated a copy of the statement he proposed to read from the bench, he told his colleagues, “My primary purpose was to assist the representatives of the media present in understanding ‘what in the world’ the Court has done!”

Twenty-five years later, in 2003, the Supreme Court reaffirmed Powell’s reasoning in a case from the University of Michigan and said judges should defer to a university’s judgment that “diversity is essential to its educational mission.”

Writing for the majority in Grutter v. Bollinger, Justice O’Connor observed, “It has been 25 years since Justice Powell first approved the use of race to further an interest in student body diversity in the context of public higher education. Since that time, the number of minority applicants with high grades and test scores has indeed increased. We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”

When the justices rule on the Harvard and North Carolina cases, likely next June, it will be 20 years since O’Connor penned those memorable words grounded in Powell’s seminal opinion.