CNN

—

The American Museum of Natural History in New York will remove all human remains displayed in its exhibits and is preparing a new storage location for its collection of 12,000 remains – which includes skeletal remains of Indigenous and enslaved Black people – according to a letter from the museum president obtained by CNN.

“We must acknowledge that, with the small exception of those who bequeathed their bodies to medical schools for continued study, no individual consented to have their remains included in a museum collection,” museum President Sean M. Decatur said in the letter to staff.

In the recently updated collections policy, the museum stated it will not knowingly acquire “any item or lot that was collected or recovered under circumstances that would support or encourage irresponsible damage to or destruction of archeological sites, cultural monuments, or defilement of human burial places.”

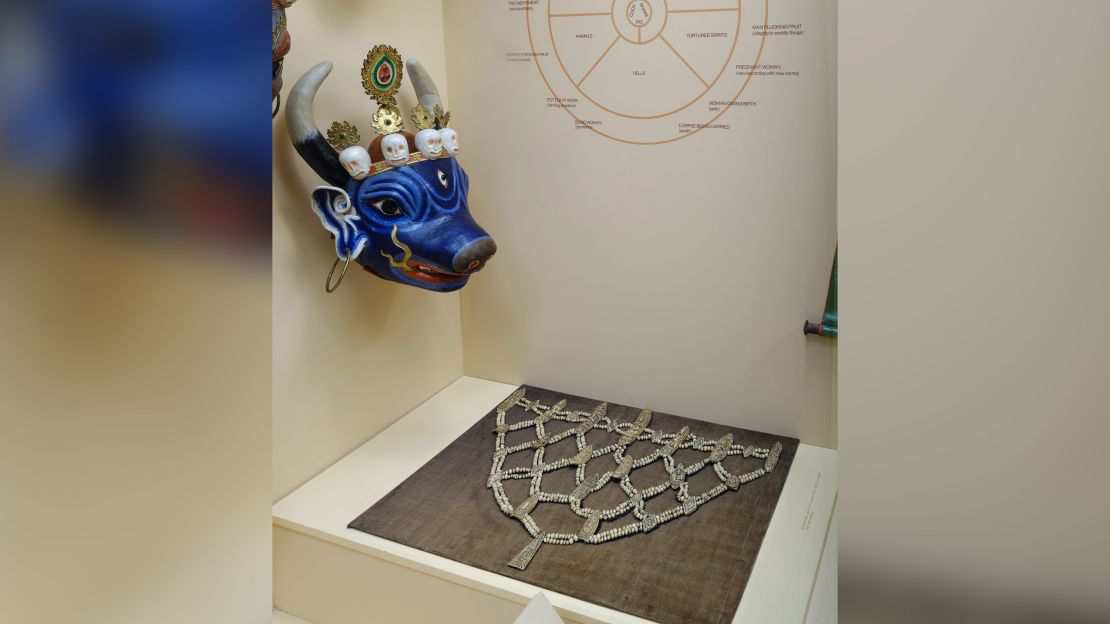

Skeletons and mummies will be removed from 12 display cases, as well as musical instruments and beads made from or incorporating human bones, Decatur said.

Of the thousands of skeletal remains in the museum’s collection, 26% are of Native Americans from within the United States, Decatur said in the statement. Most of the other remains are from abroad, he added.

The museum also holds the remains of five enslaved Black people that were removed from a New York burial ground during a road construction project in the early 1900s, the letter said.

What the museum has on display is only “a very small percentage” of its full collection of skeletal remains, museum spokesperson Kendra Snyder said in a statement to CNN.

That includes a complete human skeleton that’s on display in a reconstruction of the burial of a warrior from Mongolia in about 1000 CE, a 19th-century Tibetan apron made of human bone, and, in the Hall of Mexico and South America, instruments made from human bones in a display about Aztec musical instruments, Snyder said.

“None of the items on display are so essential to the goals and narrative of the exhibition as to counterbalance the ethical dilemmas presented by the fact that human remains are in some instances exhibited alongside and on the same plane as objects,” Decatur said in the letter.

“These are ancestors and are in some cases victims of violent tragedies or representatives of groups who were abused and exploited, and the act of public exhibition extends that exploitation.”

The policy change, Decatur said, is an attempt to address the “complex legacy of the human remains collection” and how the priority going forward will focus on properly storing the remains until repatriation can occur.

“Even in instances where the exhibit elements are cultural objects, this is the appropriate step to take while we reevaluate our stewardship of collections of remains of once-living individuals,” he added.

In the letter, the museum acknowledged researchers in the 19th and 20th centuries used remains to advance “deeply flawed scientific agendas rooted in white supremacy – namely the identification of physical differences that could reinforce models of racial hierarchy.”

“Human remains collections were made possible by extreme imbalances of power,” Decatur said.