“Perhaps if I hadn’t had to fight, I would have quit,” the artist Joan Mitchell once said. “I don’t know. I doubt it, though.”

Mitchell’s work may have been born out of struggle, but there is no question that she was able to prevail, creating paintings now considered 20th century masterpieces.

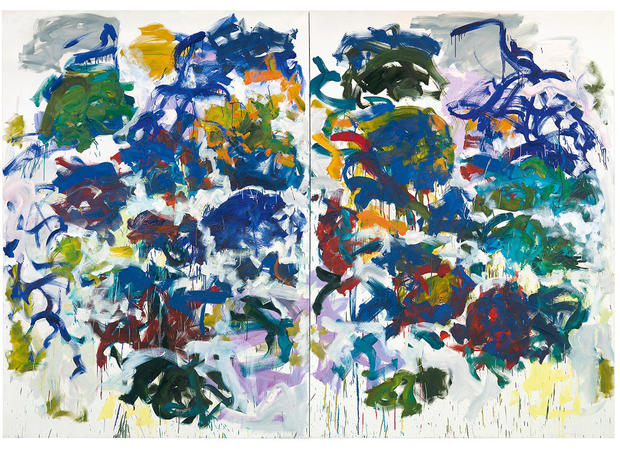

And Katy Siegel, who co-curated a show of Mitchell’s work for the Baltimore Museum of Art, says that it is, in part, an effort to place Mitchell in the pantheon of other abstract expressionists (such as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollack, Grace Hartigan and Lee Krasner) who exploded onto the New York Art Scene in the 1950s. “Her work is strong, muscular, declarative, aggressive,” said Siegel. “It is everything that abstract expressionist thought that it wanted to be.”

CBS News

Correspondent Rita Braver asked, “She was one of several important women artists who exhibited at that time. Yet it seems like it was the men who got all the attention. Why was that?”

“Well, it’s not rocket science to figure out why; it was just plain old sexism,” Siegel replied.

Still, Joan Mitchell always charted her own course. She was born in 1925 to a well-to-do Chicago family – her father a doctor, and her mother the editor of poetry magazine.

Siegel said, “She did athletics, she was a champion ice skater, she went to the symphony, she went to the Art Institute of Chicago. It was a life of culture.”

“It seems like she developed an early interest in both art and poetry,” said Braver. “And when she was 11 years old, her father told her she had to choose one? Is that true?”

“It is true. And he said, ‘You have to be great to be great at something. You can only do that one thing.’ And she chose.”

Mitchell would never look back.

While her early work was figurative, by the time she was 25 and living in New York, she was moving further into abstraction: “She paints ‘Figure and the City’ in 1950, and she said, ‘I knew that it would be my last figure,'” Siegel said. “And it was.”

© Estate of Joan Mitchell / Joan Mitchell Foundation

In 1959 Mitchell moved to Paris, where she made making increasingly larger works. A decade later, she bought a country estate in the village of Vétheuil, where the French Impressionist Claude Monet had once painted.

Braver asked, “How has her work evolved by this time?”

Siegel said, “For one thing, that idea that she uses all colors, the full spectrum, has really developed here. And a really amazing use of white that just lights up the painting.”

“Would she have been okay for me to say it’s gorgeous?”

“Yes, she was not afraid of beauty, unlike most people in her generation,” said Siegel. “And as she said, ‘I’m not of the make-it-ugly school.'”

© Estate of Joan Mitchell

Mitchell was described as both charming and cantankerous. Her love life was tumultuous. A heavy drinker and smoker, she suffered from depression. And, often traveling between France and the U.S., she said she always felt like an outsider, as she told documentary filmmaker Marion Cajori in 1992: “In France, I’m an American gestural painter, and lyric on top of it, which is very pejorative. And here, I’m a Frenchie, because I have color, and decorative, ooh, ooh! So, you can’t win,” she laughed. “And on top of it, I’m a girl, a woman, a female!”

Robert Freson/Joan Mitchell Foundation Archives. © Joan Mitchell Foundation

However Mitchell thought she was seen, artists like Stanley Whitney, 20 years younger, acknowledge her influence. “She’s a painter’s painter,” he said.

Braver asked, “What did you want to learn from her?”

“The freedom,” Whitney replied. “And I wanted the color, and I want the space, the timing of it, the rhythm of it.”

And, he says that works like “Sunflowers” show how skilled Mitchell became: “It’s magical how much she gets done by just making a mark. She knows so much about painting that she has total freedom to do whatever she wants.”

Joan Mitchell never got to see the prices of her work skyrocket, with “Blueberry” selling for $16.6 million in 2018. She died of lung cancer in 1992 at age 67.

Siegel said, “Even though she died early, you know, that’s almost five decades of painting, but also the model of a life lived incredibly intensely. If art was at the center of her life, life is really at the center of her art.”

© Estate of Joan Mitchell

For more info:

Story produced by Julie Kracov. Editor: Chad Cardin.