U.S. District Judge Robert Jonker may have irked the defense during the Gov. Gretchen Whitmer kidnap trials.

He repeatedly cut off defense lawyers, told them to remove the “crap” from their arguments, set time limits on them at one point, refused to let them join an interview with a potentially problematic juror, and scolded them in front of the jury, saying “Start focusing on what the important issues are, before this trial stretches into Thanksgiving.”

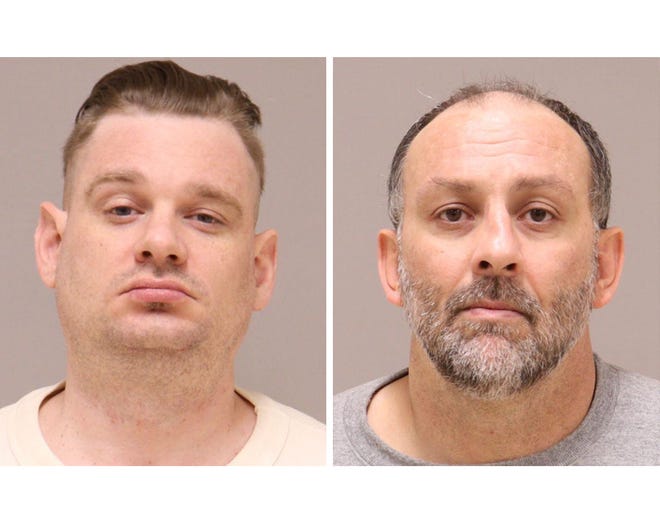

But it’s unlikely any of what the Grand Rapids federal judge did or said will convince an appellate court to order a retrial for Adam Fox and Barry Croft Jr., experts say, noting the defense has a major hurdle ahead: The GOP-heavy U.S. 6th Circuit Court of Appeals.

More:How 3 controversial jurors wound up in the Whitmer kidnap jury box

More:Judge tells Whitmer kidnap jury: It’s not entrapment if you’re already willing

The hill the defense must climb to win an appeal

“The 6th Circuit is a very conservative court … and judges are given a lot of discretion,” said veteran criminal defense attorney Mike Rataj, who took issue with some of Jonker’s rulings in the Whitmer case, but is skeptical about the defendants’ anticipated appeal.

“We’ve all run into judges who are impatient, sometimes rude, sometimes telegraphing to the jury how they want the case to come out,” said Rataj, who has practiced law for 33 years. “But at the end of the day, it’s hard to present those issues to an appellate court and get them to agree the judge abused his discretion.”

Out of the 16 judges on the 6th Circuit, 10 were appointed by Republican presidents; six by Democrats − though a panel of only three randomly drawn judges hears appeals. The full court hears appeals only upon request − and such requests are rarely granted.

More:Defense blasts judge in Whitmer kidnap retrial: You’re favoring the feds in front of jury

More:Juror’s daughter-in-law got high with kidnap defendant Fox near Whitmer cottage

Jonker − whose handling of the Whitmer case is expected to be scrutinized on appeal − was appointed by President George W. Bush in 2007.

Rataj noted that while he did not attend the Whitmer trial, he took issue with some of the judge’s rulings, such as enforcing time limits only on the defense − a rule that only lasted one day − and refusing to let either side participate in the inquiry of a potentially rogue juror. But whether that amounted to a due process violation, or prevented the defendants from getting a fair trial “is a completely different issue,” he said.

“Knowing what I know about the chances for success in the 6th Circuit, I’m not very optimistic for the defense lawyers,” Rataj said. “But they’re doing to do what they’re going to do. They were zealous advocates, and will continue to be zealous advocates for their clients.”

Attorneys for Fox and Croft Jr. have vowed a vigorous appeal. Their clients are facing up to life in prison after a jury convicted them last month of kidnapping conspiracy and conspiring to use weapons of mass destruction. Their first trial in April ended in a hung jury.

On retrial, prosecutors convinced the jury that Fox and Croft were part of a violent militia that plotted to kidnap Whitmer out of anger over her handling of the pandemic and blow up a bridge near her home to slow down law enforcement during the kidnapping. Fox and Croft are among six defendants charged in the federal case. Two cut deals and pleaded guilty early on. Two others were acquitted in the spring trial. Others face charges in a state case.

The defense has long argued that this was an entrapment case, maintaining rogue FBI agents and informants set up unsophisticated big talkers who were merely blowing off steam while the FBI hatched a kidnapping plan and framed them for it.

While the jury didn’t buy that argument, the defense maintains the judge’s rulings prevented them from telling the full entrapment story.

Former Assistant U.S. Attorney Mark Chutkow isn’t convinced that argument will hold up on appeal.

“Mistakes inevitably happen in any high-profile trial, so the defense probably has some issues it can raise on appeal,” Chutkow said. “But the appellate court isn’t going to play armchair quarterback and second-guess the judge’s decisions unless they’re truly consequential.”

Chutkow believes the prosecution had a strong case and executed a more finely-tuned trial strategy on the second go-around, though he does see some potential issues the defense can raise on appeal.

While an appeal won’t be filed until after the defendants are sentenced in December, here are the issues that are likely to be raised before the appeals court:

∎ Jonker’s time-limit order. After repeatedly venting that the defense was taking too long with witnesses and exhausting jurors in the process, the judge mandated that the defense take only as much time questioning witnesses as the prosecution. The time limit was enforced near the end of trial and only affected one witness: codefendant Kaleb Franks, who pleaded guilty early on and testified against the others at trial. The defense argued the time limit was unconstitutional and violated defendants’ right to confront their accuser and ask all the relevant questions. The defense also argued that it needed more time to question Franks on numerous issues, including his criminal record and plea deal, but that the time limit unlawfully and unfairly hampered those efforts.

∎ Jonker’s handling of an alleged rogue juror. On the second day of trial, the defense got a tip that one of the jurors allegedly told a co-worker that if picked to be on the Whitmer kidnap jury, he/she would make sure the defendants would be found guilty. The tip, however, came in from a secondhand source − not the actual worker who allegedly heard this − a person refused to be identified or come forward. The judge interviewed the juror about the allegation, the juror denied ever making such a statement, and the co-worker to whom he allegedly made the comment never came forward. The judge believed the juror and kept the juror on the panel. At issue for the defense is that the judge did not let the defense sit in on the interview with the juror, though the judge did provide the defense and prosecution of a transcript of the interview, which included two court staffers.

∎ Jonker’s hearsay rulings. The defense argues it was unfairly denied an opportunity to introduce at trial various statements that the defendants made with undercover FBI informants, and, statements that certain undercover FBI agents and informants made to the defendants while they were spying on them. The defense argued these statements could help prove the entrapment claim. but the judge ruled that the statements were hearsay, and therefore not admissible, as some of the FBI agents and informants at issue did not testify at trial. Rather, the prosecution opted to try the case without them. So the judge said their statements could not be brought in.

The defense also plans to raise on appeal all the statements it wanted jurors to hear, but the judge said no to all of them.

For example, jurors were not allowed to hear about the misdeeds of FBI informants and agents who were kicked off the case over various misconduct issues, including one agent who assaulted his wife at a swinger’s party.

They also were not allowed to know about an FBI agent’s side business that he ran while investigating the Whitmer case. The defense had argued that the agent had a stake in the outcome of the Whitmer case, alleging he was using it to drum up business for his private security firm. The defense wanted jurors to know that information – but Jonker said no.

The defense explodes

Tensions between the defense and the judge escalated throughout the trial, climaxing near the end, when a defense attorney accused Jonker of favoring the prosecution.

Jonker had just imposed his time limits on the defense. And attorney Joshua Blanchard had had enough.

“It’s creating a perception of how this case ends,” Blanchard argued in court as he accused the judge of playing favorites. “He referred to our questions as ‘crap.’ ”

Jonker, however, defended his actions from the bench, and held that his “most dyspeptic” remarks at trial were directed at a prosecutor, whom he had lambasted a day earlier in front of the jury over an exhibit he wanted to present. The judge accused the prosecutor of being ill-prepared and wasting his time, waving papers in the air as he scolded the prosecutor.

Judge’s comments could prove problematic

For prominent criminal defense attorney Bill Swor, who represented the lead defendant in the government’s failed Hutaree militia trial a decade ago, Jonker’s cutting off of the defense lawyers may be among the strongest arguments on appeal.

If the judge showed a bias against the defense and conveyed that to the jury through his interruptions − as the defense has claimed happened − “that likely would be problematic for an appeals court,” Swor said.

During trial, Jonker repeatedly interrupted the defense lawyers as they questioned witnesses and urged them to “move on” and focus on something else – which they believe signaled to the jury that he didn’t buy their arguments and that they shouldn’t believe them, either.

“If the defense attorney is asking questions of a witness … and the judge says ‘Let’s stop wasting time,‘ that’s a clear signal to the jury that it’s a waste of time and that they shouldn’t pay attention,” Swor said, stressing: “We worry about the court demonstrating bias.”

Swor noted that while judges announce during jury instructions that they “have no opinion,” it “rings hollow” when they make statements like “let’s stop wasting time” when a defense lawyer is making an argument that it believes is important to the defendant’s fate.

That’s what the defense alleges happened repeatedly in the Whitmer trial, though Swor noted that proving the judge crossed a line will be difficult.

“They got a pretty high burden that the judge abused his discretion,” Swor said, adding it will all come down to what the judge actually said, and how often.

Secret tipster could change things

Chutkow, who was the lead prosecutor in the successful 2013 public corruption prosecution of former Detroit Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, believes the potentially problematic juror will raise these questions for the appeals court: What was the content of the allegation against the juror, how serious was the alleged bias and how credible was the source?

Chutkow said the prosecution likely would argue that the judge took prompt action on learning of the allegation: He questioned the juror about the veracity of the claim and whether the juror could remain fair and impartial, and concluded that the allegation wasn’t serious or credible enough to warrant a more formal hearing. The juror denied making the statements. The co-worker he allegedly made them to never came forward.

This, however, could change, Chutkow noted.

“If they come forward now in light of all the publicity surrounding the issue, the defendants might request that the judge conduct a new hearing to get to the bottom of the matter and order a new trial if the claims are substantiated,” Chutkow said.

But if that person doesn’t come forward, Chutkow said, the appeals court might conclude that the claims weren’t sufficiently credible or serious enough to warrant a more probing inquiry involving the judge and both sides − in other words, the judge handling it alone was sufficient.

As for the time limits imposed on the defense, Chutkow said it doesn’t appear they were “significant enough to call into question the fairness of the trial,” noting a judge balances a defendant’s right to confront witnesses against the judge’s responsibility to reasonably manage the trial.

“The judge raised concerns on a number of occasions that the defense’s crosses were becoming repetitive, and the relatively brief restrictions he imposed on the cross of a single witness seems like a fairly modest response,” Chutkow said.

‘Nothing is perfect in our system’

Veteran appellate attorney Harold Gurewitz, who has handled numerous cases before the 6th Circuit, said the appeals process is a complex one that involves diligent briefing and careful review by the court − and typically comes down to how a judge handled a case.

“The judge is the umpire who calls the balls and strikes. And that’s often what it’s about − whether or not the judge made the right decision,” said Gurewitz, who believes the time limits and the juror issue in the Whitmer case are “reasonably important issues that ought to be carefully scrutinized.”

But proving that a judge crossed a line or abused his discretion may be a tough feat, Gurewitz noted.

“It certainly doesn’t mean that it’s impossible,” Gurewitz said. “The court system is focused on attempting to do the right thing. Nothing is perfect in our system. “

In the case of the potentially problematic juror, Gurewitz said the judge may have had a good reason for interviewing the juror on his own.

“I think judges have some basis for saying they don’t want to intimidate jurors by a confrontational setting,” Gurewitz said, noting, “it’s unfair to both sides.”

Gurewitz also said that while certain issues may appear to be strong appellate arguments, the court could conclude that a mistake was made but that the mistake would not have changed the outcome of the trial.

“There are rules like ‘harmless error’ that come into play,” Gurewitz said.

For example, Gurewitz, who handled Kilpatrick’s appeal to the 6th Circuit, argued − among other things − that one of the FBI agents should not have been allowed to offer his opinion about an issue at trial. The appeals court concluded, however, that the agent’s testimony was a harmless error, and upheld Kilpatrick’s conviction.

As Gurewitz has witnessed, it’s difficult to convince a court to change “what has already happened.”

Contact Tresa Baldas: tbaldas@freepress.com