In the spring of 1927, photographer Ansel Adams hiked with his friends through the snow at Yosemite National Park in California. The 25-year-old brought along his camera, as he always did, stopping to take a photo he later titled “Monolith, the Face of Half Dome.”

That now-iconic image helped launch his career. Adams went on to become one of the most recognizable faces of American nature photography.

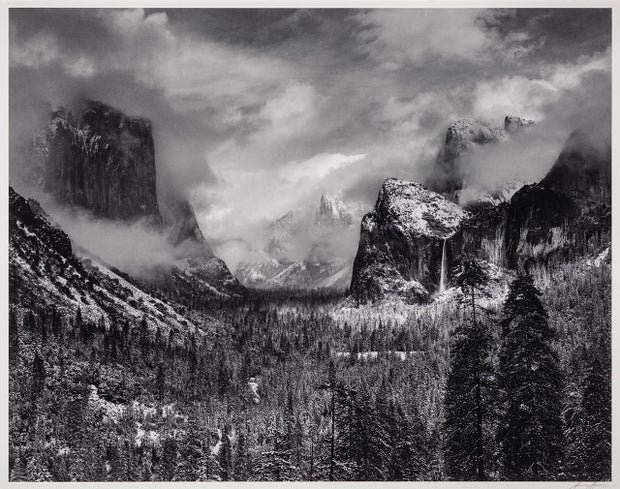

Ansel Adams/Museum of Fine Arts, The Lane Collection

“Many photographers speak about the fact that you cannot take pictures of the Western landscape today, or the national parks, without automatically thinking in some way of Ansel Adams,” said Sarah Mackay, an assistant curator at the de Young Museum in San Francisco.

Adams was born in San Francisco; his first solo exhibition was held at the de Young in 1932. And the de Young is hosting the new exhibition, “Ansel Adams: In Our Time.”

CBS News

Mackay said, “What Ansel Adams advocated for throughout his career was how photography should be considered a fine art in and of itself.”

“For a while, was it not? Were people not taking him seriously?” asked Knighton.

“Yeah, I mean, photography, even into, like, the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s, was always kind of struggling to be considered a fine art medium,” Mackay replied. “Today we know it to be, but it was not even throughout a lot of the 20th century.”

Adams was ahead of his time. In the new exhibition, his images are displayed alongside the works of some of the contemporary photographers he influenced, such as Abelardo Morell, who uses a camera obscura tent to capture two views simultaneously. His picture, “Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of the Yosemite Valley from Tunnel View, Yosemite National Park, 2012,” is actually a photograph of the ground itself with the image projected onto it.

© Abelardo Morell | Edwynn Houk Gallery

“What’s so funny about this picture is, Ansel Adams took ‘Clearing Winter Storm’ from a parking lot,” Mackay said.

“Clearing Winter Storm” is typical of Adams’ work – nature shown as a pristine wilderness.

Ansel Adams/Museum of Fine Arts, The Lane Collection

Contemporary photographers, on the other hand, are more likely to include evidence of a human presence, playing up that contrast. Adams, meanwhile, is best known for the contrasts he created in the darkroom.

When correspondent Ed Bradley visited him at home in Carmel, California for “Sunday Morning” in 1979, Adams gave a glimpse into his painstaking printmaking process:

Adams: “You see how this is burned out? I discard that.”

Bradley: “What do you do with your rejects?”

Adams: “They are destroyed. Everybody asks me, ‘Oh, don’t throw it away. Even if it isn’t good, I’d like it.’ But I can’t have bad prints out.”

Bradley: “You’re a perfectionist now?”

Adams: “Well, you have to be.”

From 1979, photographer Ansel Adams:

Ansel’s son, Michael Adams, used to accompany his father on his photographic expeditions. Today, he lives in that same Carmel home, where he’s kept the darkroom intact.

Ansel Adams was a classically-trained pianist. He referred to the photographic negative as the “score” and the print as the “performance.” Over his career, he “performed” his photos in several different ways, constantly tweaking exposures in the darkroom.

“I would have to say almost all of the ones that are well-known, there’s a fair amount of manipulation in the dark room to bring up what he wanted you to see,” said Michael. “And he would say, ‘This is not what you’re going to see when you look at this, but it’s what I want you to see.”

But as for what he wanted you to see, Adams was reluctant to get specific. Here’s what he told “Sunday Morning” three years before his death: “People say to me, ‘What did you mean with that picture? What did you have in mind?’ I said, ‘It’s in the picture.’ … If isn’t in the photograph, then I failed.”

With crowds still coming out in droves to see his photographs decades later, and with contemporary artists still riffing on his compositions, it’s clear Ansel Adams succeeded in capturing something timeless. Mackay said of Adams, “His ability to spot those images that were going to be majestic, and iconic, and really just gorgeous, is something that I think differentiates him from so many.”

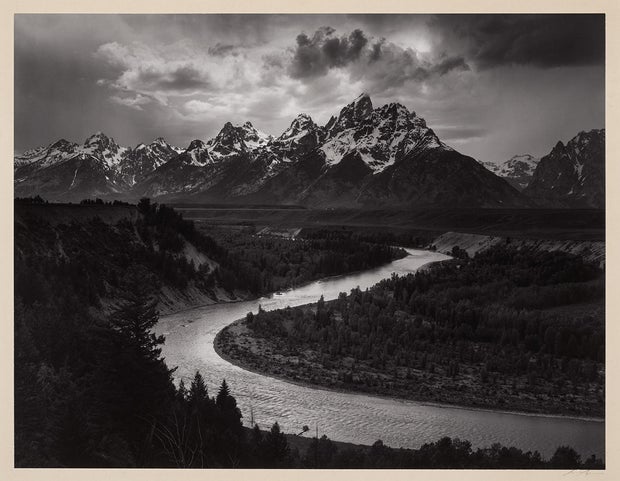

Ansel Adams/Museum of Fine Arts, The Lane Collection

For more info:

Story produced by John Goodwin. Editor: Carol Ross.