Some called him “The Scatman.” Others knew him as “Billy Hipp.”

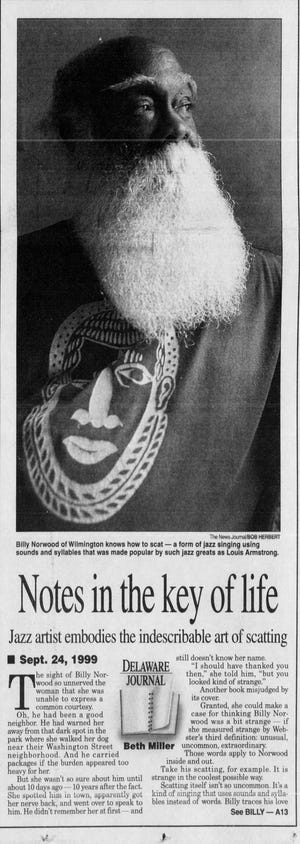

With his iconic white beard, creative scat performances and love of all things music, Marion “Billy” Norwood was a cornerstone of Wilmington’s jazz scene.

Whether through his friendship with the legendary Clifford Brown or his mentorship of contemporary local jazz musicians, Norwood’s impact on his beloved city will continue to be felt for years to come.

“He was a blessing to everybody,” said local jazz trumpeter Gerald Chavis.

Chavis said he was fortunate enough to have Norwood’s help and encouragement as he developed his sound as a musician. Norwood always came to his shows – even last month while in the hospital, Norwood tried to discharge himself to see Chavis perform live.

“He’s the guy that you would try to emulate in life,” Chavis said.

Chavis described Norwood as funny, insightful and “sharp as a tack.” All of Norwood’s lessons – both on life and on jazz – now live inside him.

“Everyone has their own voice,” Norwood told The News Journal in a 1999 interview. “Regardless of how good or bad a person might be in any form of art, there’s something there if you look for it.”

The musician was born and raised in Wilmington’s East Side neighborhood. As a teen, he often tried to sneak into jazz clubs to see performers like John Coltrane and Lionel Hampton play. When that didn’t work, he made a deal with the owner of the Odd Fellows Temple: admittance to shows in exchange for access to groceries made scarce by World War II.

Soon, it would be Norwood up on that stage.

“He was amazing,” said photographer Kenny “Ken-Do” Bond. “I don’t know if there’s a time when I’ve seen anyone else as unique.”

MORE TO READ:Over 20 Christmas concerts, holiday shows in Delaware, including Jimmie Allen

Bond, one of Norwood’s friends, admitted that at first, he didn’t “understand” jazz. That changed the first time he saw Norwood perform, and he quickly “fell in love with it.”

Now, he has a career photographing jazz musicians.

Bond’s relationship with Norwood – much like that of Chavis and other friends – went beyond the music. Norwood would always provide his friends with information, whether it be tales of historic Wilmington over lunch or a stack of DVDs about natural health remedies. His daughter Brooke Alison called him “a walking encyclopedia;” his friends agreed.

“He was such a giver,” Alison said. “And that’s really been instilled in me.”

Alison said her dad incorporated music into all aspects of life. He used to play jazz while the family did chores each Saturday morning, and would do private dance performances for his kids. He even scatted lullabies to lull his children to sleep.

The first time Alison saw her dad perform outside of the house was at former Mayor James Baker’s inauguration in 2001. He “tore the stage up and down,” she remembered, and she found a new appreciation for him as a musician.

She was proud of him then, and she is still proud of him now – even if he happened to keep her up all night practicing his vocal ranges so that he could perform at a moment’s notice.

It was this impressive vocal range coupled with his creativity and passion that made Norwood’s scatting stand out. It also made it a rare form of art.

MORE TO READ:Behind each headstone is a story. This Delaware police officer wants to help remember them

“I don’t know if it can be taught,” Bond said.

The art of scatting is fading, Bond said, much like live music. With the rise of streaming, less people are attending shows in person. This is especially harmful to smaller musicians, and one of the reasons why Norwood made such an effort to attend local artists’ shows.

Before he died in late November, Alison said the Clifford Brown Jazz Festival tried to give her dad an award. He refused, saying that the festival needed to start “putting real jazz musicians back on the menu.”

“He was walking jazz,” Bond said. “He was a walking legend.”

Send story tips or ideas to Hannah Edelman at hedelman@delawareonline.com. For more reporting, follow them on Twitter at @h_edelman.