The U.S. is acknowledging the large-scale and violent treatment of Indigenous students at more than 400 Indian boarding schools run by the federal government between 1819 and 1969, according to a report released by the Department of Interior on Wednesday.

Over 500 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children’s deaths occurred at 19 of the federal Indian boarding schools, according to the report. In total, 53 marked and unmarked burial sites were identified at these school facilities nationwide. The investigation is ongoing, and the department said it expects “the approximate number of Indian children who died at Federal Indian boarding schools to be in the thousands or tens of thousands.”

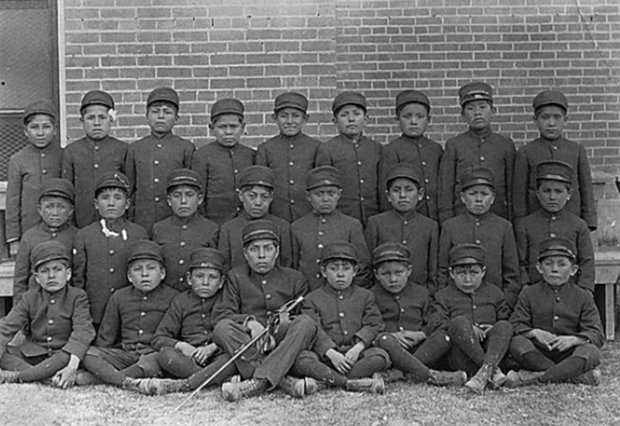

Beginning in the early 19th century in the U.S., Indigenous children were “selected” from reservation schools and moved away from their families to attend the government-chartered schools, which were often subcontracted to Presbyterian, Catholic and Episcopalian religious organizations to operate, the report said.

National Archives

The Indian boarding schools, which were often located at active or decommissioned military sites, separated children from their families and forced them to abandon their native language and culture through what the report termed “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies.”

The children had their hair cut and were given English names. They were forced to adhere to strict schedules that included lessons in English, obedience, cleanliness and Christianity.

According to the report, each day was so strictly systemized that there was “little opportunity to exercise any power of choice.”

When children failed to meet school standards or broke rules, they were “subject to corporal punishment, including solitary confinement; flogging; withholding food; whipping; slapping; and cuffing.” Older children were forced to inflict punishment on younger children.

The report detailed “rampant physical, sexual, and emotional abuse; disease; malnourishment; overcrowding; and lack of health care.” At some boarding schools, several children were forced to sleep in one bed.

The Interior Department report identified 408 federally run schools in 37 states. Oklahoma had the highest number of schools, with 76, followed by 44 in Arizona, 43 in New Mexico and 30 in South Dakota.

National Archives

The Interior Department said it is not publicly detailing the locations of the children’s burial sites “in order to protect against well-documented grave-robbing, vandalism, and other disturbances to Indian burial sites.” But it is working to notify tribes of the burial sites.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland released the first volume of the 106-page investigative report as part of the 2021 Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

“This report places the Federal Indian boarding school system in its historical context, explaining that the United States established this system as part of a broader objective to dispossess Indian Tribes, Alaska Native Villages, and the Native Hawaiian Community of their territories to support the expansion of the United States,” Newland wrote. “The Federal Indian boarding school policy was intentionally targeted at American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children to assimilate them and, consequently, take their territories.”

These boarding schools operated with congressional funding and used housing provided by the federal government. In 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act was passed in order to try to keep Native American children with their families, rather than removing them. By 2019, there were only four boarding schools operated by bureau of Indian Education, and they are no longer tasked with assimilating the students.

Wednesday’s report also notes the history of the Interior Department’s slow response to the horrible boarding school conditions. It quoted the department’s acknowledgement of “progress” in 1897 when at “the great majority of schools” students were given their own towels, combs, hairbrushes, and toothbrushes, rather than being forced to share toiletries.

Children were subject to hours of daily vocational training including livestock and poultry raising, dairy work, lumber and carpentry, blacksmithing, irrigation system development, cooking and railroad construction.

Walter J. Lubken/U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Phoenix Area Office

These boarding schools also instructed non-Indians, including emancipated Black people known as “Freedmen,” the report said, and it concluded that the federal Indian boarding school system “continues to impact the present-day health” of former students alive today.

“Now-adult attendees were more likely to have cancer (more than three times), tuberculosis (more than twice), high cholesterol (95 percent), diabetes (81 percent), anemia (61 percent), arthritis (60 percent), and gallbladder disease (60 percent) than non attendees.”

In response to these findings, Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet secretary, is starting the “Road to Healing,” described as a “year-long” tour across the country to hear and support federal boarding school survivors, as well as collect a permanent oral history.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policiesâincluding the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years oldâare heartbreaking and undeniable,” Haaland said in a statement. “We continue to see the evidence of this attempt to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people in the disparities that communities face. It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”