The Dua Lipa song, “Levitating,” has now been on the pop music charts for 72 weeks in a row. But a band called Artikal Sound System is suing her for stealing one of their songs, “Live Your Life.”

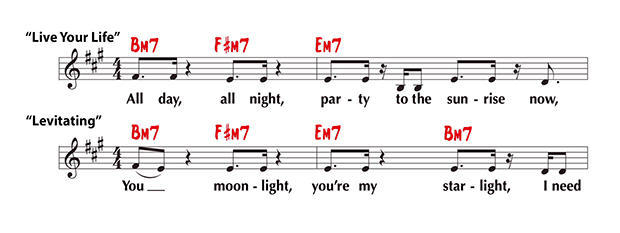

The two songs have the same key and tempo, same melody, and same chords.

CBS News

These lawsuits have a history. The first big one to go to trial was the Chiffons (“He’s So Fine”) vs. George Harrison (“My Sweet Lord”). Harrison lost, and paid over half a million dollars.

But here’s the thing: When you write a song, you don’t have a lot of notes to choose from. And most songs use only a few chords. Inevitably, sooner or later, two people will write songs with sections that sound alike, right? Should there even be lawsuits?

Lawyer Richard Busch asked correspondent David Pogue, “How many letters are there in the alphabet?”

“Twenty-six.”

“And how many words can you create out of those 26 letters? Billions? Millions? Right? So, I don’t care how many notes there are, or how many chords; there is an infinite number of ways to mix those notes up, to mix those chords up, to create original music.”

Busch has sued several famous bands for stealing, and he’s won every time, including the “Blurred Lines” case.

To Jan Gaye, the 2013 hit “Blurred Lines,” by Robin Thicke and Pharrell Williams, sounded an awful lot like a 1977 song called “Got to Give It Up,” by her ex-husband, Marvin Gaye. “It was a nightmare,” she said. “I lost a lot of faith in people, and their motivations in the music business.”

Pogue asked, “No one needed to convince you of how much it sounded like ‘Got to Give It Up’?”

“Not for a moment,” Gaye replied. “No, I was there when Marvin made the record, so there was no hesitation, no confusion.”

Richard Busch won the case. The Gaye family got $5 million and half of all future royalties.

What made the “Blurred Lines” case so notorious is that the two songs aren’t technically that much alike. The melodies and lyrics are different; the chords and bass lines are different. What they do have in common is their vibe: the beat, the cowbell, the party chatter.

The verdict seemed to open the doors for similar lawsuits against famous bands.

In 2016, a band called Collage (“Young Girls”) sued Bruno Mars and Mark Ronson (“Uptown Funk”) and won a settlement.

Martin Harrington and Thomas Leonard (“Amazing”) sued Ed Sheeran (“Photograph”) and won co-writing credit and royalties.

Now, to win one of these lawsuits, you have to prove three things: first, you have to prove that you own the original song; second, you have to prove that the thief had access – that they heard your song at some point; and finally, the big one, you have to prove that the two songs are substantially similar.

And that’s where things get tricky.

Lawyer Ilene Farkas has represented songwriters who are accused of stealing songs. “No one can own individual notes,” she said. “No one can own chord progressions. No one can own a guitar riff. No one certainly can own a feel of a song.”

She argues that there’s a difference between copying and inspiration: “The Beatles were inspired by Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones by the great Delta Blues artists and Robert Johnson, Elvis by B.B. King. They put their own spin and modern-day approach to it. And that’s what creativity is about.”

Damien Riehl, a musician, lawyer, and programmer, showed Pogue a hard drive: “On this hard drive is 68 billion melodies that arguably include every melody that’s ever been written, and every melody that ever can be written.”

He and a friend wrote a software program to generate those 68 billion melodies, to make the point that suing over a snippet of a song is absurd. “What we’ve done is taken all of these songs, all of these melodies, and placed them all in the public domain,” Riehl said, “so that anyone could be able to use them freely, without having to worry about getting sued.”

Pogue asked, “How far would you go with this thought of ‘These lawsuits are silly?’ Like, I just wrote a song that goes, ‘Saturday, all my dalmatians seemed so far away!’ Like, is that OK?”

“Absolutely not!” Riehl smiled. “If someone steals an entire song, yes. Sue those people for all they’re worth! But for very short phrases of melodies, and perhaps even longer melodies, they should not be copyrighted.”

Farkas isn’t sure that that hard drive full of melodies would hold up in court. But maybe the stunt made its point. In more recent lawsuits, the pendulum has begun swinging back. “I feel like there’s been a bit of a course correction in the cases that have followed ‘Blurred Lines,'” she said.

When a band called Spirit (“Taurus”) sued Led Zeppelin (“Stairway to Heaven”) in 2014, they ultimately lost. And when a rapper called Flame (“Joyful Noise”) sued Katy Perry (“Dark Horse”) in 2019, he lost on appeal, too. The judge wrote that those eight notes are “not a particularly unique or rare combination.”

Farkas said, “Those are two great examples of courts that said, ‘We’re not going to start dissecting music and hunting for similarities so that we can hand out ownership to pieces of music.’ No one wins if that happens.”

And so, in the Dua Lipa case, what would you decide if you were the judge?

Richard Busch knows what he thinks.

Pogue asked, “There are people who believe that there shouldn’t be any lawsuits over copyright infringements, that ‘good artists copy, great artists steal,’ that we build on existing works.”

Busch laughed: “People who say that probably haven’t had their stuff stolen!”

For more info:

Story produced by Gabriel Falcon. Editor: Lauren Barnello.

See also: