SANFORD – There is nothing near the light brown and gold block buildings of The Retreat at Twin Lakes to note that this is where Trayvon Martin was killed a decade ago.

On a late afternoon in mid-December, children walk and laugh along a sun-brightened sidewalk on the outer edge of the townhouse complex. An elementary school sits across the street, and a park is not far from it.

The area has a hint of affluence – or, at least, of comfort.

Trayvon Martin: Florida race relations 10 years later

USA Today Network of Florida will host a panel discussion looking at race relations across the state.

Rob Landers, Florida Today

Nothing in this part of town speaks to one of the most notorious killings in modern American history, one that offered up yet another reminder that Black and white Americans view safety, the country’s judicial system, and the very notion of fairness in starkly different ways.

Trayvon’s killing – and the delayed arrest and eventual acquittal of the man who shot him – uncorked a wave of protests led not by the gray and grizzled leaders of civil rights battles of old but by a new, social media-savvy generation of activists.

The name Trayvon Martin preceded those of Jordan Davis, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Samuel DuBose, Corey Jones, Philando Castille, Elijah McClain, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd on a continuum of killing that has outraged Black Americans but has frequently been met with delayed arrests and unattempted or unsuccessful prosecutions.

From 2013: ‘Justice for Trayvon’ rallies in 100 cities across USA

Recently: Trayvon Martin’s mother visits Black Lives Matter tribute at Riviera Beach church

Those deaths inspired a statement from Black America that has become an exhortation: Black Lives Matter.

Sanford, a town of 60,000 people located about 28 miles northeast of Orlando, crept warily and grudgingly onto the national stage in the wake of Trayvon’s killing.

But Trayvon – locked in boyhood, locked in that hoodie for all time by the bullet George Zimmerman fired into his chest – is not in the tree-lined, more affluent parts of Sanford.

How Black Lives Matter went from a hashtag to the largest movement in US history

From Trayvon Martin to George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter movement continues to highlight Black lives lost to police and racial injustice.

Just the FAQs, USA TODAY

To see some of Trayvon, to feel a touch of what his death and the circumstances that followed it meant, a visitor would have to go to Goldsboro, a historic Black community not far from where the teenager was killed on Feb. 26, 2012.

Sanford: A town divided

Goldsboro used to be a town.

Local Black men and women, some connected to the Reconstruction Era Freedmen’s Bureau, founded the town in 1891, only 26 years after the end of the Civil War.

The sons and daughters of the formerly enslaved worked in agriculture, at railyards, set up their own businesses. Many registered to vote, an act of courage at a time when white Southerners were pushing back violently against the notion of sharing the franchise – and full citizenship – with the descendants of people they once owned.

In its first decade and a half, Goldsboro grew from a couple dozen residents to more than 100.

But Goldsboro’s days of incorporation were numbered.

The threat to the town came not from within but from the designs of the leaders of nearby Sanford, whose plans to expand were harmed by the secession of another community in the city, Sanford Heights.

Sanford, however, had friends in high places.

One of Sanford’s former mayors, Forrest Lake, was now in the Florida House of Representatives, where he pushed to limit Sanford Heights’ ability to incorporate. He then turned his sights to Goldsboro.

Stone markers outside the Goldsboro Museum in Sanford, Florida carry the names of Trayvon Martin and other Black people killed under questionable circumstances. There are no other memorials to Trayvon anywhere else in Sanford. (David Tucker / Daytona Beach News-Journal)

Stone markers outside the Goldsboro Museum in Sanford, Florida carry the names of Trayvon Martin and other Black people killed under questionable circumstances. There are no other memorials to Trayvon anywhere else in Sanford. (David Tucker / Daytona Beach News-Journal)

Knowing Lake and his colleagues in the Legislature wanted to find a way for Sanford to annex Goldsboro, leaders in the town started a letter-writing campaign to preserve their status.

It didn’t work.

In 1911, the Legislature passed a bill stripping both Sanford and Goldsboro of their incorporation. The bill reorganized Sanford as a city that included Goldsboro.

With that, Goldsboro – a source of great Black pride – was gone, swallowed up by a bigger, better-connected, white-led city.

Goldsboro’s streets had been named in honor of people important to its founding, but, after Sanford was allowed to subsume it, Sanford renamed those streets.

Clark Street, named in honor of Goldsboro’s founder, William Clark, became Lake Avenue.

Lake would later serve more than seven years in prison for bank fraud and embezzlement.

Still, it would take a century for the residents of Goldsboro to get the street name changed back to honor Clark.

That history – and a great deal more – is on display at the small local museum led by Pasha Baker, who serves as the Goldsboro Museum’s director and chief executive officer.

Black residents of Goldsboro know the community’s history, which still fuels anger and resentment.

“Up until Trayvon, there was a 100-year war between the Blacks of Goldsboro and the whites of Sanford,” said Francis Coleman Oliver, a retired teacher who has collected artifacts for 60 years – some at considerable, personal expense – and donated them to the Goldsboro Museum. “Blacks of Goldsboro said they weren’t going to have anything to do with the whites of Sanford.”

Florida Pulse: Trayvon Martin 10 year anniversary discussion

Trayvon 10 years later: Panelists discuss the effect Trayvon’s death had on them

Trayvon 10 years later: ‘State sanctioned’ violence against black community

Trayvon 10 years later: Can “The Media” do better with race issues?

Trayvon 10 years later: Is Stand Your Ground a threat to black men?

Trayvon 10 years later: Is there a continuing fear of black men in America?

Trayvon 10 years later: Is Stand Your Ground a necessary law?

Trayvon 10 years later: Killing strengthened Black Lives Matter movement

Trayvon 10 years later: “The media” has no idea what it means to be black

Trayvon 10 years later: Local media doing a better job at bringing the truth than national

Trayvon 10 years later: Killing galvanized America’s black youth

Trayvon Martin shooting 10 years later: ‘The talk’ Black parents have

Trayvon 10 years later: Addressing mental health in the black community

Trayvon 10 years later: What’s next for race relations?

Trayvon Martin shooting: Florida race relations, what’s changed?

In the weeks after Trayvon Martin was killed, leaders in Sanford would be forced to acknowledge the rage and pain that simmered in Goldsboro.

News crews would be set up on Sanford’s streets. National civil rights figures called for justice. And, across the country, young activists – seeing something of themselves in Trayvon – began organizing and marching and protesting.

Sanford was in the spotlight, and that spotlight was beginning to burn.

Fatal shot heard ’round the world

George Zimmerman: Hey, we’ve had some break-ins in my neighborhood, and there’s a real suspicious guy – it’s Retreat View Circle. The best address I can give you is 111 Retreat View Circle. This guy looks like he’s up to no good, or he’s on drugs or something. It’s raining and he’s just walking around, looking about.

Sanford Police dispatcher: Okay, and this guy is he white, Black, or Hispanic?

Zimmerman: He looks Black.

Dispatcher: Did you see what he was wearing?

Zimmerman: Yeah. A dark hoodie, like a gray hoodie, and either jeans or sweatpants and white tennis shoes …

On Feb. 26, 2012, then-28-year-old George Zimmerman, a neighborhood watchman at the Retreat at Twin Lakes, shot and killed Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old from Miami Gardens visiting his father and his father’s fiancée in Sanford.

Family photo

Trayvon, the world would learn, was on his way back from a trip to a convenience store, where he bought a bag of Skittles candy and a can of watermelon-flavored drink.

He was unarmed.

Zimmerman had told a police dispatcher at one point that he was following Trayvon, suspecting him of possibly being involved in break-ins that were occurring in the community.

The dispatcher told Zimmerman, “We don’t need you to do that.” But Zimmerman and Trayvon still somehow came together on that rainy night.

“These assholes, they always get away,” Zimmerman would tell the dispatcher.

No evidence would emerge that Trayvon was involved in break-ins in Sanford. While the teen had gotten into some trouble at his school – trouble his parents punished by forcing him to sit out football games – he had no criminal record.

His father, Tracy Martin, said 9-year-old Trayvon once saved his life by pulling him out of a fire in their apartment.

In “Rest in Power,” a 2017 book Martin co-wrote with Sybrina Fulton, his ex-wife and Trayvon’s mother, the father described his son and the pain of his loss.

“The child I lost was a son, a boy who hadn’t yet crossed the final threshold to becoming a man,” Tracy Martin wrote. “He had been 17 for only three brief weeks, still in the beautiful and turbulent passage through childhood’s last stages, still on his way to becoming. Instead, he will be remembered for the things he left behind.”

Unlike Trayvon, George Zimmerman does have an arrest record.

In July 2005, he was arrested and charged with resisting an officer after a scuffle with police near the campus of the University of Central Florida. That charge was dropped when he agreed to participate in an alcohol abuse education program.

He had been 17 for only three brief weeks, still in the beautiful and turbulent passage through childhood’s last stages, still on his way to becoming. Instead, he will be remembered for the things he left behind.

In August 2005, Zimmerman’s former fiancée sought a restraining order against him, alleging domestic violence. Zimmerman responded by seeking a restraining order against her. Both orders were granted, and no charges were filed.

Despite that history, Zimmerman was not immediately arrested and charged after he shot Trayvon.

He claimed he and Trayvon were in a struggle and that he was defending himself against the teen, who was 5 feet, 11 inches tall and 158 pounds at the time of his death. (Zimmerman, 11 years older, was 5-foot-8 and 200 pounds the night he killed Trayvon.)

An officer who arrived at the scene of the shooting reported that Zimmerman’s back was wet and covered with grass and that he was bleeding from the nose and the back of his head.

There are pictures of Zimmerman from that night with a busted, swollen nose and blood from what appear to be abrasions on the back of his head.

David Tucker/USA TODAY NETWORK

Another officer said he heard Zimmerman say he yelled for help, but Trayvon’s parents would later insist that the person yelling in a recording of the killing was their son.

Zimmerman would be questioned by Sanford Police for five hours and then released.

Previously: Calls for repealing ‘stand your ground’ hit Florida Capitol

Sanford Police Chief Bill Lee said there was no evidence to dispute Zimmerman’s claim that he shot Trayvon in self-defense. Lee cited Florida’s “stand your ground” law, which says those who believe they face a threat of great bodily harm or death do not have to retreat and can use deadly force in their own defense.

Trayvon was dead. And the man who shot him to death was interviewed and released before Trayvon’s parents even knew their son was gone.

‘Wasn’t nothing going to happen to that white man’

Goldsboro residents said that, in the hours after Trayvon’s death, word began to trickle out.

A Black boy was killed at The Retreat. Police don’t know who the boy is, and no one is in custody for his killing.

Rage didn’t fire like a charcoal briquette. It built slowly as hour after hour went by with no identification of the boy and no arrest of the white and Peruvian man who shot him.

“We were in church on Sunday,” lifelong Goldsboro resident Michelle Wynn remembered. “They made an announcement because they didn’t know who he was. It was going around, like, ‘Whose child is this?’”

History informed some local Black expectations of an arrest.

“We weren’t marching,” Wynn said. “We weren’t protesting. We live here. Wasn’t nothing going to happen to that white man.”

It would take two days for police to identify Trayvon Martin as the teen killed by Zimmerman.

According to “Rest in Power,” they learned his identity when Tracy Martin sought to file a missing persons report with Sanford Police on Feb. 28.

After learning of the circumstances of his son’s death, Tracy Martin and a growing number of people across the country expected an arrest.

Their expectations would be met with inaction.

We weren’t marching. We weren’t protesting. We live here. Wasn’t nothing going to happen to that white man.

In comments many Black people thought blamed Trayvon for his own killing and showed inappropriate empathy toward Zimmerman, Sanford Police Chief Bill Lee was quoted in The Miami Herald saying: “I’m sure if George Zimmerman had the opportunity to relive Sunday, Feb. 26, he’d probably do things differently. I’m sure Trayvon would, too.”

Mark O’Mara, an Orlando attorney who would later represent Zimmerman, said his client did get a benefit of the doubt a Black suspect likely would not have gotten.

“Do I think George got some benefit because he’s white? Yes, I think he did,” O’Mara said.

Police, O’Mara said, were also looking to adhere to the “stand your ground” law, which he said directs law enforcement not to make an arrest if a person has a legitimate claim of self-defense.

None of that stemmed rising anger.

Zimmerman’s initial legal advisors fueled that anger by pillorying Trayvon, O’Mara said.

“They were blaming Trayvon for what happened,” O’Mara said. “It was a stupid tactic to take, to attack a child. They took this tactic that added a lot of fuel to the fire.”

O’Mara himself would later face criticism for leaning on race in defense of Zimmerman.

In the weeks after Zimmerman killed Trayvon, Black outrage swelled over the lack of an arrest.

Established civil rights figures made speeches, called for an arrest and justice.

But a new, younger generation of activists emerged using new platforms and tactics that would be repeated long after Trayvon’s death.

Black outrage’s new, younger face

Daniel Maree, a former Gainesville resident who had graduated from American University in 2008, organized the Million Hoodie March, using Twitter and YouTube to draw attention to the case and get people to sign a petition on Change.org calling for Zimmerman’s arrest and prosecution.

Heeding Maree’s call, thousands marched in New York City on March 21, 2012, shouting “We want arrests!” and “Justice for Trayvon!”

The petition would get more than two million signatures.

The Palm Beach Post

More: In Muck City, Glades activists argue, Black lives matter

Prominent professional athletes joined the protest movement, donning hoodies and calling for Zimmerman’s arrest and prosecution.

Years later, many of those same athletes would again use their prominence to publicly call for arrests and prosecutions in other high-profile cases of violence against Black Americans.

Two days after the Million Hoodie March, middle and high school students from across South Florida walked out of school to protest what they described as the injustices of the case.

Students would adopt that same tactic six years later to call for gun control measures in the aftermath of the Parkland school shooting.

Trayvon’s killing and the lack of an arrest sparked activism on college campuses just as it did on middle and high school campuses.

Crowd expresses outrage over the aquittal of George Zimmerman outside the courthouse in Sanford, Florida. (July 13)

AP

Students from Florida A&M University, Florida State University and the University of Central Florida formed a group called “Dream Defenders” and marched from Daytona Beach to Sanford.

“We didn’t pick the name ‘Dream Defenders’ for no reason,” Dream Defender Vanessa Baden told WESH-Channel 2, an Orlando TV station. “We understand what ‘defender’ means. We defend justice, we defend our generation, and we defend the world at large.”

Natalie Jackson, an attorney and Sanford native, said Trayvon’s death and the initial lack of an arrest prodded young people to get active.

“It grew a whole new crop of civil rights lawyers, activists, people who want to be civil rights lawyers,” she said. “Every young law student I meet says they want to be a civil rights lawyer, and they all talk about Trayvon.”

One young person prodded to activism by Trayvon’s death was Alexis Carter, then a 28-year-old attorney and adjunct professor at Seminole State College who taught Zimmerman in an introduction to criminal defense class.

Every young law student I meet says they want to be a civil rights lawyer, and they all talk about Trayvon.

Carter, who said Zimmerman was unique in his class in that his questions indicated he saw the judicial system from the point of view of law enforcement, testified at Zimmerman’s trial.

Later, he made an unsuccessful run for state Senate, determined to make changes to the judicial system.

“My involvement in this case really awakened me to what was happening,” Carter said. “Blacks being viewed as second-class citizens. That’s the message the Black community gets. Things need to change.”

Before Zimmerman’s arrest, famed civil rights lawyer Benjamin L. Crump, who represented Trayvon’s family, generated headlines in a bid to put pressure on prosecutors. But Jackson, also part of the legal team that represented Trayvon’s family, said the actual protests in the aftermath of Trayvon’s death were driven by young people who used social media platforms such as Twitter, which had only been around for half a dozen years in 2012.

“We didn’t know much about social media,” Jackson said. “I remember Ben, he was calling it ‘Tweeter.’”

Video: How Black Lives Matter went from a hashtag to the largest movement in US history

Related: Benjamin Crump, lawyer for George Floyd’s family, a familiar name to Florida

Jackson said the young people who got politically active in the aftermath of Trayvon’s death had a different mindset and a different approach from older civil rights figures.

They did not embrace the premise that the onus was on them to make sure their actions weren’t misinterpreted, she said. They did not embrace the idea that young Black people needed to take care not to offend or trigger white people.

“When we’d talk to older people, they’d say, ‘OK, now, we should do this. We can’t do that,’” Jackson said. “Young people would start with, ‘What did Trayvon do wrong?’”

Where have all the mementos, memorials gone?

In the days after Zimmerman killed Trayvon, then-Sanford City Commissioner Velma Williams was in a tight spot, wedged between increasingly angry Black constituents and a city government struggling to respond.

“I was a city official and a citizen in the community who is a mother, a grandmother,” Williams said. “It was really one of the most difficult times of my life.”

Marta Lavandier/AP

Lee, the Sanford police chief, had refused requests for the release of the 911 call Zimmerman made, citing the ongoing investigation. But word had filtered out that the call could clarify what happened on the night of the shooting, and Williams joined the push to get that recording released.

Sanford’s mayor at the time, Jeff Triplett, was the rare white city official with significant Black support, and Williams looked to leverage that backing – gently.

“I would give him an A-plus, to be very frank, given what he could and could not do,” Williams said of Triplett, who died in February 2021. “I think he handled it extremely well. He could not direct the chief to do anything. People were very critical of him. The mayor and I received a lot of threats. The mayor had to relocate his family.”

Every day that brought no arrest, no release of that recording, brought more anger. At Zimmerman. At Lee. At Williams. At Triplett.

“There were a lot of African Americans who were saying he wasn’t doing anything,” Williams said of the mayor. “I tried to tell them what he was trying to do, but they didn’t want to hear it. They were in pain. They said, ‘This is the way it always is.’”

Lee did eventually release the recording, but it only deepened the divide.

Trayvon’s family and Black people heard the teen calling for help. Zimmerman and his backers heard him calling for help.

Even the memorial that sprung up just beyond the gates of the complex where Zimmerman killed Trayvon became a flashpoint of division.

People brought flowers, crosses, sports mementos.

“There was so much stuff coming in, the people who ran the complex called the city to complain and ask that it be removed,” Francis Coleman Oliver recalled.

The memorial was taken down, with Oliver taking possession of all of the mementos and having them sent to the Goldsboro Museum.

DAMON HIGGINS/palmbeachpost.com

They are there still, awaiting the construction of a new facility where some of them will be put on display, said Pasha Baker, the museum’s director.

“I have about 300 pieces archived so we have this story to continue to tell,” Baker said.

In one of the museum’s two buildings on Historic Goldsboro Boulevard, there are paintings of Trayvon Martin along with others of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Just outside one of the buildings, stone markers carry the names of Trayvon and other Black people killed under questionable circumstances.

There are no other memorials to Trayvon anywhere else in Sanford.

Attorney: ‘Black victims are still disbelieved’

Forty-six days. A month and a half.

That’s how long it took for Zimmerman to be arrested and charged with second-degree murder.

By that point, Trayvon’s family had lost all faith in the Sanford Police Department.

For many Black people, that gap – time to line up a legal defense team, time to make public statements on your behalf, time with your friends and family – highlights the difference in the way Black defendants are treated and the way white defendants are treated.

“The guy should have been arrested immediately and prosecuted,” said Mario Hicks, a Black man who owns a restaurant in the Goldsboro community. “Had it been me, I would have been arrested immediately.”

Richard Ryles, a Black West Palm Beach attorney and former City Commission member, said Zimmerman’s treatment – as well as the delayed arrest and prosecution of the men who killed George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery – shows that white people operate with a kind of impunity in the commission of violent acts against Black people.

“In my opinion, I believe that white people have this special franchise in this country that we can never attain,” Ryles said. “To them, we are second-class citizens, and they are empowered to use police when they see us doing something they don’t feel is appropriate.”

Laura Coates, an attorney and CNN legal analyst, said the roots of that notion stretch back deep into the country’s history.

“It speaks to the history of vigilantism and the laws of runaway slaves,” Coates said, noting that some white people who have committed violent acts against Black people are so confident they’ll face no consequences they call law enforcement themselves. “There is this assumption of us vs. them. There is an assumption of entitlement and camaraderie with law enforcement.”

Coates’ book, “Just Pursuit,” describes how Trayvon’s killing impacted her as a Black mother.

“I gave birth to my son the year Trayvon Martin was killed,” Coates wrote. “I nursed my son while watching Trayvon’s mother fight for justice for her own.”

The guy should have been arrested immediately and prosecuted. Had it been me, I would have been arrested immediately.

There was no video of Trayvon’s killing, and Black legal analysts believe that meant law enforcement and prosecutors would need to put stock in the claims of those who say he was a victim.

“Black victims are still disbelieved,” Coates said, adding that she does not believe juries would have convicted the men who killed George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery if there was no video of those murders. “The video no longer provides the exit off-ramps. It requires you to see with your own eyes what actually happened.”

For many older Black Americans, Trayvon wasn’t just a teenager who had been killed. He was a boy who could have been their own, a point made at the time by the nation’s first Black president, Barack Obama.

“When I think about this boy, I think about my own kids, and I think every parent in America should be able to understand why it is absolutely imperative that we investigate every aspect of this,” Obama said. “If I had a son, he would look like Trayvon.”

Those words hit home hard for many Black Americans.

“That moment speaks to seeing the humanity of Blackness, being able to look at others and seeing a human being, someone worthy of love and protection,” Coates said.

Zimmerman verdict: Little surprise, big disappointment

Sybrina Fulton, Trayvon’s mother, just knew.

After sitting through Zimmerman’s trial, she said, she knew he would not be convicted.

So, she left the courtroom before the verdict came in, despite pleas from Tracy Martin and members of their legal team.

“Tracy was still holding out faith in the jury,” Fulton wrote in “Rest in Power.” “They were, after all, a group of mothers, and he hoped they would see Trayvon as their son as much as ours. But the cultures were too different. I had a sinking feeling that they wouldn’t see things like that. After sitting through the trial, I just didn’t believe they would come back with a guilty verdict.”

Fulton’s assessment was correct. The jury found Zimmerman not guilty of second-degree murder.

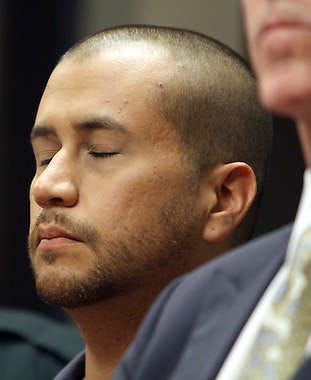

Top: George Zimmerman attends a court hearing in Sanford. (Gary W. Green, Orlando Sentinel | Associated Press) Bottom: George Zimmerman, right, speaks with defense counsel Don West during his trial. (Associated Press)

Left: George Zimmerman attends a court hearing in Sanford. (Gary W. Green, Orlando Sentinel | Associated Press) Right: George Zimmerman, right, speaks with defense counsel Don West during his trial. (Associated Press)

Legal analysts criticized the prosecution team of then-Jacksonville State Attorney Angela Corey – the special prosecutor assigned the case – saying they handled the case poorly and faced a difficult challenge because of Florida’s now-infamous “stand your ground” law.

O’Mara, Zimmerman’s attorney, had been skilled in raising reasonable doubt, describing his client as a man in fear of his life and therefore justified in using deadly force.

He said it had been an uphill climb.

“One of the things we had to overcome was trying to overcome a publicity barrage that could infect our jury pool,” he said.

Previously: Gun bill seeks to repeal Florida’s Stand Your Ground law … again

O’Mara said he has represented many Black criminal defendants and is well aware that implicit bias can hurt their prospects, just as it can help the prospects of white defendants.

Jackson, part of the legal team that advised Trayvon’s family, said O’Mara knew he had a jury of mostly white women and used that to his client’s advantage.

“Mark used race issues and scared this mostly white, female jury,” Jackson said. “I saw him do it at trial. Mark certainly used race. He’s trying to clear his conscience now.”

O’Mara said forensic evidence did not support the notion that Zimmerman pursued Trayvon and killed him.

“There is no support for this chasing after Trayvon,” he said. “Everybody to this day still thinks George Zimmerman jumps out of his car, chased down Trayvon Martin and beat him up.”

Jackson, herself a Black mother, said defense efforts to tar Trayvon in an effort to defend Zimmerman had a broader impact that deepens suspicions of other young Black men.

“Everyone deserves a defense, but you shouldn’t put a target on my child’s back to make your defense,” she said.

‘Progress for the Black man’

Trayvon would be 27 years old now. Still a young man. Married, perhaps. Maybe a father himself.

All of those pathways, those possibilities, were drained away in the moments after he was shot.

His parents started a foundation in his honor. The Trayvon Martin Foundation, based at Florida Memorial University in Miami Gardens, has held peace walks, remembrance dinners, awarded scholarships and hosted summer camps.

Its aim is to raise awareness of the need for criminal justice reform and to help young people.

AP file Photo/Orlando Sentinel, Gary W. Green, Pool

The shot Zimmerman fired into Trayvon’s chest still echoes, but not just for the teen’s family.

It echoes for Zimmerman, too. He remains locked in a sort of mythic struggle with Trayvon.

From 2017: 5 years after Trayvon Martin’s death, what has nation learned?: Column

From 2021: Trayvon Martin’s mother: As BLM turns 8, I reflect on loss of my son, families of movement

By his own choice, Zimmerman has not faded into obscurity.

In 2016, he auctioned off the gun he used to kill Trayvon.

The bidding started at $100,000. CNN reported that the winning bidder may have paid as much as $138,900 for the weapon, though it was unclear if the bidders were real or fake.

“First and foremost, I would like to thank and give glory to God for a successful auction that raised funds for several worthy causes,” Zimmerman said in a blog post.

He had earlier said he would use proceeds from the sale to fight Black Lives Matter violence against law enforcement and oppose what he described as then-presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s “anti-firearm rhetoric.”

The Palm Beach Post

Crump told CNN the auction was repulsive.

“It’s like he is shooting and killing Trayvon all over again four years later with this attempt to auction off this gun like it’s some kind of trophy,” Crump told the network. “I mean, it’s offensive. It’s outrageous, and it’s insulting.”

Three years after the auction, Zimmerman filed suit against Crump, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement and Trayvon’s parents, alleging he was the victim of a conspiracy, malicious prosecution and defamation. He sought $100 million, but the case was dismissed earlier this year.

In 2020, Zimmerman filed suit against Democrats Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg, both of whom were running for president and had tweeted out a happy birthday wish to Trayvon and condemned gun violence, racism, and white supremacy. He sought $265 million in that suit, which was later dismissed.

Neither of the tweets mentioned Zimmerman by name, but he claimed they didn’t have to.

Zimmerman’s suit said, “his name is 100 percent synonymous with Trayvon Martin.”

It’s like he is shooting and killing Trayvon all over again four years later with this attempt to auction off this gun like it’s some kind of trophy. I mean, it’s offensive. It’s outrageous and insulting.

Oliver, the retired teacher who collects artifacts for the Goldsboro Museum, said that, as painful as Trayvon’s death and Zimmerman’s acquittal were, she believes there has been progress over the past decade.

She pointed to the convictions and life sentences handed down to the men who killed Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia.

Up next: Despite ‘startling’ racial statistics, controversial ‘stand your ground’ laws withstand scrutiny

“I think that, over the last 10 years, the killing of Black men has been front and center,” Oliver said. “You can’t just kill a Black man and walk away. Zimmerman may have walked, but, because he did, others can’t. That is progress for the Black man.”

Wayne Washington covers West Palm Beach, Riviera Beach, and racial equity and social justice issues. Follow him on Twitter: @waynewashpbpost. E-mail tips to wwashington@pbpost.com.