CNN

—

After a remarkable series of winter storms, California water officials reported Monday in their April snow survey the Sierra snowpack is among the largest on record, dating back to the 1950s.

The state’s Department of Water Resources surveys mountain snowpack once a month through the winter, and the April survey is usually the most consequential. Officials use the measurement to forecast the state’s water resources for the rest of the year.

Last year’s survey was pitifully low. Water officials had just a small patch of shallow snow to measure after a disappointing winter. The snow depth on April 2 was just 2.5 inches – part of a disastrous multiyear dry spell that triggered water cuts across the state.

But what a difference a year makes.

Twelve months later, the mountains are now loaded with white gold. South of Lake Tahoe at Phillips Station, as snowflakes fell from the surrounding hills, officials measured a snow depth of 126.5 inches and a snow water equivalent – how much liquid water the snow holds – of 54 inches.

Snowpack in the California Sierra is 221% of normal for this location at this time of year, officials at the Department of Water Resources said. Statewide, snowpack is averaging 237% compared to normal for the date – a significant boost after the back-to-back storms.

Sean de Guzman, snow survey manager for the state Department of Water Resources, said this is the “deepest snowpack” he has personally ever measured, noting that there have only been three other years when California snowpack has been greater than 200% of average in April.

“This year is going to join that list and be another year well above 200% of average,” de Guzman told journalists at a briefing Monday. “We still are waiting for more snow data and snow survey results to come in from our various cooperators and partners. But as of this morning, as of right now, it’s looking like this year, statewide snowpack will most likely be either the first- or second-biggest snowpack on record dating back to 1950.”

Snowpack in the Sierra is critical to the state’s water resources. The snow acts as a natural reservoir – melting into rivers and human-made reservoirs through the spring and summer – and accounts for 30% of California’s freshwater supply in an average year.

The state’s largest reservoirs, which were recently at critically low levels, have been replenished and are running higher than their historical averages.

While the heavy rains caused widespread flash flooding and several feet of snow trapped residents in their homes in the higher elevations, the deluge of snow and rain has largely improved California soil moisture and streamflow levels after being gripped by the drought for so long.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom last month also announced the removal of some drought restrictions, while the Department of Water Resources said it will increase the amount of water deliveries to 75% of requested water supplies this year – up from the initial plan of only 5% last year.

“Even though we have this extraordinary snowpack, we know that the droughts are getting deeper and more frequent, and that means we have to use water efficiently no matter what are hydrologic conditions,” Department of Water Resources Director Karla Nemeth said. “And the governor has emphasized that as the path forward for California, and to make sure that we are resilient as an economy and for our environment that we all continue to use water wisely in the state.”

‘Unbelievable’: CNN reporter reacts to record snowfall in California

To find out just how much snow the Sierra Nevada were buried under this winter, Airborne Snow Observatories Inc., which provides its data to California’s Department of Water Resources, flies over the range to gauge what’s fallen.

“We measure snowpack wall-to-wall over mountains from aircraft using lasers and spectrometers,” said Tom Painter, the company’s CEO. “From that information, we can then know the full distribution of how much water there is in a mountain snowpack and also how fast it’s going to melt. That’s allowed us then to change forecast errors from being pretty large to very small and really dramatically changed water management in the west.”

The planes fly for about six hours at a time, collecting different kinds of data through open portals in the belly of their planes, which they process and deliver within about 72 hours to help municipalities allocate water resources, generate hydroelectricity and meet environmental metrics.

“The scanning LIDAR is a fancy laser pointer, essentially, that sprays out laser pulses – about 500,000 pulses per second – flying along at 23,000 feet, and measures how long it takes for the laser pulse to go out, hit the surface and come back,” Painter said. “And we can use that information to then know the surface of the snow. Every square foot of mountain snow is touched by our lasers.”

The scientists then compare this data to when they’ve flown over the same area when there wasn’t any snow.

“The difference between those two is snow depth,” Painter explained. “Depth times density is equal to what’s called snow water equivalent, which is the most important water metric out there that allows civilization to exist in the Western US. It really is the mountain snowpack that drives all of this civilization.”

The year-to-year difference couldn’t be starker, Painter said, adding that this year, there will be snow in the Sierra into the summer.

Last year, the company ended its flyover season in late May; this year, they expect to be flying until August.

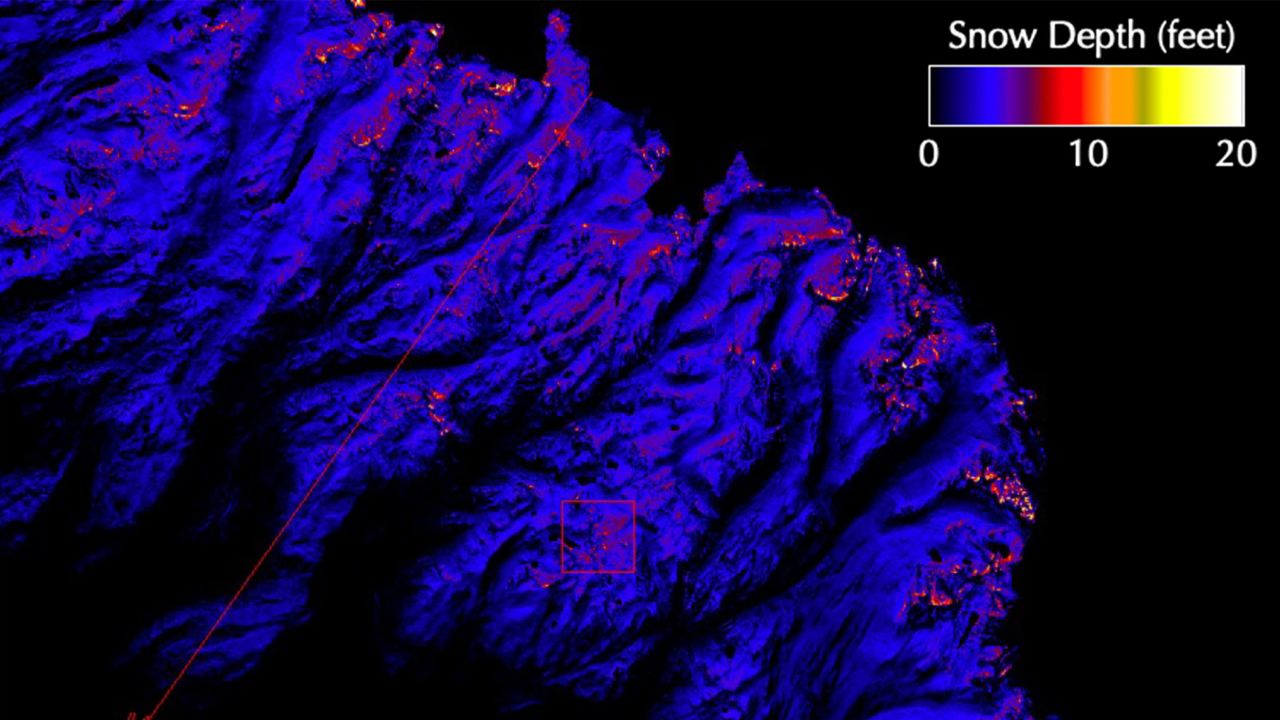

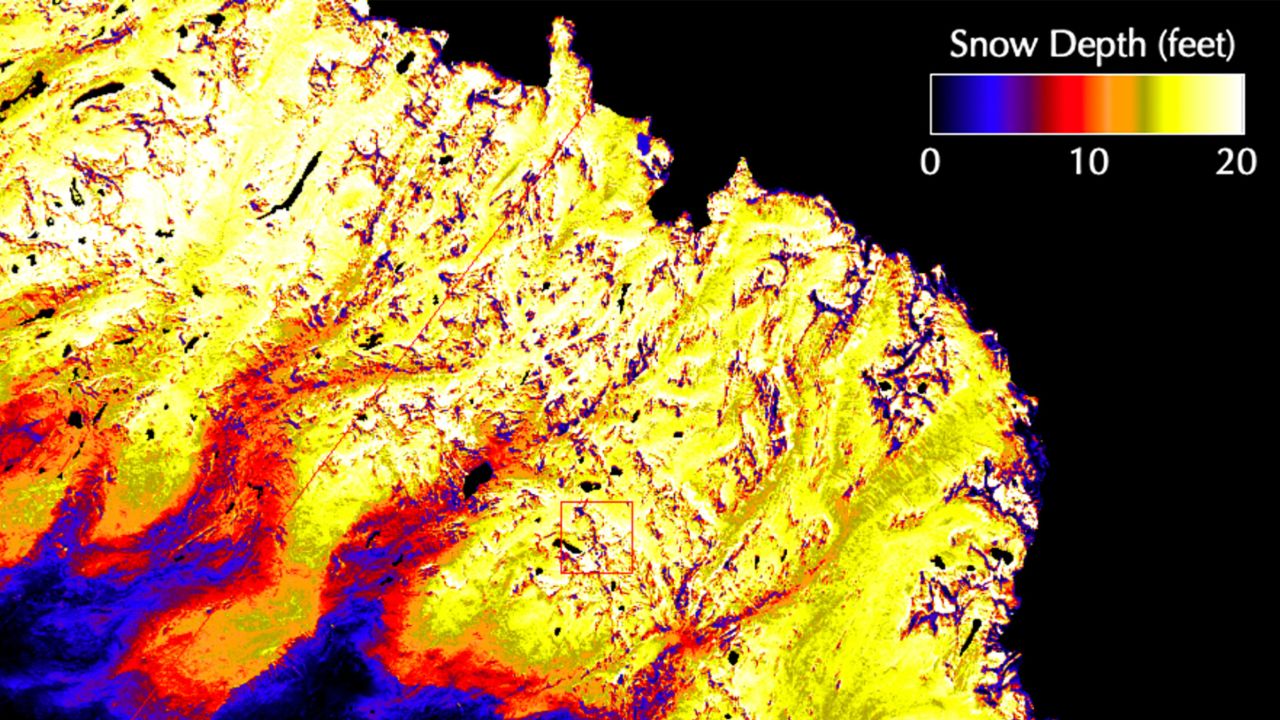

For the Tuolumne River Basin around Yosemite National Park – which supplies water to San Francisco and other Bay Area municipalities – imagery from last year this time is mostly dark blue: barely any snow. This year, the same area is swathed in orange, yellow and white, indicating snow depths of 10 to 20 feet.

On Mammoth Mountain in the eastern Sierra, about 60 feet of snow has fallen this year, breaking the old record set in 2010. And snow depths have reached more than 100 feet in some areas around Mammoth. The amount of snow is so profound that the resort has already announced that the ski season will last through the end of July this year.

“It’s fascinating to look at how the cliffs up on the upper mountain have really gotten buried and the gullies between them are filling in to where they just are kind of disappearing,” Painter noted, adding that he’s never seen Mammoth Mountain this covered.

Despite all the rain and snow that has boosted reservoirs and allowed officials to lift some water restrictions, scientists still say drought concerns are a priority as climate change continues to impact California’s weather.

“The climate models had already been predicting what it is that we are seeing now, which is this hydroclimate whiplash where we’re going from really dry years to really wet years,” Painter said, adding that this whiplash is hard on water managers. “That means we could very well have a dry year next year. No one really knows.”

And as temperatures warm again as summer approaches, experts warn more flood threats lie ahead as the snow melts. California water officials said that after today, they plan to shift their focus “from snowpack building to snowpack melting,” and actively support emergency flood protection efforts.

“We’re now heading into another issue of increasing solar radiation and chances of warm nights and lack of refreeze, and that brings up snowmelt flooding concerns,” said Benjamin Hatchett, researcher at the Desert Research Institute. “That’s going to be something to think about as we move into the spring, summer with this colossal snowpack sitting above us.”

Hatchett also warns not to get “caught up in all these benefits,” and consider what all this water can mean for vegetation growth and wildfire fuel.

“As things start to dry out and get warmer, this is a good year to really think about what’s going to happen, what’s growing, and how can you deal with [the fuels] to reduce your fire risk in upcoming seasons,” Hatchett said.

Even with California’s historic snowpack this year, the state still pulls about a third of its water needs for the southern part of the state from the Colorado River Basin, where the snowfall totals improved this year, but were not as strong as the numbers posted in California.

The country’s largest reservoirs – Lake Powell and Lake Mead – in the Colorado River Basin are still hovering at or near-record-low levels following years of drought and overuse. But it could also improve in the coming months as snowpack levels rise in the region.

“That’s good news for a very strained and stressed system,” Hatchett said. “But we probably need five, six or maybe 10 more years of this to really make a big dent in the situation there, but this is much more encouraging to see.”

In California, water officials will head back to Phillips Station in May to measure more snow. The last time a May snow survey was necessary was in 2020, when the drought began.

The difference between last year and this year in California is significant. And although the state has all this excess of water now, climate experts warn that drought is always looming, especially in a drier, hotter and thirstier world.

Nemeth said there is much more work to be done to prepare and “adapt to our new climate realities.”

“You really get a sense of the extreme nature of our climate here in California,” she said. “There’s lots of fascinating research around the degree to which climate has been driving the intensity of these storms, but also the very rapid shift from very dry to very wet.”

“It is truly an extraordinary moment,” she said. “But we don’t get to stop and enjoy that for too long.”