Lety, Czech Republic

CNN

—

Čeněk Růžička looked euphoric as he swung the pickaxe against the wall. He had spent decades campaigning for the pig farm to be torn down. It was finally happening.

The piggery, a giant industrial operation, stood on the remnants of the Nazi-era Roma concentration camp where some of his ancestors died.

It lay near Lety, about 80 kilometers (50 miles) south of Prague, and was built in the early 1970s after the Communist regime rejected a proposal to build a Romani Holocaust memorial there.

It took 50 years for the country to recognize the farm was a disgrace to the memory of those held in the camp and to flatten it. The demolition started last summer and is now nearly finished – with a memorial to be opened on the site next year. But to many Roma people, the saga remains a symbol of the racism, discrimination and prejudice they still face on daily basis.

They believe the farm was allowed to be built because the prisoners were Roma, a group that remains the most marginalized community in the Czech Republic.

“It’s hard to wrap your head around it,” said Jana Kokyová, Růžička’s niece and the head of the Czech Committee for the Redress of the Romani Holocaust. “Hundreds of people were tortured there, they were murdered there and then the communist government builds a pig farm there with 13,000 pigs defecating on top of these people’s remains. It’s horrendous,” she told CNN in an interview in Prague.

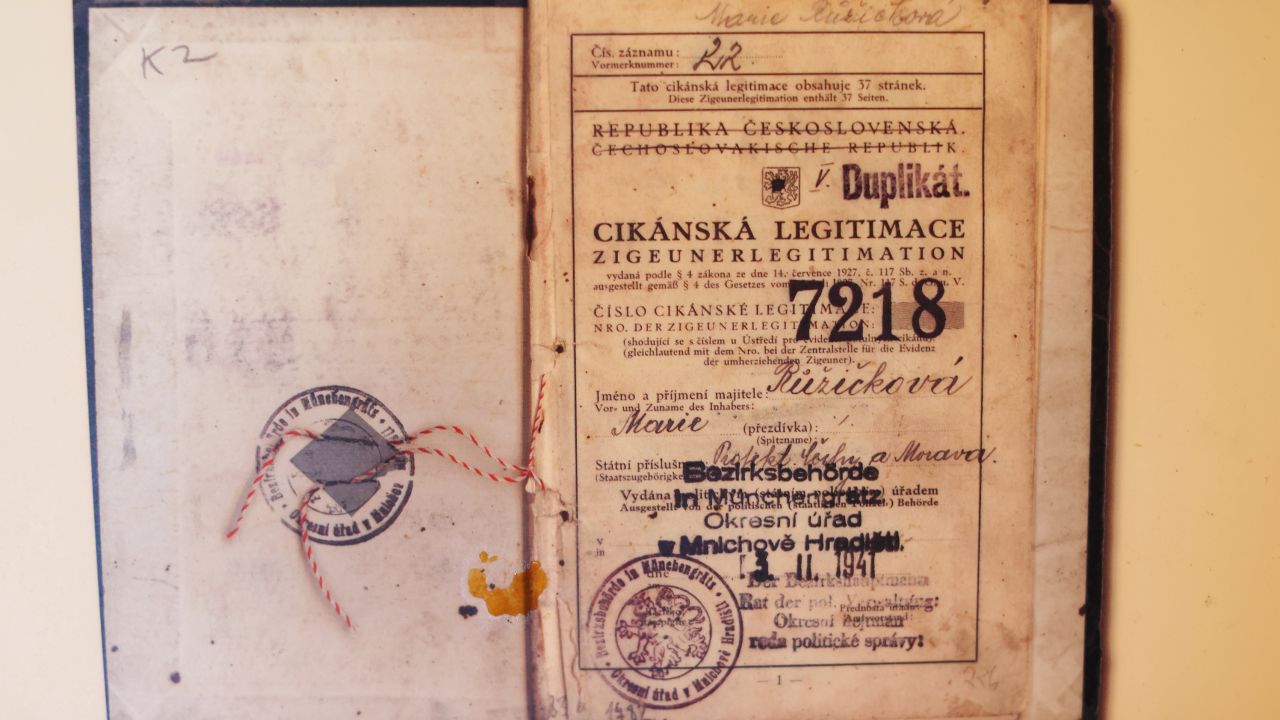

The Lety camp was one of two “Gypsy camps” operating in the German-occupied Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during World War Two. Roughly 1,300 Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti men, women and children were held there from August 1942 to August 1943, according to historical records. Sinti people are a specific subgroup of Roma people who came to Europe in the Middle Ages and settled in mainly German-speaking countries.

At least 326 people, most of them children, are known to have died there. When the rest were deported to the Nazis’ Auschwitz concentration camp following a typhoid epidemic, the camp was leveled and largely forgotten.

One of the prisoners held at Lety was Bětka Růžičková, Růžička’s mother and Kokyová’s grandmother. Bětka’s parents and her 4-month-old daughter died at the camp. She was sent to Auschwitz when she was just 19 and was the only one of her family to survive the war.

“When grandma came back, she must have felt this horrible emptiness. She came back completely alone. Everyone was dead, she had nobody, she had nothing. And she knew that part of the suffering was down to her own people, to Czechs,” Kokyová said.

According to Kokyová, Růžičková never spoke of what happened during the war. Even those closest to her had no idea about the existence of the camp in Lety until several years after the 1989 Velvet Revolution – which ended four decades of communist rule – when a foreign journalist approached Růžičková’s son, Čeněk Růžička, about it.

“He didn’t believe it at first. Of course we all knew that there were concentration camps in Germany, of course we knew about the Holocaust. But we had no idea that something like this was happening here, in our own country,” Kokyová said.

“They showed him the documents they found in the archives and took him to the farm. And he always said that that was the moment when he realized how little a human being, a Roma human being, means to the world.”

Růžička made it his mission to have the farm torn down, and replaced with a memorial. His infant half-sister is buried somewhere near the camp.

Like other victims’ families, Kokyová is convinced that the fact that the camp was run by Czech people was one of the reasons for the hesitation around establishing a memorial. “The Roma Holocaust, the genocide, was a German Nazi plan. But the camp was administered by Czech guards. It was the Czechs who tortured the people there,” she said.

Rudolf Murka, whose father was held at a Roma concentration camp in Hodonín u Kunštátu in Moravia before being deported to Auschwitz, echoes that sentiment. “We can tell ourselves that it was all done upon the orders of the Nazis, but the truth is, these camps were originally built by Czechs and the guards were Czech,” he said. Out of the 50 members of Murka’s family held in the camps, only six survived the war, he said.

“My father always said that the worst thing was when you were being tortured and killed by people who spoke Czech. When the guards barked at you in German, that was one thing, but when you knew it was your own people doing this, that was the worst,” Murka told CNN.

The Nazi genocide of Roma and Sinti people is sometimes referred to as “the forgotten Holocaust,” according to Jana Horváthová, a Czech historian and director of the Museum of Romani Culture in Brno, the Czech Republic’s second city.

Historians believe that between 25% and 70% of Europe’s Roma population was murdered during the war. In what is now the Czech Republic, as much as 90% of the original Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti population perished, according to historians.

Yet even West Germany only officially recognized the racial background of the Roma genocide in 1982, 30 years after formally acknowledging its responsibility for the Jewish Holocaust. On a wider European level, it took until 2015 for the European Parliament to pass a resolution formally recognizing Roma genocide.

Evidence of the scale of the crimes inflicted on Europe’s Roma population is still being collected and examined – and the estimates of the number of victims keep changing, Horváthová said, as more evidence is uncovered.

“It is unlikely that we will ever get the full picture of how many Roma and Sinti people were killed,” she told CNN in an interview at the museum’s headquarters.

New research into the May 1944 Roma prisoners’ uprising in Auschwitz is one example of new information shining more light on the scale of the genocide. “It’s always been thought that 2,897 Roma and Sinti were murdered in the gas chambers within the days following the demolition of the ‘Gypsy camp’ in Auschwitz. Now we know there were at least 4,300 victims,” she said.

Horváthová said that after the war, the Czechoslovak communist regime failed to acknowledge the Roma Holocaust and many survivors were afraid to speak about their experiences because of the stigma associated with being Roma.

Murka remembers secretive family visits to the remnants of the camps during the communist era. “We’d go at night or late in the evening when it was dark, we’d light a candle and put some flowers on the spot and then we’d go home. It wasn’t something people would be able to do openly, because they were so worried about persecution,” Murka said.

“During communism and even long after the revolution, nobody wanted to admit there was such a thing as a Roma Holocaust, it was not something you would speak about openly.”

That stigmatization continues today.

According to the most recent annual report from the Czech government’s Council for Roma Minority Affairs, Roma people are still by far the most marginalized minority group in the country. Official surveys quoted by the report show a majority of Czechs consistently rank Roma people as the “least likeable” minority group, behind Muslims and Russians.

Another survey quoted in the report said that 25% of Czechs said they wouldn’t let out their apartment to a large family with a typical Czech surname. When the surname was changed to a traditional Roma name, the number of those refusing to let it rose to 60%.

Zdenek Serinek’s grandfather, Josef Serinek, was also held at Lety, and was the only one of his entire family to survive the war.

Josef managed to escape the camp and, while on the run, became a prominent member of the Czech resistance movement. But despite taking part in a number of high-profile operations, Josef was not recognized in the same way other resistance fighters were after the war.

He only received the Czechoslovak Medal for Merit, which was awarded for non-combat actions. It took until 2022 for his actions to be recognized with the appropriate military award, the Medal of Heroism.

Zdenek said his grandfather’s heroism wasn’t a topic of discussion in the family. “Whenever we asked about him, people would just start speaking about something else. I think maybe they didn’t want us to be associated with a Roma ancestor, or maybe they just didn’t want to talk about the war experience.”

After the war, Josef married a fellow member of the resistance movement, Marie Zemanová, who did not have Romani heritage. Their children and grandchildren, including Zdenek, were brought up without learning much about their Roma ancestors.

“When I was born, my grandpa’s first question was what I looked like. My dad didn’t understand what he was asking and my grandpa said: ‘Is he Black or is he White.’ And my dad said ‘White’ and my grandpa said ‘good,’” Zdenek said.

The deep prejudices against the Roma community have plagued the debate around a Holocaust memorial in Lety.

After the collapse of the communist regime, Czech and Moravian Roma and Sinti people begun pushing for the state to officially recognize the Romani Holocaust and demolish the pig farm. Successive governments dodged the topic, claiming that it would be too expensive to buy the farm from its private owners in order to have it demolished.

For decades, even top-level officials questioned its history. Former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš was forced to apologize in 2016 for his claims that “it’s a lie to say the Lety camp was a concentration camp,” claiming the facility was for “people who didn’t want to work.” Václav Klaus, former president and prime minister, said that while “tragic things happened” at the camp, it was “not a real concentration camp in the sense that each of us subconsciously understands the word.”

Horváthová said that at first – and for a really long time – she didn’t believe Růžička’s campaign to have the farm torn down could be successful.

“In the late 1990s, it looked like there was no chance this would ever happen. The society was aggressively against it,” she said.

The Czech Republic was going through a dark period of heightened racial tensions when Růžička began his campaign in 1997. Racially motivated violence was not uncommon, with the Czech Helsinki Committee, a non-governmental human rights organization, warning at the time that violent acts of racism and discrimination against Roma people were growing in number and that the authorities were doing little to stop them.

When a group of skinheads drowned Roma teenager Tibor Danihel in Písek in 1993, it took years for the courts to classify his death as a racially motivated murder.

On May 13, 1995, President Václav Havel officially unveiled a makeshift memorial near the burial grounds adjacent to the camp in Lety, denouncing the fact that a piggery was allowed to be built there. On the same day, a group of skinheads brutally murdered a Roma father-of-five, Tibor Berki, after breaking into his family home in South Moravia.

Kokyová was a high-school student at the time. “When I was a freshmen there were three skinheads in the senior class. I would hear the rumors that they talked about me and said I should ‘look forward to going to school,’” she said.

“I still remember the feeling. Our classroom was on the first floor but we had some classes that took place on the third floor, where their classroom was. I never, ever walked there alone. I never admitted it to my friends, I just made sure I was never alone,” she said.

Berki’s murder eventually led to changes in Czech law. Harsher punishments were introduced for racially motivated violence and prosecutors adopted a tougher approach.

However, it took another two decades for the government to finally act on the most obvious symbol of anti-Roma discrimination, the Lety pig farm.

“At some point, in 2017 or so, it became obvious that the society was now on our side… maybe we needed all this time to get to the point where it becomes unacceptable to have a pig farm there,” Horváthová said. “Yes, it took three decades, which is very long time in a life of a person, but to me, it’s very, very positive news.”

Neither the Czech government nor the company that owned the farm responded to CNN’s question about why it took so long.

In 2018, the Czech state finally bought the farm for 450 million Czech crowns ($20 million), clearing the way for it to be demolished. A new, official Holocaust memorial is being built there and should open some time early next year. It will include a visitor center with an educational space and exhibition, and a large memorial meadow surrounded by forest marking the original site of the camp. A circular path around the space will feature the names of the camp’s known prisoners.

Partial remnants of the pig farm will also remain – a part of the memorial that was specifically requested by the victims’ families.

“It was incredibly important to us to maintain the memory of this. It’s part of the history of this place and it’s important to show it,” Murka said.

Archeological research conducted after the farm was acquired by the government – the previous owners never allowed excavations on their property – uncovered the remains of the camp and gave the public a glimpse of the horrors that occurred. It also provided proof that the camp’s remnants were clearly visible when the pig farm was built.

The research confirmed the prisoners were subjected to hard labor, an extremely poor diet and inhumane conditions. The discovery of an intact long plait of hair indicated prisoners’ hair was cut and shaved. A shallow grave containing the remains of a young woman and a baby was excavated nearby.

At the annual remembrance event in Lety in May, the newly elected Czech President Petr Pavel said it was important to “clearly describe” the dark periods in the nation’s history and “admit our share of guilt in it.” It was only the second time a president had attended the yearly memorial service, and came 28 years after Havel’s visit.

Růžička didn’t live to see this. He died in December last year, just months after smashing the pickaxe into the wall of the piggery during the ceremony marking the start of its demolition.

His niece said he died knowing something dignifying and beautiful was being built. “He was 76, but he still had a part of him that was youthful, and, maybe, a bit naive. He believed that people are inherently good and that justice will prevail,” she said.

Růžička’s main goal, she said, was accomplished. “I think he wanted the Czech nation to admit that this was a horrible thing. The top officials, in front of all the cameras, finally admitting that this was all wrong. We finally got to this point, where the nation itself sort of accepts its share of responsibility for this.”