CNN

—

It is the kind of unlikely love story that would make the scriptwriters of Asia’s biggest movie business proud. Despite thousands of miles between them, a romance has blossomed between Australia and Bollywood’s movers and shakers.

Earlier this year, Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese flew to Delhi to woo his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, on a range of subjects, including trade, defense and cricket.

One issue that made headlines was the announcement of a bilateral Audiovisual Co‑production Agreement which seeks to encourage collaboration and cultural exchange through Indian-Australian co-productions.

Or, as Australian arts minister Tony Burke put it, “bringing a slice of Bollywood to Brisbane.”

But the love affair is far from new, according to “Brand Bollywood – Downunder,” a documentary due to premiere this fall which looks at how the Indian film industry’s links with Australia have expanded since the late 1990s.

Indian-born Anupam Sharma, its producer, writer and director, first came to Australia to visit family as a child. Years later, in the 1990s, he enrolled at film school in Sydney, sub-majoring in acting.

“There was a distinct lack of opportunities,” he recalled in a video interview with CNN. “I was doing the usual thing, playing a doctor or a spice shop owner in a TV commercial.”

The picture has changed dramatically in the past quarter-century.

There has been evidence of that in the Australian city of Melbourne in recent days, as the red carpet has been rolled out for the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne, now in its 14th year and the largest of its kind outside India. More than 100 films in 20 languages will be shown over 10 days, alongside panel discussions, an awards night and a Bollywood dance competition.

As Sharma tells it, a chance encounter helped the early romance blossom.

In 1997, fate intervened when Sharma heard that Feroz Khan – or, as he describes him, “Bollywood’s Clint Eastwood” – was in town.

Impulsively, Sharma decided to ring around top hotels in search of the star. He struck lucky.

“I was praying it would go to answering machine and it did,” said Sharma. “I quickly thought if I say [I’m] an actor he won’t call me. So I said ‘this is Anupam Sharma, I’m a film consultant’.”

The brazen approach paid off and the following morning Khan’s assistant called for a meeting. This led to the pair spending three months together filming “Prem Aggan,” released the following year, which Khan wrote and directed and Sharma produced.

Things boomed from there, recalled Sharma, as Khan proved to be a trendsetter for the industry. Indian cinema-goers flocked to see Bollywood stars performing song and dance routines against a backdrop of the Sydney Opera House, the Twelve Apostles and other iconic landmarks, in a whole host of Indian movies filmed in the years that followed.

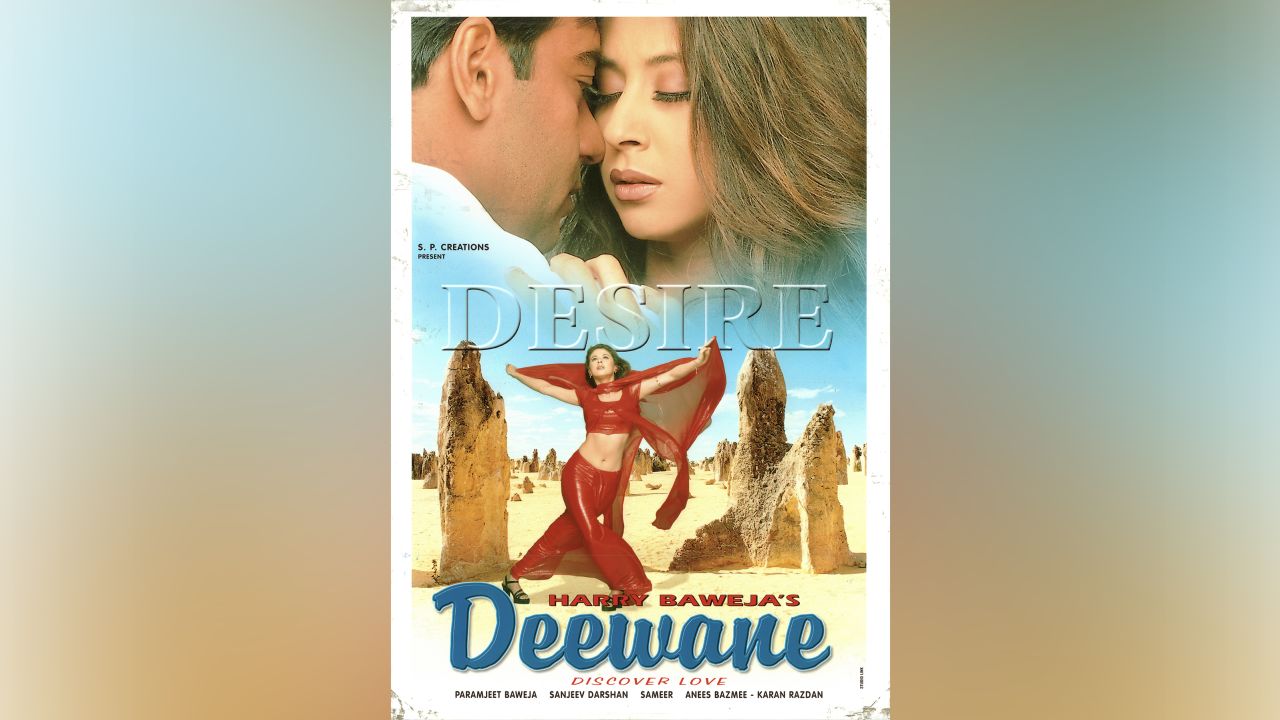

Harman Baweja starred alongside Priyanka Chopra in “Love Story 2050,” shot in South Australia and released in 2008. The shoot was such a big deal at the time that the then-state premier Mike Rann, who was instrumental in nurturing the relationship with Bollywood, landed himself a cameo role in the film.

In an email to CNN, Baweja said he and his father, filmmaker Harry Baweja, had filmed throughout Australia at “amazing locations backed by professional crews, government support that is efficient and tailor made for a seamless production environment.”

Soon the Australian authorities were flooded with requests for visas for future productions, but also tourists wanting to visit the movie locations.

“It was a huge Bollywood bandwagon,” said Sharma.

The honeymoon period ended in 2009 when diplomatic tensions emerged following what appeared to be racially motivated attacks on the growing number of Indian students in Australia.

But while feature film production slowed down, the appetite for co-working remained strong, according to Sharma.

“Australia realized that after ‘servicing’ Bollywood for over 13 years it was time to shift gears and move to collaboration with Indian cinema,” said Sharma. “So a lot of professionals like me started concentrating on shared stories and telling our Indian Aussie stories.”

This led to the emergence of movies like the award-winning “Lion,” “Hotel Mumbai” and Sharma’s own feature, “UnIndian,” a romance centered on an Australian woman of Indian origin, which he describes as “Western body, Indian soul.”

“It means films made with a Western beat – around 90 minutes long, not the three hours of Bollywood. The distribution, the financing, the structures, the editing are Western, but the soul, the emotions, the music, the drama is still Indian.”

Sharma admits that the term “Bollywood” sometimes ruffles feathers.

“There are people who would swear at me for saying the word Bollywood,” he said, explaining that many find the term demeaning. “The industry is like an Indian goddess with many different arms.”

Australia already has 13 formal co-production partners, including Canada, China and the UK. If India follows suit, it will allow co-production access to direct and indirect government funding including grants, loans and tax offsets.

Once the Audiovisual Co‑production Agreement is ratified by both the Australian and Indian parliaments, a process that could take several months, the arrangement could be hugely lucrative for both sides – as well as culturally valuable for both Australian and Indian filmmakers.

Welcoming the anticipated move, Lion’s Australian director Garth Davis said in an email to CNN: “I adore filming in India. Not only is the country rich in history, humanity and spirit, the skill level in this industry is exceptional. Working together only enriches us, and if these treaties create a more fluid approach through the willingness and openness of these two countries, then that is very exciting.

He added: “‘Lion’ is the perfect example of the two countries working together in such a beautiful way, and I am certain I will be back there again.”

Brothers Salim and Sulaiman Merchant, Mumbai-based composers and musicians who produced the music for “UnIndian” and Sharma’s upcoming documentary, are similarly keen to see more collaborations.

Salim Merchant told CNN he loves Australia’s “vibe,” adding: “I think it’s wonderful there’s that synergy.

“Film is a beautiful medium. Making films that have both the diverse cultures and traditions creates a lot of love and respect between the two countries.”

Of no little importance is the growing audience for Bollywood productions in Australia.

Set up in 2010 by Mitu Bhowmick Lange and her film distribution company Mind Blowing Films, the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne proved so successful that the Victoria state government came on board in 2012.

“I came here in 2001 when India was not as cool and fashionable as it is now,” Bhowmick Lange told CNN.

“The first Hindi film I saw was in China Town, in a community hall. There were two cardboard boxes: in one you put cash and in the other were samosas.”

Bhowmick Lange says she set up her business and the festival partly due to “my own need to watch Indian films.”

She is obviously not alone. According to the most recent figures, the Indian-born population is the second largest migrant community in Australia after the British, equivalent to 9.5% of Australia’s overseas-born population and 2.8% of Australia’s total population.

Bhowmick Lange has produced numerous films including “Salaam Namaste,” shot in Melbourne in 2005. A romantic comedy, it told of two Indian students who enrolled at the city’s La Trobe University.

“There were ‘Salaam Namaste’ tours and La Trobe said they got so many calls from people interested in coming to study from India,” she recalled.

As well as the financial benefits of the co-production deal, both sides hope to appeal to the “other,” according to Sharma.

“Australia wants to boost its diversity credentials,” he said. “Meanwhile, one of my friends said Bollywood is not after a wider audience, but a Whiter audience.”

A controversial point, perhaps.

That said, Bhowmick Lange said festival-goers no longer hail just from the city’s Indian community, proving film is a “beautiful bridge between the two countries.”

“The world is getting smaller and smaller and streaming has changed everything,” she said. “Everyone’s used to reading subtitles and watching foreign shows – I think the global appetite has changed.”

That must be a good thing, Bhowmick Lange believes, as she has “never understood the Western snobbery” about Bollywood.

“If a person who earns two dollars a day can forget all his problems for three hours and access this beautiful world which just takes him away from that, that should be celebrated not frowned upon,” she argues.

Hopeful of the potential of the new treaty, Sharma adds: “Indian films have always been a universal language for foreign governments to engage with India.

“Australia is one of the most professional film industries in the world. India, undoubtedly, is one of the most prolific film industries in the world. And the marriage between the two has to be a win-win for both.”